|

Scholar’s Desk, Ming Dynasty style (1368-1644)

China

Wood

L.2013.9.7

Loan Courtesy of Anne and Long Shung Shih |

All Four What

Through the past 2,000 years of Chinese intellectualism, Chinese scholars have been greatly respected for their dedication to the study of philosophy, classical literature, poetry, and the teachings of Confucius. A scholar’s area was meant to be a quiet, private place where one could study such topics and where the fine arts of calligraphy, painting, writing, and music were practiced. The tools and furnishings that were placed on a scholar’s desk were as refined and sophisticated as the intertwined pursuits of writing and calligraphy they were used to practice. Ink, inkstone, brush, and paper were so essential to the scholar they were known as the Four Treasures of the Scholar’s Studio. Here we take closer look at how each of the Four Treasures would have been used, along with other pieces one might find on a Chinese scholar’s desk.

|

Ink Sticks, Qing Dynasty (1644-1912)

China

Ink and paint

2014.14.2.1,3.1

Gift of Anne and Long Shung Shih |

An Inky Clarity

Chinese inks were traditionally produced in the form of sticks which were created in different ways depending on their color. Black stones were made by burning natural materials to produce carbon. The residue of this burnt material was then collected and mixed under controlled conditions with glue made from animal skins or bones. After the mixing process was complete, the compound was heated for many hours and repeatedly pounded. Several different additives could be introduced to the compound at this time, including aromatics. At this point, the compound would be in a paste-like state and could be pressed into molds of various shapes. Designs such as dragons or writing would be carved into molds and were often decorated with gold leaf and paints.

|

Ink Stone, Ming Dynasty (1368-1644)

China

Stone; 1 7/8 × 6 × 4 5/8 in.

2014.14.4

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Danny and Anne Shih |

Ink Stones in the Goldilocks Zone

To be used, ink sticks needed to be mixed with water. Ink stones—not to be confused with the similarly named sticks—were elaborate basins for doing just that, specially designed to be abrasive enough that grinding an ink stick into the floor of its well would cause small pieces of the stick to break off and color the water, but not so abrasive as to damage the tips of calligraphy brushes. While Chinese ink stones were made in a variety of different shapes and sizes and from various materials, ink stones made of stone are considered to possess a higher quality than those made of other materials. Scholars spent considerable time selecting an ink stone for their study as they were among the most prestigious and visible items to sit on their desk.

|

Calligraphy Brush Pot with Brushes, early 21st Century

China

Wood, jade, bamboo, hair, plastic, shell and silk

2014.14.7-.12,.15

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Danny and Anne Shih |

Getting a Brush Grip

As with the other Four Treasures, brushes were used as adornment as much as they were painting. When not in use, brushes were kept in brush pots, on racks, or in boxes. Traditionally, they were made from wood with their tips sourced from animal hair, but bird feathers and human hair were also used. Brushes are considered the ideal tool for calligraphy as the bristles allow a great deal of flexibility. They were held between two sets of fingers: the ring and middle gripped near the tip and the hold was further braced higher on the handle by the thumb and the index. Many factors influence brush strokes, such as the angle of the brush, the viscosity of the paint, various speeds, pressures, and techniques that might be used by an artist, and more.

