|

Rogers is So Sleepy, April 20, 1864

William Henri Bonney (American, 1841-1867); Camp Nelson, Kentucky

Pencil on paper; 5 × 8 in.

17450

Gift of Mr. R. H. Hill |

Uncivil at Best

Causes are just or unjust, but war is indisputably an awful thing for individuals. Fought over slavery and states’ rights, America’s Civil War was the bloodiest in the nation’s history, dwarfing the number of casualties seen even in World War II. In the South, almost every other man who served was either killed, wounded, captured, or went missing. The stress that the loss of even one loved one breeds is immense, and that multiplied by the 620,000 casualties impresses the awful impact of the war. This post looks at a selection of drawings by William Henri Bonney, a Union soldier in the Civil War who fancied himself an artist but about whom almost nothing is known. Between 1862 and 1867 he created 27 pencil and ink on paper works, each of which speak to but most of which carefully avoid the grotesque wartime context in which they were made.

|

Pages From a Sketchbook, 1860s

William Henri Bonney (American, 1841-1867); United States

Pencil on paper; 9 1/8 × 11 1/2 in.

17463

Gift of Mr. R. H. Hill |

Oh, Hi Ohio

No formal biography of William Henri Bonney has ever been written, though there are notes about the artist from the donor. It is unclear what exactly the relationship of the donor was to the artist and given that the drawings were donated 66 years ago it is probable that we will never know for certain. Based on entries from the 1850 US Census and US Civil War Soldier Records and substantiated by locations written on his drawings, William H. Bonney was born in 1841 somewhere in Ohio to Franklin Bonney and Mary Ann (van Slyke) Bonney. He had six siblings. His first recorded enlistment took place on July 27, 1863 at the rank of Corporal. He was organized into Company M, Ohio 2nd Heavy Artillery Regiment on September 9, 1863. Company M spent significant amounts of time at Munfordville, Kentucky, and Camp Nelson, both locales where Bonney drew consistently. The entirety of the Ohio 2nd Heavy Artillery Regiment had 2,400 men in it and of them only three were killed during combat, this is tempered somewhat by the 173 men that died of disease.

