|

Sand and Trees, c. 1950

Ralph Love (American, 1907-1992)

Oil on canvas; 20 x 24 in.

2010.5.1

Vernon & Carolyn R. Cunningham Family Trust |

Saving the Everest for Last

Just this week the Bowers Museum opened Everest: Ascent to Glory, an exhibition organized in collaboration with the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG) and curated by the award-winning author Wade Davis which looks at the history of the earliest attempts to climb the highest mountain on earth: Mount Everest. With our research distilled into labels and panels, what better chance to take our mountainous momentum and explore peaks and pinnacles as they are featured in a selection of art from the Bowers’ permanent collection? This post explores both the importance mountains in art and as sacred spaces.

|

Vase, early 20th Century

China

Porcelain; 5 7/8 x 2 1/8 in.

2010.6.22.2

Gift of the Estate of Mrs. Margaret Paul |

|

Incense Burner (Boshalu), Han Dynasty (206 BCE - 220 CE)

China

Ceramic and glaze; 6 1/2 × 7 9/16 in.

97.2.1a,b

Gift of The Chang Foundation |

|

Carved Tusk, early 20th Century

China

Carved ivory; 12 x 30 in.

88.31.20

Gift of the City of Los Angeles Department of Recreation and Parks |

Mist Opportunities

Likely due to the rugged topography of the nation, mountains—be they symbolically significant or solely present for composition—feature heavily in Chinese art. This early 20th century vase is decorated with a generic landscape with mountains disappearing into the horizon. Those who have seen Everest: Ascent to Glory may draw parallels between the model of Everest in the exhibition and the much smaller peaks on the lid of this incense burner. The jagged spires of the lid represent one of the four sacred Taoist Mountains, all of which are the sites of Taoist monasteries and shrines. Smoke from the burning incense inside the vessel would have looked like clouds gathered around the peak. Finally, an elaborate scene is carved from this solid ivory tusk. As is often the case in Chinese depictions, mountaintops rise through the clouds, creating a perfect scene for the charming folk tale it depicts.

|

Mt. Fuji from Kamakura, 1920-1922

Evylena Nunn Miller (American, 1888-1966); Japan

Oil on beaverboard; 10 x 14 in.

31804.10

Evylena Nunn Miller Memorial Collection |

Fujisan

Mount Fuji, featured in this painting by Evylena Nunn Miller, is among the most famous mountains in the world. It is without a doubt the most famous in Japan, historically making it a common subject for ukiyo-e woodblock prints, porcelains, and much later western travel paintings. Just years after the Great War ended, Miller started a world tour that she paused to spend time teaching in Japan. Her travels there took her from north to south, but like generations before her, she gravitated towards Fuji’s snow-capped cone on several occasions. Just as the Taoist mountains discussed above are hallowed ground, Mount Fuji or Fujisan is also revered, earning its place in Japanese Shintoism even prior to the advent of written records. In Shintoism, the mountain is anthropomorphized as a divine being named Konohanasakuya-hime and depicted as a beautiful woman.

|

South Lake Sierra, c. 1935

Edgar Alwin Payne (American, 1883-1947)

Oil on canvas; 30 × 25 in.

2012.5.1

Gift of Mr. Donald A. Honer |

Painting the Divide

Peaks are features of more Bowers paintings than can be counted, but very often as background elements. Even in Miller’s painting of Fuji where a third of the canvas by area is dominated by the mountain, the same peak barely appears for the midday haze. California plein air painters are a rare group that will on occasion invert the natural order of things. Here are two examples of Californian painters committing what is generally considered a compositional no-no, throwing their foregrounds into shadow while bathing distant hills in enough light to draw the viewers eyes directly to them. Elmer Wachtel does this to a lesser extent in an untitled oil painting which is further explored in The Wachtel Watchers: The Earth in Plein Air. Edgar Alwin Payne on the other hand makes no mistake of his intention to emphasize the rock face behind the namesake of South Lake Sierra. He uses dark blues for the lake while beautifully illuminating the windward rock face behind it in a reddish golden light.

