|

Modified detail of F81.109.8

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Reilly P. Rhodes in Memory of Clarence H. Hoiles |

History of the Zodiac

This past Sunday marked the beginning of the Lunar New Year, a holiday closely tied to the zodiac observed by cultures of eastern Asian countries like China and Vietnam as well as their diaspora. The Chinese zodiac of twelve animals appears to have originated as far back as China’s Shang dynasty (1500-1050 BCE), perhaps through the worship of zodiac’s animals. When paired with the secondary elemental cycle of wood, fire, earth, metal, and water, the twelve-year cycle of the zodiac becomes a sexagenary cycle. This new year, 2023, is the Year of the Water Rabbit, and promises to be one full of peace and prosperity, both of which would be welcome thematic changes from the conflict and instability of 2022. Rabbits are found on every continent in the world except for Antarctica, so their depiction is nearly ubiquitous in art from around the globe. As the Bowers Blog did two years ago for the Year of the Ox, this post looks at rabbits in the art of the Bowers’ permanent collections and the general significance of rabbits to the cultures of the artists.

|

Pipe Head, date unknown

Hopewell or Adena culture; Scioto River Valley, Ohio

Claystone; 2 x 3 1/2 in.

96.28.27

Patrick J. Hanratty, Ph.D. |

Plains' Old Pipe

This is a platform effigy pipe from the Scioto River Valley. Up to 2000 years ago, an Indigenous craftsperson of the Adena or Hopewell culture carved this pipe out of a relatively soft claystone found locally. Pipes in this tradition were made from a variety of different soft stones, and with a wide range of effigies including ancestors and many of the animals endemic to the region. The smoking of tobacco was a sacred feature of many ceremonies for Plains cultures. Though much has been lost about the practices of the Adena, these pipes may have held animistic spirits which were brought to life through the act of smoking. As a food source for the Adena people, rabbits would have been held in high regard.

|

Children’s Festival Hat, Qing dynasty (1644-1912)

China

Cotton, silk and fiber; 18 1/2 x 8 1/2 in.

2001.1.39

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Long Shung and Anne Shih |

Cottontail Cap

Qing dynasty children’s hats, of which this is an example, have already been published about in greater depth on the Bowers Blog, but it is important to note that rabbits are among the many styles used for the decoration of these hats. Outwardly endearing, the primary function of these hats was to protect children from evil spirits by fooling the villainous entities into mistaking the wearer for an animal. The image above shows the back of the hat, from which two long rabbit ears extend. In China, rabbits tend to symbolize mercy, elegance, and beauty, with people born in that year being attributed with those characteristics. Many of the animals depicted on these hats are from the Chinese zodiac, but there are exceptions to this such as cat hats. Housecats had not even been introduced to China by the time the zodiac was first being used.

|

Netsuke, 19th to 20th Century

Japan

Ivory and pigments; 1 x 1 3/4 in.

2005.9.26

Gift of Cleo M. Stater |

Bunny Benedictions

Netsuke are small toggles, usually made from ivory, that were used with a cord to hang containers from the belt sashes on traditional Japanese attire. These have been explored in more detail in Potent Portables: History of Japan’s Netsuke. Though animals are already common motifs of netsuke, rabbits are particularly popular in Japan as messengers to the gods and as symbols of good luck. This portable potent portent of fortune may have been part of a netsuke set of the Japanese zodiac—slightly different than the Chinese zodiac—as it was donated alongside almost all of the zodiac’s animals.

|

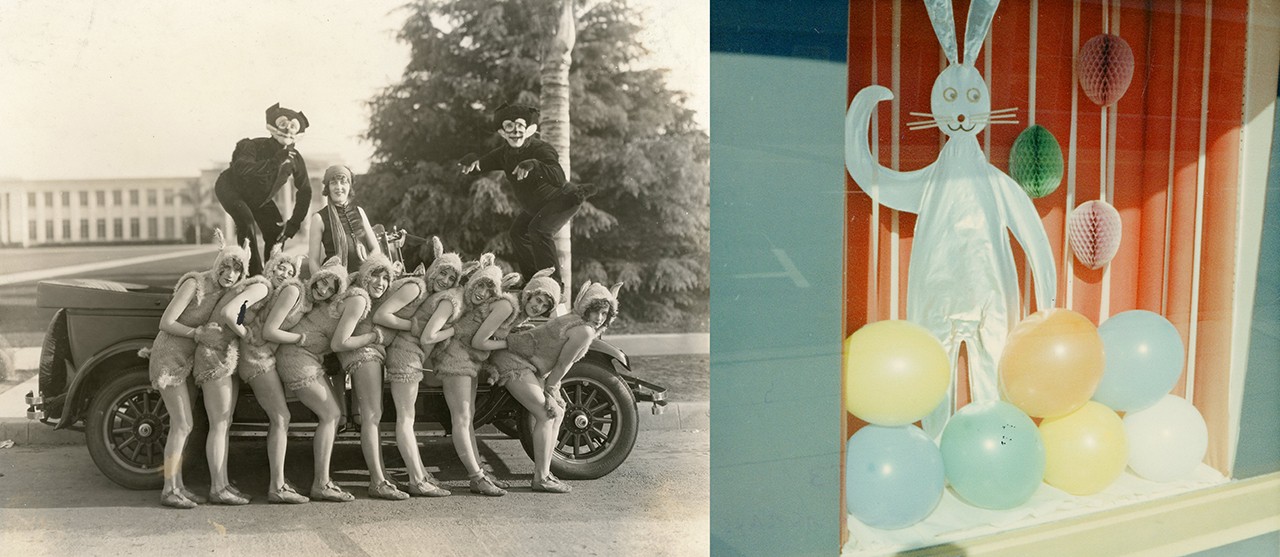

Hare Line and Cat Conspirators, early 20th Century

Leo Tiede (American, 1889-1968); Santa Ana, California

Photographic print; 8 x 10 in.