|

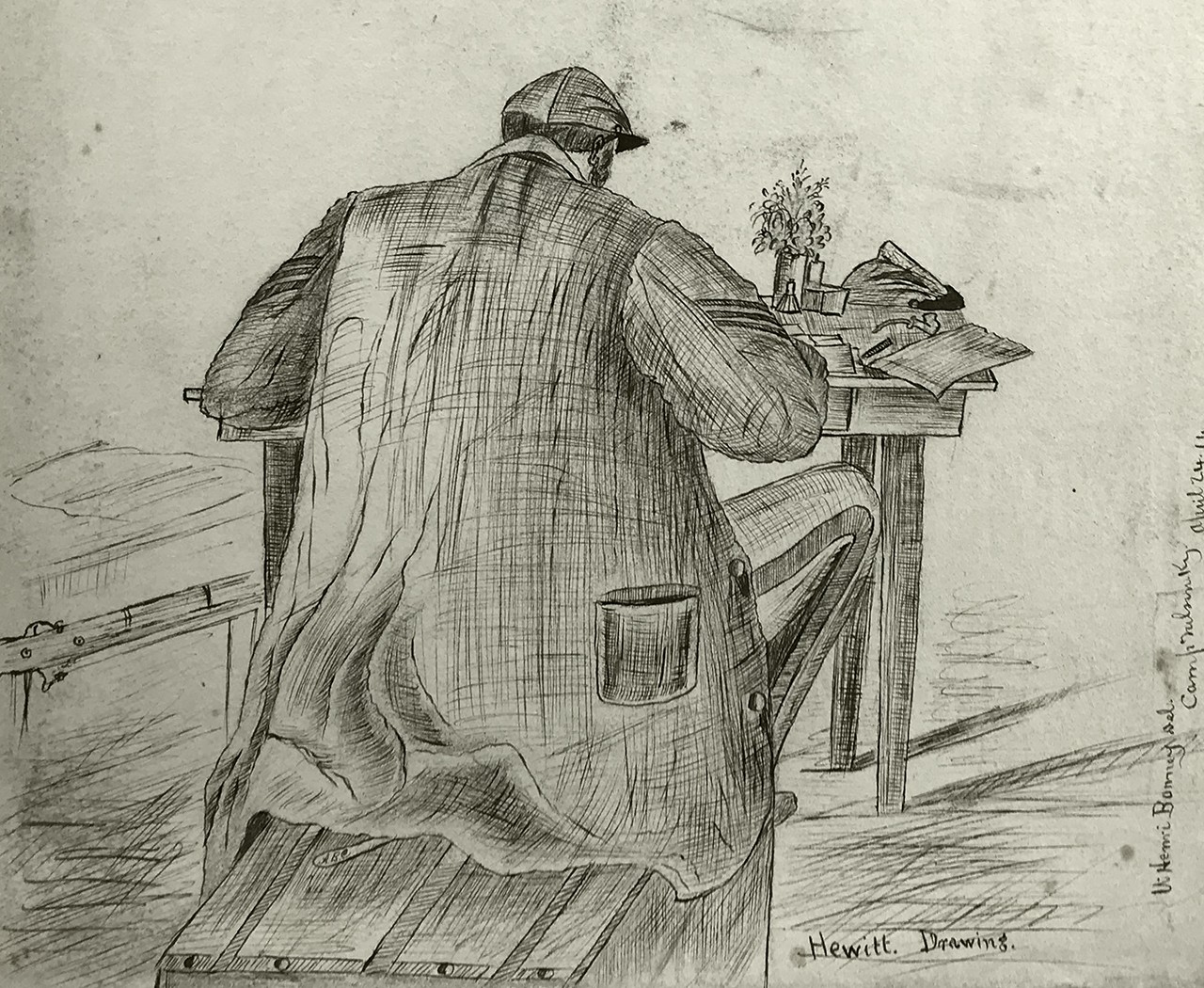

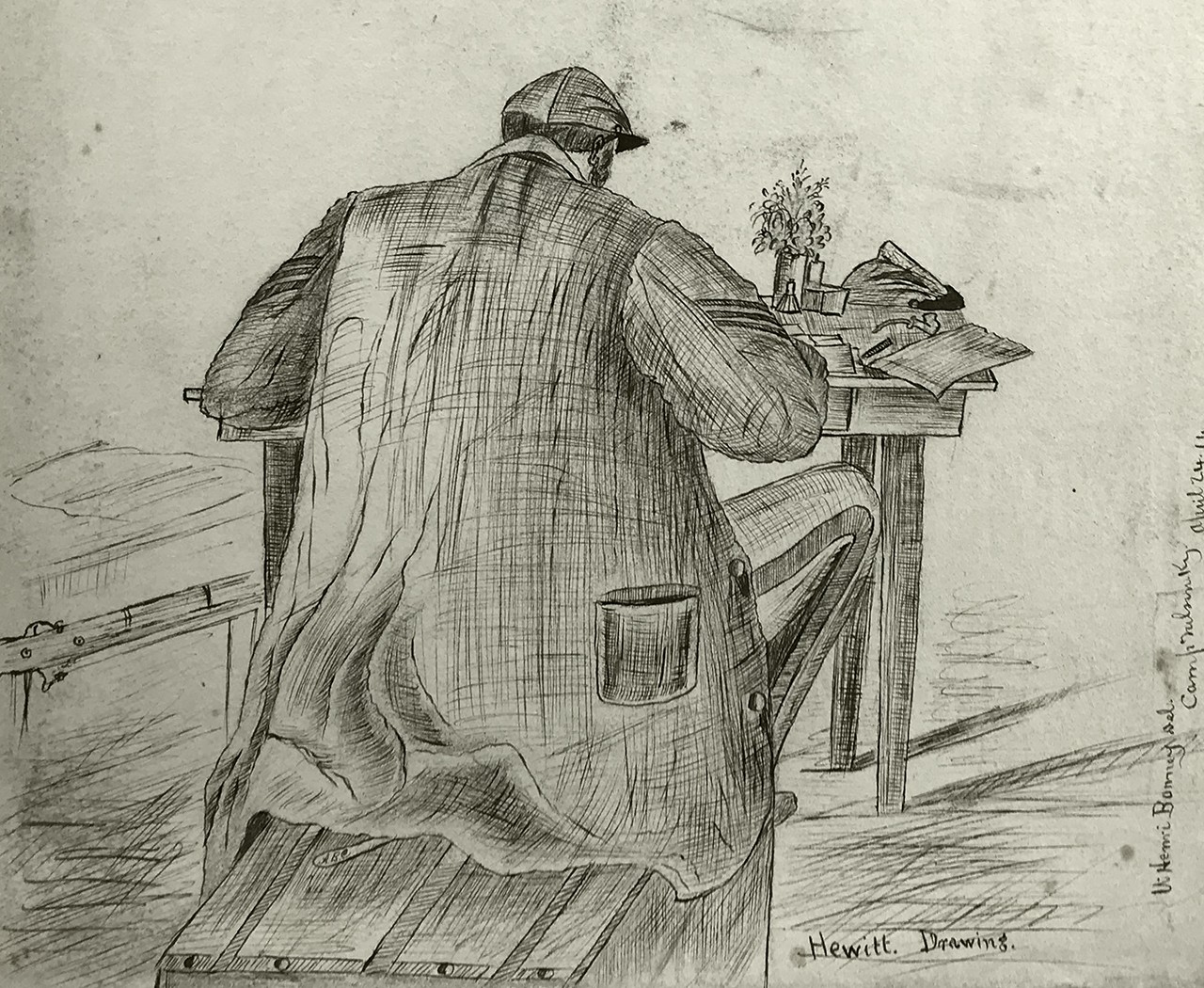

Hewitt Drawing, April 24, 1864

William Henri Bonney (American, 1841-1867); Camp Nelson, Kentucky

Pen and ink on paper; 7 1/8 × 7 3/4 in.

17461

Gift of Mr. R. H. Hill |

Ceasefire

If it seems like Bonney’s drawings are oddly devoid of fighting, it may be that he experienced little of it or it might speak to something else entirely. There are only a few instances in which Company M did any fighting, and those mostly took place in August of 1864 when they were charged with defending against and then chasing Confederate General Joseph Wheeler. Even given the lack of action, it seems odd that none of the 29 works by Bonney so much as include a firearm. The only one which even references shooting is a grouse hunt. What many scenes do represent is the daily life of Company M. For example, there are three illustrations at Camp Nelson: belying the artist’s shortcoming in perspectival study rather than a modern approach to art, this drawing of the wide-hipped Sgt. J.E. Hewitt shows that Bonney was not the only one to spend his downtime at camp sketching; another portrait depicts a “sleepy” fellow soldier; and a third, not featured in this post, shows a nearby rock outcropping. Certainly, Bonney would have been reprimanded for bringing his sketchbook into battle, but it might not unreasonably be extrapolated that drawing was far more an escape than a chronicling of his time in the army.