|

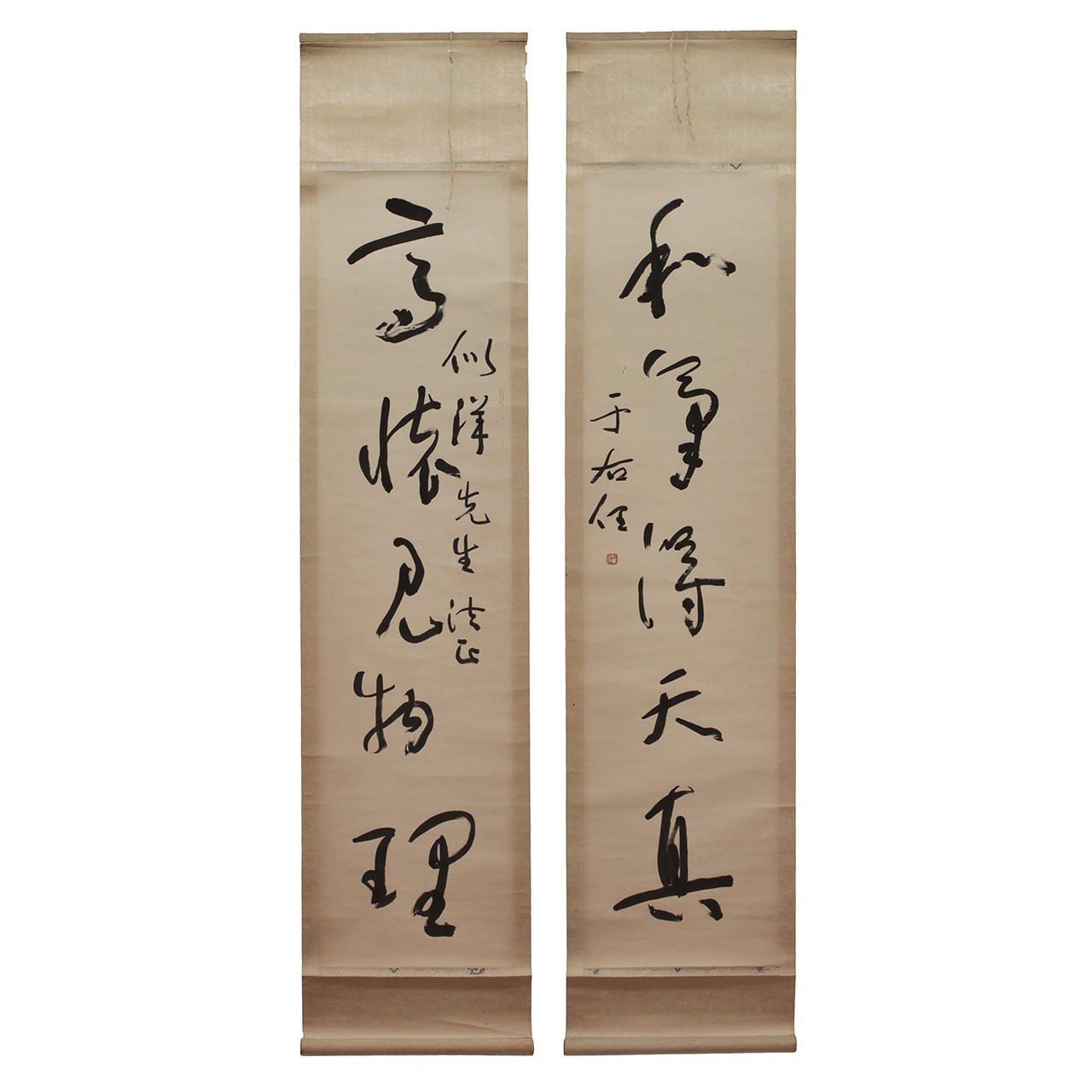

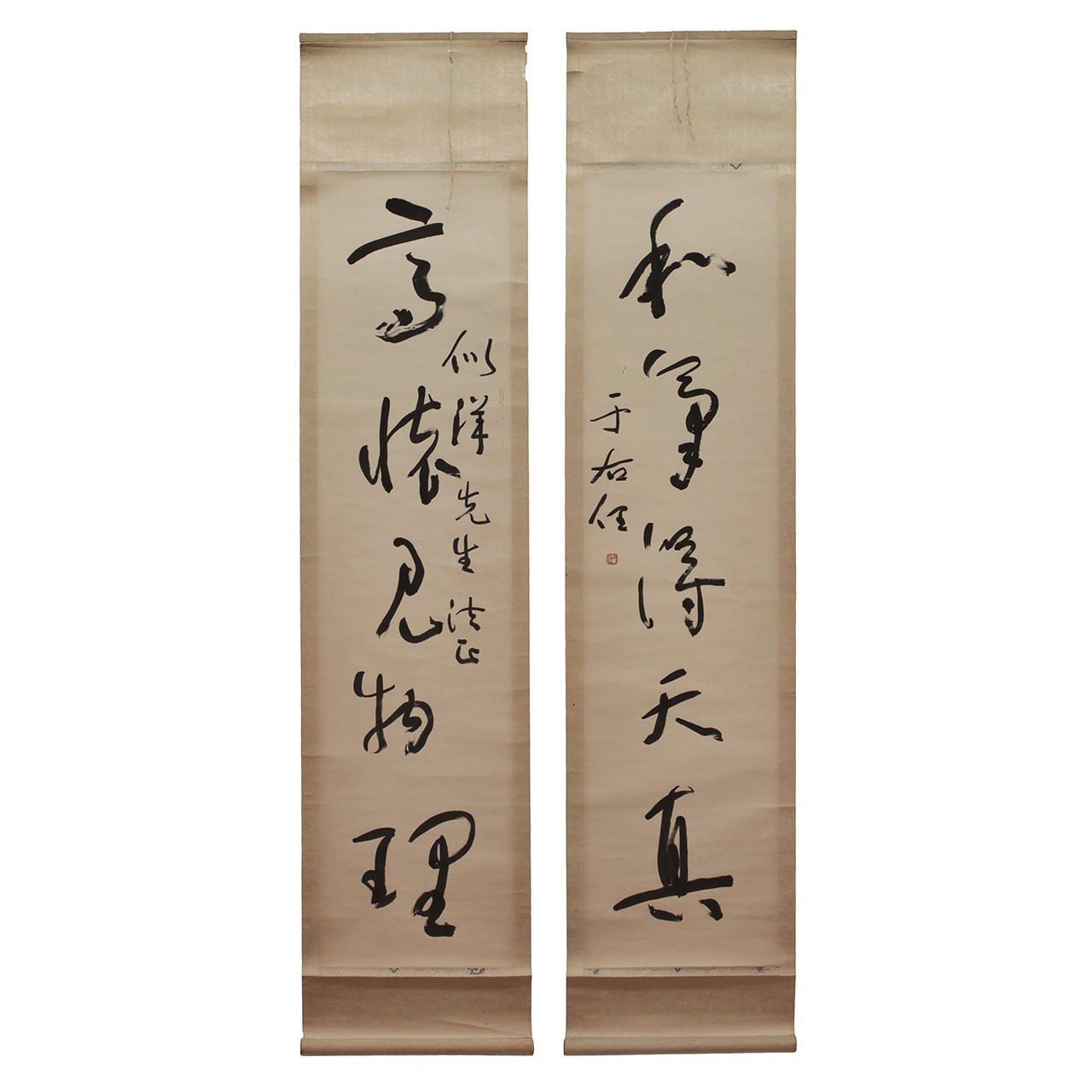

Calligraphy Paintings, c. 1950

Yu Youren (Chinese, 1879-1964); China

Wood, silk, ink on paper; 66 5/8 × 14 3/4 in. (each)

2013.14.1.1-.2

Gift of Ms. Julia Chang Wan |

Infinite Scroll

Paper is the surface on which most Chinese painting and calligraphy was practiced. It was invented in China around 100 CE. Origianally made from rags, it was later produced from bark, hemp, and bamboo. The backdrop to the scholar’s desk on display at the Bowers illustrates just how large Chinese paintings can be. Most, though, were done on long, thin pieces of paper which could be rolled up as scrolls. As such, weights used to keep paper from rolling up were common features of a scholar’s desk. These two scroll paintings on display alongside the scholar’s desk at the Bowers Museum were made by an artist to thank the father of the donor for doing him a kindness. They read: "Only with a peaceful mind can one find the essence of nature" and "Only with high aspirations can one discover the truth of all things."

|

Set of Two Calligraphy Seals, early 21st Century

China

Stone; 3 1/4 × 1 1/8 × 1 1/8 in. each

2014.4.19.1-.2

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Danny and Anne Shih |

Other Desk Toppers

Seals are important components of paintings and calligraphic works but are also seen as art forms themselves. Seals were first used as markers of authenticity on important official government communications, but over time came to be used by artists to mark their works as authentic.

|

Calligraphy Brush Washer, Qing Dynasty (1644-1911)

China

Glass; 3 1/2 × 6 1/2 × 5 1/2 in.

2014.14.14

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Danny and Anne Shih |

Other Desk Toppers

While painting or creating calligraphy, a scholar would use a brush washer filled with water to remove excess ink from their brush. It is interesting to note that most known examples of brush washers are made from porcelain or, less frequently, from stone. This glass washer would have been worked as if it were stone by socketing it on a lapidary wheel and carving it.

|

Scholar’s Stone, 11th Century

China

Stone, wood and lacquer; 16 × 13 × 4 3/4 in.

2014.14.1

Gift of Anne and Long Shung Shih |

Other Desk Toppers

Scholar’s stones—also not to be confused with ink stones—were admired by the Chinese scholar class for the way in which they represented the metaphysical characteristics important to this class of men as early as the Song Dynasty. Large stone formations were displayed outside in gardens while smaller versions of these stones would be mounted on stands and displayed inside scholars’ studies.

Text and images may be under copyright. Please contact Collection Department for permission to use. References are available on request. Information subject to change upon further research.

Comments