37827.558

Leo Tiede Photo Collection |

Easter Store Display, 1968

Leo Tiede (American, 1889-1968); Santa Ana, California

Photographic print; 6 1/2 x 5 in.

37827.393

Leo Tiede Photo Collection |

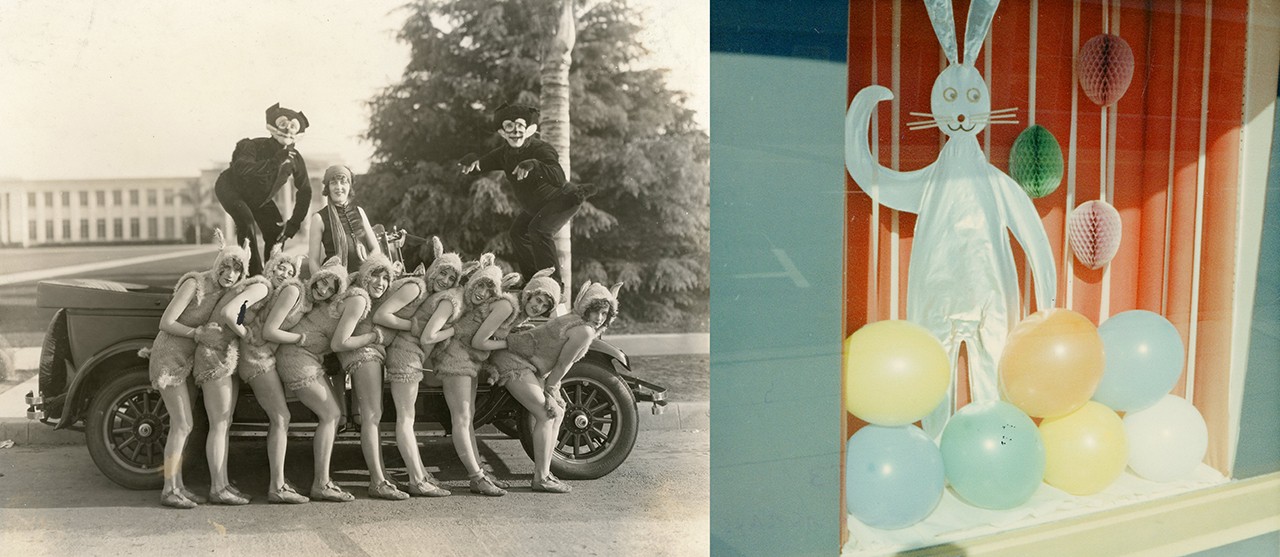

Ambiguous Easter Lore

We could not have a survey of the Bowers permanent collection without a look into the museum’s eclectic offerings of historical photographs from Orange County. Both of the above images are from the 1,700 in the Leo Tiede Photo Collection and are almost certainly related to the most popular North American celebration featuring bunny rabbits: Easter. The image on the right appears to be an unknown Santa Ana store’s Easter display. The image on the left is harder to unpack; the combination of young women dressed as rabbits and young men dressed at cats certainly does not lend itself to any easy answers. In Western cultures, the ability of rabbits to rapidly proliferate has led to their association with spring, fertility, and renewal.

|

Rabbit Effigy, date unknown

Possibly Nayarit, Mexico

Fired clay; 4 1/2 × 3 1/4 × 6 in.

F81.109.8

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Reilly P. Rhodes in Memory of Clarence H. Hoiles |

400 Rabbits

Though this rabbit figure is said to come from Nayarit, Mexico, a lack of similar examples and substantiation from an expert on Mesoamerican art indicates that it may have been made by another Mexican or Central American culture. Somewhat similar spouted vessels have been linked to the Comala style of Colima, as well as the Olmec and Huastec cultures. Hunting rabbits was common in Mesoamerica, and rabbits were also associated with the moon and drinking pulque, an alcoholic drink made from fermented agave sap. The latter link may be the reason that most rabbit effigies from the larger region are spouted.

|

Two Kids, 1967

Lin Yu-shan (Taiwanese, 1907-2004); Taiwan

Ink on paper; 32 × 14 in.

2020.13.1

Gift of Aloysius F. Kuo |

Childlike Innocence

This painting of rabbits was created by Lin Yu-shan, considered a great teacher, artist, and master of contemporary-traditional Chinese flower and animal paintings. Born during the Japanese occupation of Taiwan in 1907, Lin Yu-shan actively studied Chinese poetry and literati painting. It was in Kyoto during the 1930s that he became better acquainted with traditional Chinese painting, as Japanese painters had absorbed and learned many of their techniques from the artists of China’s Song dynasty. Lin Yu-shan was a firm believer in close observations of nature and fused human emotion with his animal subjects. Here even the title suggests that the rabbits are based on human children.

Text and images may be under copyright. Please contact Collection Department for permission to use. References are available on request. Information subject to change upon further research.

Comments