|

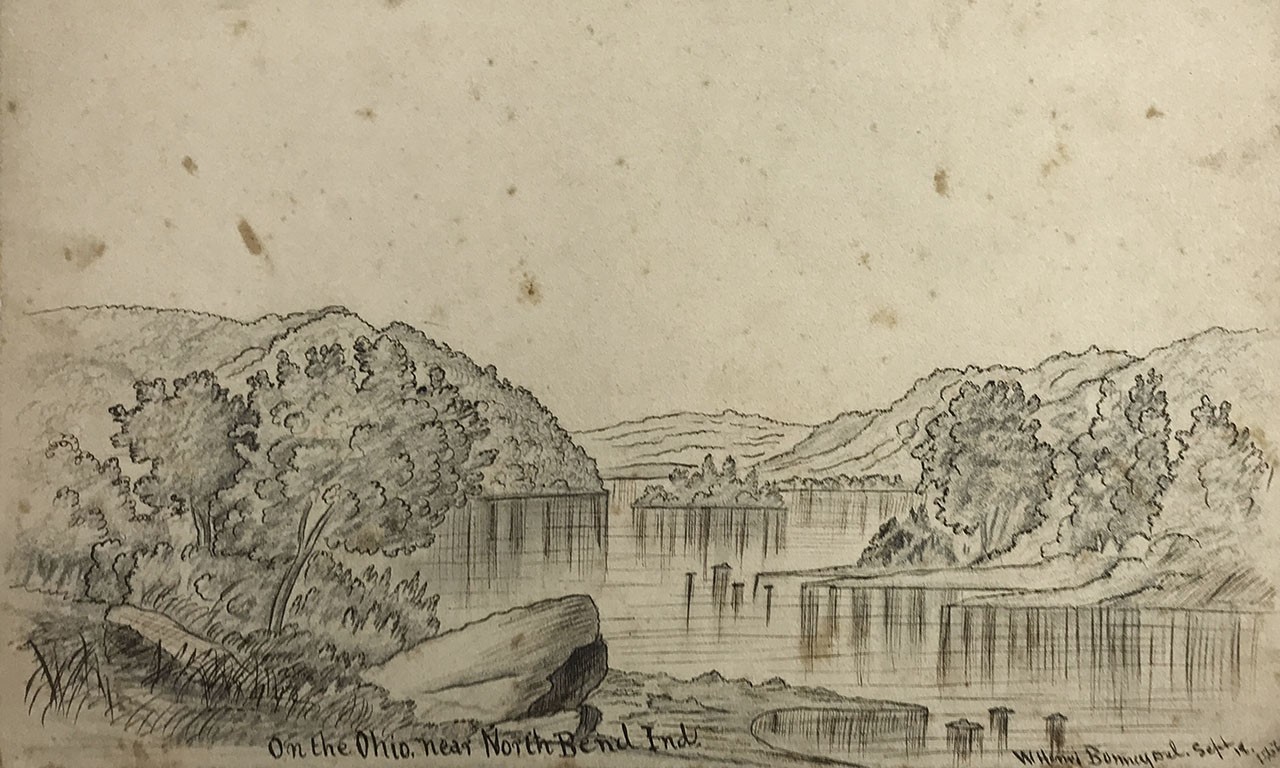

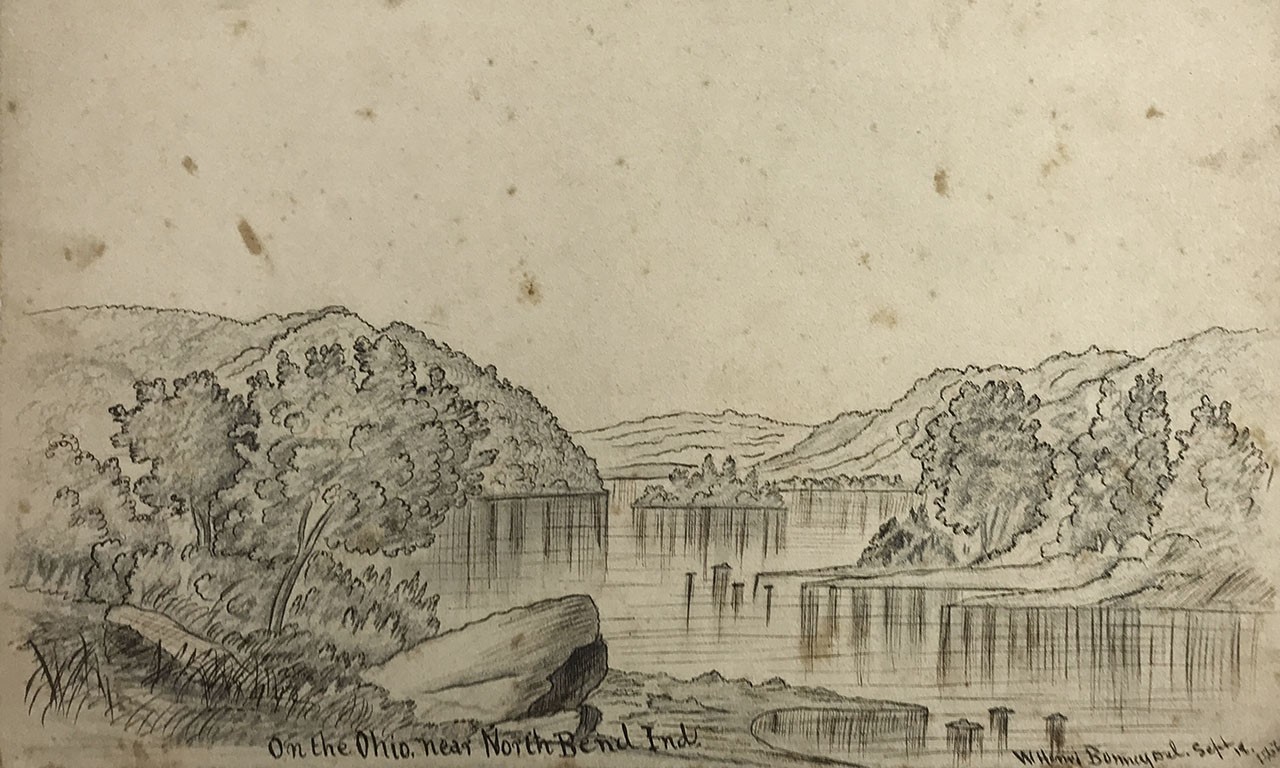

On the Ohio, September 18, 1863

William Henri Bonney (American, 1841-1867); Near Louisville, Kentucky

Pen and ink on paper; 8 3/8 x 5 1/2 in.

17442

Gift of Mr. R. H. Hill |

Won the War, Lost His Life

Perhaps the most historically valuable of the drawings are ones which tie place to specific dates. While aboard the Steamship Thistle, originally a civilian ship which was requisitioned for the war, Bonney drew this gentle scene on September 19, 1863. The ship was at the time on the Ohio River near Louisville, Kentucky. Jointly the drawings roughly track Bonney’s journey from Cincinnati, Ohio to Munfordville, Kentucky and from there to Camp Nelson, Kentucky and finally to Knoxville, Tennessee in October of 1864. After that point, there is not another dated drawing until after the war. During those years he apparently served as a commissioned officer in the US Colored Troops 1st Heavy Artillery Regiment, but the details of this time are not known at all. White officers of Black troops were often executed upon capture by Confederate forces, making this a somewhat dangerous assignment. When the war did end, Bonney continued to draw, but it would not be for long. Just two years after the end of the Civil War, Bonney died from a now-unknown cause on October 22, 1867 in Conneaut, Ohio. He was only about 26 at the time.

|

An Ideal Study, March 1866

William Henri Bonney (American, 1841-1867); Chattanooga, Tennessee

Pencil on paper; 10 3/4 × 12 7/8 in.

17466

Gift of Mr. R. H. Hill |

The Castles of Tennessee

The most fantastic works by Bonney are not those grounded in his historical surroundings. Like New England scrimshanders both preceding and succeeding him, he often recreated illustrations in books. The maps of Asia and Africa from his sketchbook appear to be just that. Other drawings such as the Wreck of the Bohemian also seem to be traced or otherwise copied from woodblock prints. But he is most at ease in his illustrations when evoking artists of the Hudson River School. Each of his river scenes is romanticized to a varying degree with riverboats and castles anachronistically existing side by side. It is apparent from his sketches that architecture was a primary interest to him, these drawings let him build in the otherwise unpopulated hillsides of Tennessee. The donor’s claim that Bonney was also a cartographer and an oil painter, unfortunately cannot be confirmed. It would be interesting to see what Bonney might have produced in a studio rather than fighting successionists to grisly ends.

A final note: in an interesting coincidence the artist’s name—spelled Henry with a “Y”—became well known when Billy the Kid assumed it as a pseudonym about ten years after Bonney’s death. There appears to be no connection between the two.

Text and images may be under copyright. Please contact Collection Department for permission to use. References are available on request. Information subject to change upon further research.

Comments