|

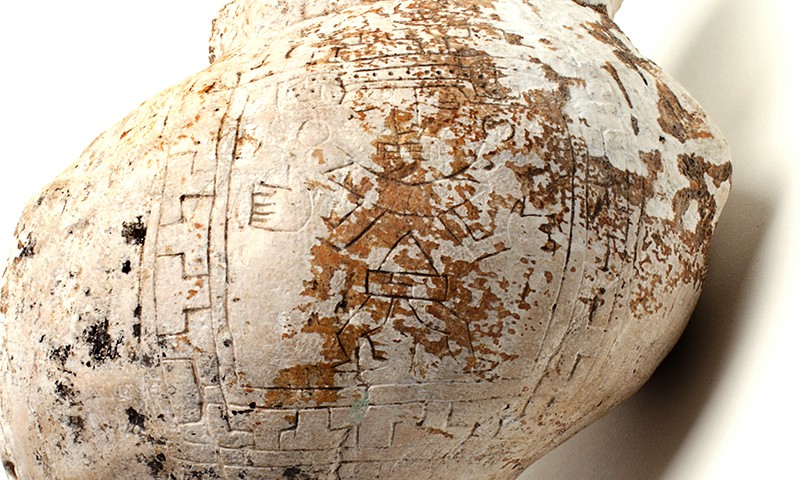

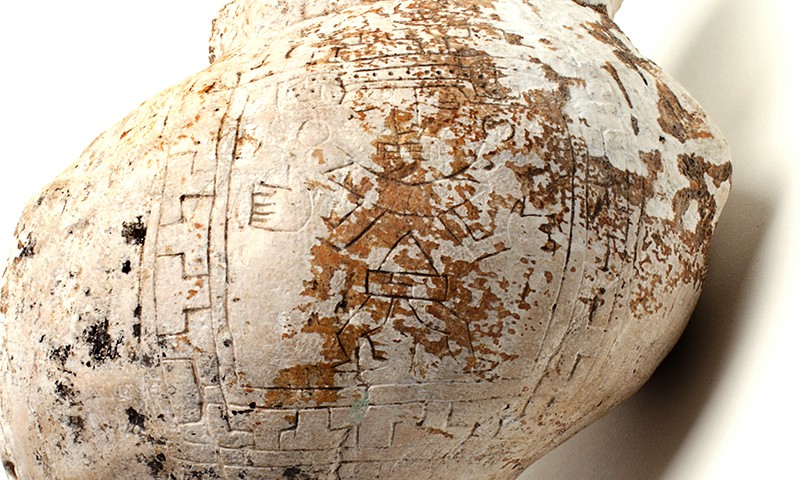

Incised Shell Trumpet, 900-1200

Michoacán culture; Puruándiro, Michoacán, Mexico

Shell; 12 1/2 x 6 3/4 x 5 1/8 in.

34076

Gift of Mr. Graciano Bernal |

Tooting Their Own Horns

Shells take the sea with them wherever they go. Maybe this is the reason why so many cultures utilized and still utilize shell as a medium for both artistic and utilitarian purposes. The Pre-Columbian cultures of Mexico were no different. Here shell was commonly used to make tools like spoons, ladles, buttons, and harpoons, as well as luxury items such as jewelry and other adornments. Shells were also used as musical instruments, horns in particular. Music from these horns was used in religious ceremonies, everyday festivals, and dances. This post will explore various instances of shell art from Pre-Columbian western Mexico, how they were made, how they may have been used, and their cultural significance.

|

Shell Pendant, 1200-1500

Mexico

Shell; 3 1/4 x 6 7/8 x 1 1/2 in.

85.26.38

Gift of Peter G. Wray |

Whorls in the Workshop

In order to manufacture the musical instruments, very few structural changes were made to the shell itself. The tip was cut off and the edges of the newly made hole were rounded so that the musician could blow into it. Different holes were drilled into the end of these shells through which carrying straps could be threaded. These shell horns were often engraved or incised with geometric, zoomorphic, and anthropomorphic designs, as can be seen in the figural carvings etched into the Bowers Museum’s white, striated shell. Despite its apparent similarities to this shell, the piece with the skull engraving was not a horn at all. It was cut in half, rendering it unable to produce sound. This may indicate that it was used as a pendant instead of a musical instrument.

|

| Detail of 34076 |

Chambers within Chambers

For archaeologists, these shell horns tell more about ancient indigenous Central Americans than just how they made music. The excavation of a shaft tomb at Las Cebollas in Jalisco, off the coast of western Mexico, yielded no less than 125 conch shell horns. This indicates that these objects held tremendous importance to the culture at large or the individual with whom they were buried. Upon analyzing these horns, it was discovered that several different species were represented among them, some of which came from as far away as the Gulf Coast of Mexico. This suggests the presence of large scale trade and cultural contact and exchange between the western and eastern Mexican coasts.

|

| Depiction of Quetzalcoatl wearing an ehecailacocozcatl from the Codex Magliabechiano, mid 16th Century |

Music in the Air

Shells and shell horns also held divine significance throughout Mexico. The conch shell is a symbol commonly associated with the feathered serpent and god of the wind, Quetzalcoatl, who came to be worshipped all throughout Mexico. Shells were often carved into the likeness of an ehecailacocozcatl—a “Wind Jewel” which the god is often depicted wearing as an ornament. Music also has a connection with the wind within the cultural consciousness of Pre-Columbian Mexico. A myth attributed to the Aztecs describes the god of the four quarters of heaven coming down to Earth and seeing that it is silent. Saddened by this, he calls to his brother, Quetzalcoatl, who goes to the house of Father Sun where all the musicians and singers live. Quetzalcoatl scoops them all up and spreads them around the Earth, where they taught the people how to make music, which was a source of happiness for the people.

|

Trumpet in the Shape of a Shell, 200 BC-300 AD

West Mexico Shaft Tomb culture; Colima, West Mexico

Ceramic; 6 x 8 3/8 x 15 1/2 in.

86.55.34

Gift of Maryanne H. Wray Aeed |

A Dead Man’s Party

As previously noted, the Pre-Columbian inhabitants of Mexico took these shell horns with them to the afterlife, but not always in their organic form. Many of these ‘shell trumpets’ were actually made from ceramic. They were created to very similar specifications as their organic counterparts, including the mouthpiece shaping, so that the dead could bring their music with them into the afterlife. The blackening around the mouthpiece of this ceramic shell could also indicate use, so perhaps these ceramic objects held significance in life as well as in death. The creation of effigies out of ceramic was a very common practice which was not at all limited to shells. Veritable zoos of animals and workshops-worth of tools were placed in shaft tombs to accompany the deceased after death; these could all be made from ceramic. A great example of these tomb effigies can be found in the Bowers’ Ceramics of Western Mexico exhibit. The ceramic dogs on display were part of this same practice of creating items to accompany the dead into the afterlife. It goes to show that a love of music and their dogs transcends culture and time.

Guest authored by Elizabeth Kriebel, Intern for the Bowers Museum's Collections Department. Text and images may be under copyright. Please contact Collection Department for permission to use. References are available on request. Information subject to change upon further research.

Comments