|

|

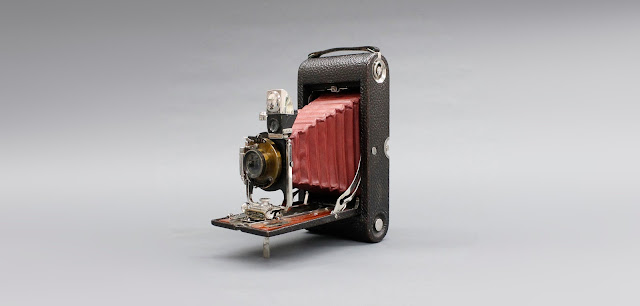

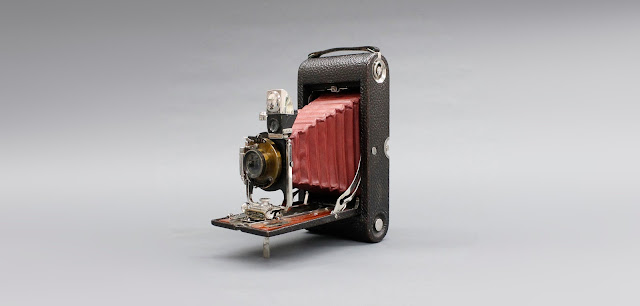

Folding Pocket Camera No. 3A, 1903-1914

Eastman Kodak Co.; Rochester, New York

Metal, glass, wood, and leather; 9 ½ x 4 ¾ x 1 ¾

40633

Gift of Mr. Gurdon Wattles

|

Expedition Prep.

The Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition (1914-1917) stands to date as one of the greatest survival tales of all time. Best told in Endurance: The Antarctic Legacy of Sir Ernest Shackleton and Frank Hurley, coming to call at the Bowers Museum this Saturday, September 30, the Collections Blog embarks this week on a two-part series on Frank Hurley, the expedition’s photographer. The Endurancecrew’s epic story of survival after the shipwreck of their Antarctic-bound vessel would have been unbelievable without his poignant visual storytelling and the great lengths to which he went to document their at-times hopeless journey home. This post introduces Hurley and examines the only camera he retained when the crew had to discard down to the essentials.

Southward

|

Photograph of Frank Hurley taken at the

onset of the Endurance's Expedition. |

James Francis Hurley was born in Sydney, Australia in 1885. Tough as nails from the start, he ran away from home to work in a steel mill at the age of 13. He was a quick study, rapidly learning the finer details of photography and an array of other skills which would prove invaluable on the Antarctic expeditions he gravitated towards. His first expedition southward, the Australasian Antarctic Expedition(1911-1914), earned him a reputation as an immensely tenacious documentarian. It has been suggested that The Home of the Blizzard (1914), the expedition’s official film, is the reason the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition was funded despite the precarious climate of rising war tensions. Hurley was so in-demand that he was the only crewmember other than Shackleton who did not have to interview for his position, and was paid in expedition shares.

The Prince

“With cheerful Australian profanity [Hurley] perambulates alone aloft & everywhere, in the most dangerous & slippery places he can find, content & happy at all times but cursing so if he can get a good or novel picture” —Frank Worsley

True to his character, aboard the Endurance and throughout the expedition Hurley remained honest to a fault. He was aware of how capable he was in comparison to much of the crew and did nothing to keep it to himself. This peculiar attitude and vulnerability to praise earned himself the conspicuous title, “the Prince.” If not for his incredible work ethic and improvisational engineering background leading to several useful and lifesaving devices, it’s difficult to say whether he would have been well liked. Fortunately for Hurley, all aboard understood how important his photographic work was to the expedition’s financial success. Hurley was described by his wayward companions as “a warrior with a camera;” a man who would do most anything to acquire the best possible photograph. His own photographic record proves that he regularly hauled around 40 pounds of equipment to the Endurance’s mast to take otherwise impossible photographs.

|

Alternate view of 40633. This is the same

model used by Hurley to photograph on

Elephant Island. With film, even after 100

years it is still functioning.

|

Snow Blind

Hurley’s photographs were initially documented through the means of his large-framed still and movie film cameras. However, following the loss of the Endurance– the denouement of the dramatic journey—the burden of hauling the heavy equipment became too cumbersome, and so Shackleton ordered that the heavy gear and around 400 of the glass plate negatives Hurley had salvaged from the ice-ruined Endurance be destroyed to save the photographer a second’s hesitation.

FPK No. 3A

Debate with Shackleton, at which Hurley was unsurprisingly an expert, allowed Hurley to save his Folding Pocket Kodak No. 3A and three rolls of film. Produced by the Eastman Kodak Co. between 1903 and 1915, the FPK No. 3A was a folding bed camera which took 3 ¼ x 5 ½ inch postcard format exposures on Kodak 122 roll film. Measuring 9 ½ tall, the camera was designed to be able to fit inside a top-coat pocket, hence the name “Pocket Kodak.” Though even in the 1910s Kodak and other camera companies were producing smaller cameras, its size was likely one of the points factoring in its retention. It’s shell-like design also worked favorably in the harsh Antarctic conditions. Its delicate wood inlay, deep red leather bellow, and mechanical inner workings were encased in heavy, seal grain leather. Hurley himself saw the camera as no replacement for his professional gear though, lamenting “if only I had my cameras.” He took fewer than 40 photographs on Elephant Island awaiting Shackleton’s return with the listless crew.

|

| Advertisement for the FPK No. 3A, digitized by Duke University Libraries. |

Text and images may be under copyright. Please contact Collection Department for permission to use. Information subject to change upon further research.

Comments