|

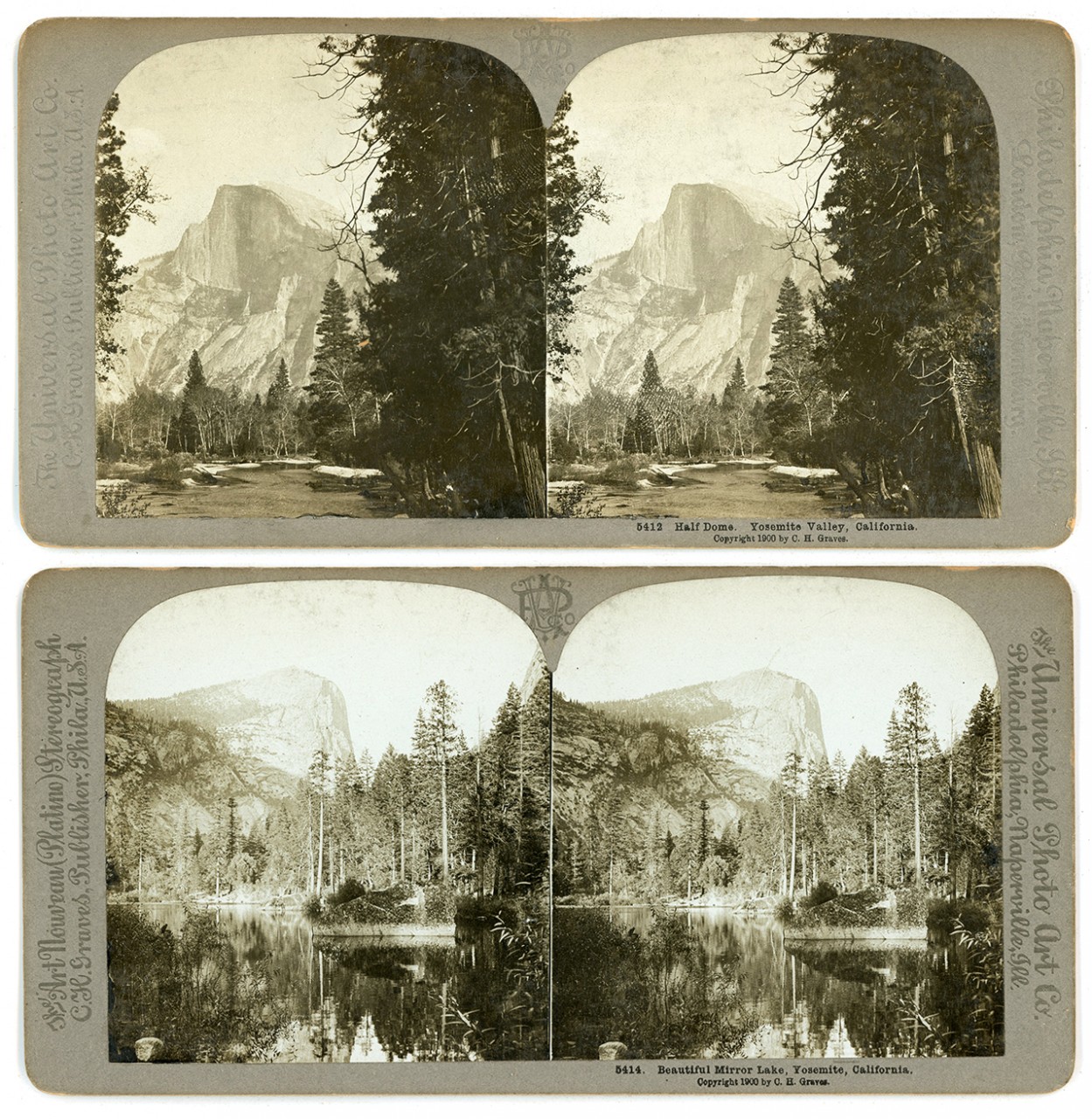

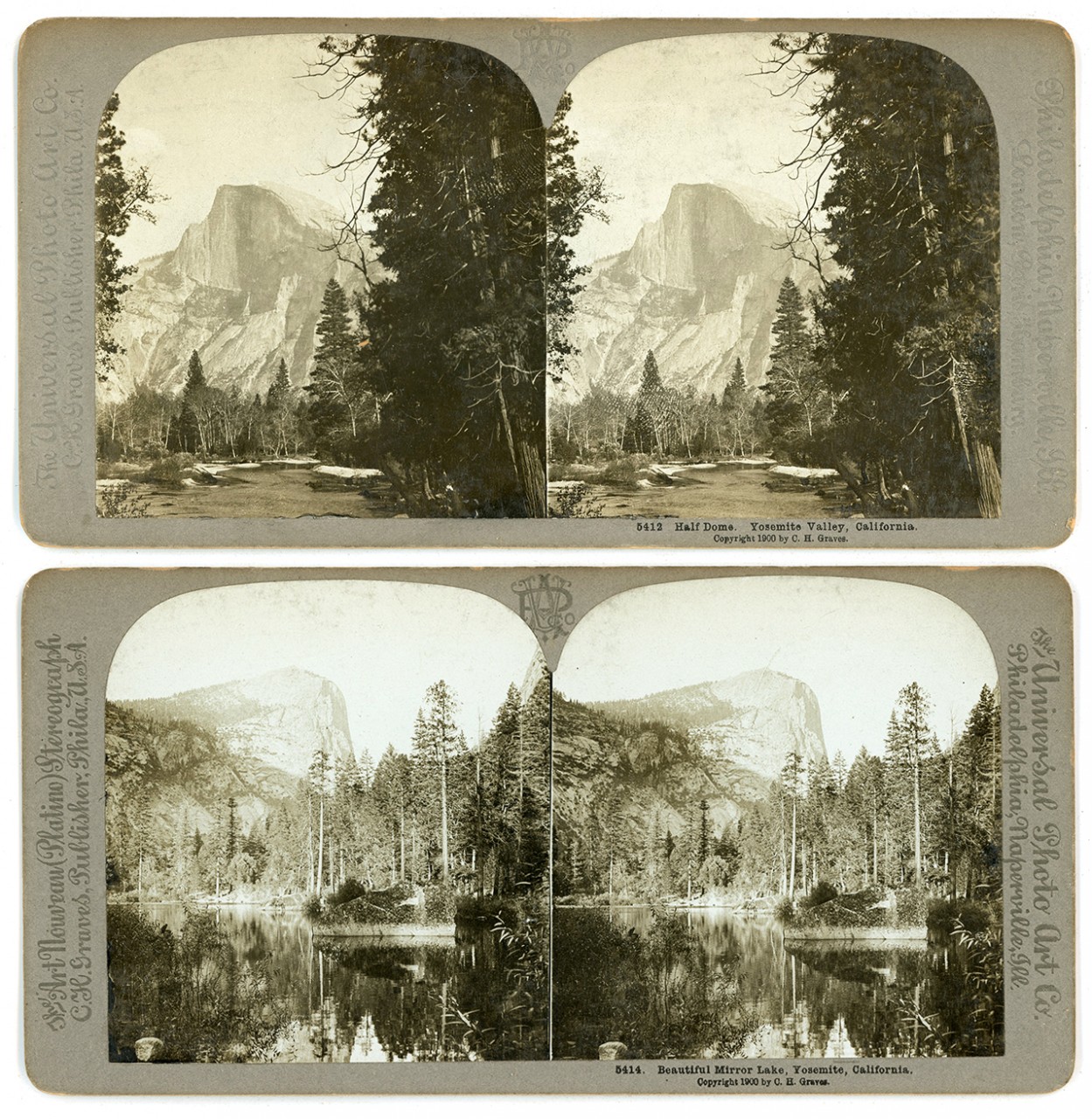

Stereographs of Half Dome and El Capitan, 1900

C. H. Graves (American, 1867-1943); Yosemite, California

Photographic prints

40464.165-.166

Gift of Lt. Richard M. Bradley |

Yo, See Mighty Mountains

Like painting, photography is frequently employed as an artistic medium for capturing mountains. Here we look at stereographs, paired sets of photographs that could be viewed in a stereopticon to achieve an effect now similarly accomplished with the oodles of technology loaded into virtual reality headsets. The mountains that they depict are Half Dome and El Capital in Yosemite, among two of the most iconic climbing faces in the world—coincidentally an accolade that they share with Mount Everest. Like the beyuls surrounding Everest that are sacred in Tibetan Buddhism for the holy relics scattered there by Guru Rinpoche in the 8th century, the valleys of Yosemite created by stark peaks like Half Dome and El Capital are sacred spaces for the Northern Sierra Miwok living there long before Europeans came to California.

Text and images may be under copyright. Please contact Collection Department for permission to use. References are available on request. Information subject to change upon further research.

Comments