|

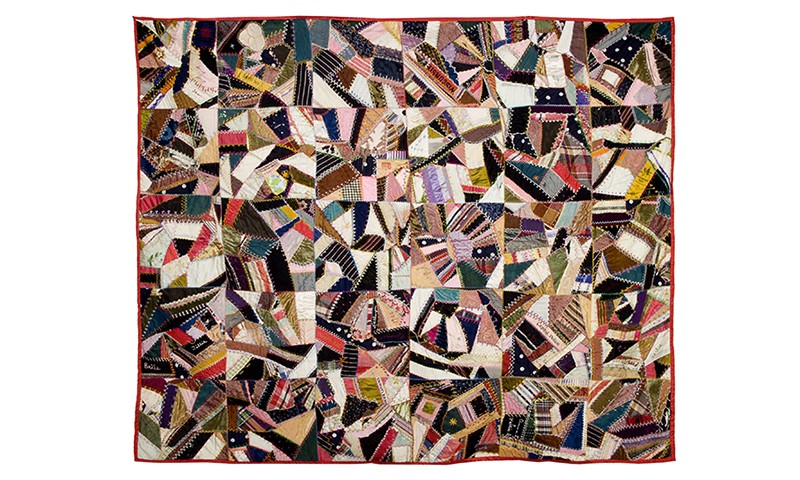

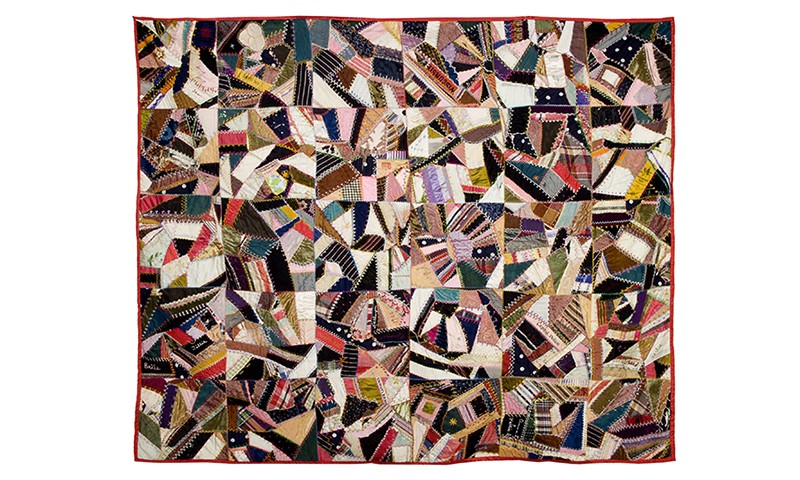

Crazy Quilt, c.1900

Sarah Ann Hinkley Tucker; Whitehall, Wisconsin

Silk and velvet; 60 x 75 in.

80.35.1

Gift of Mrs. Marjorie H. Carr |

Quilty as Charged

One of the earliest, largest, and most-often exhibited collections of Americana at the Bowers is the museum’s collection of quilts, ranging in date from our nation’s independence to the end of the 20th Century and featuring examples of almost every quilt style created therein. Their name a dead giveaway, it should come as little surprise that the most dynamic of all these styles fall under the label of crazy quilts. In this post we look at four examples of the Japanese-inspired crazy quilts in the Bowers’ collections; examining their genesis, the reasons why they were so broadly adopted, the attributes making these quilts unique, and finally, the legacy of their short prevalence in American quilting.

|

Crazy Quilt, 1888

Unknown quilter with initials LAP; possibly North Dakota or Alaska

Velvet, rayon, silk and other material; 64 1/2 x 66 3/8 x 1/2 in.

2013.4.1

Gift of Jennifer K. Hans, Trustee, Vincent and Geraldine Orbish Trust |

No Passing Craze

The Bowers Blog has previously explored the role of Japanese art at the Centennial Exposition held in Philadelphia in 1876, not the least of which was a Meiji government-sponsored plan to jumpstart Japanese foreign trade. The effort proved to be highly successful, initiating a wave of interest in Japanese art and culture which still resonates in America to this day. In the United States quilts had already taken on many different designs, but these had always been symmetrical across at least one central axis. Japanese art introduced the United States to an entire universe of asymmetry, and no single object type was more captivating to American quilters than Japanese glazed pottery. Contrary to popular belief, the term crazy in crazy quilts does not come from the wild and asymmetrical signature designs of the quilts, but instead from the more obscure definition of ‘craze:’ the intentional production of a network of cracks across a surface. It had not been Japanese quilts, but the crazed glazes of Japanese pottery that inspired a new movement of fragmented American quilting.

|

Crazy Quilt, c. 1900

Sarah Ann Hinkley Tucker; Whitehall, Wisconsin

Silk and velvet; 60 x 75 in.

80.35.1

Gift of Mrs. Marjorie H. Carr |

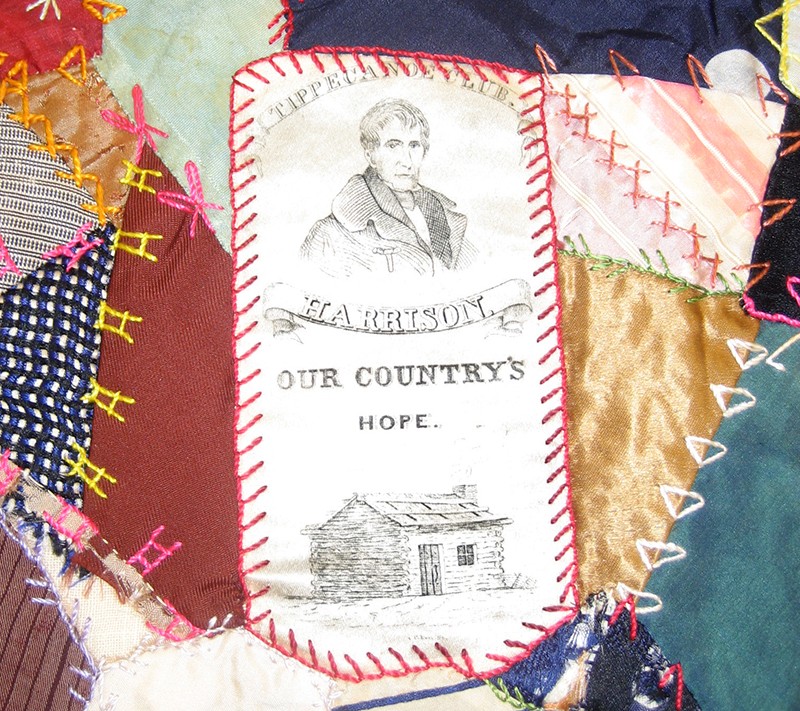

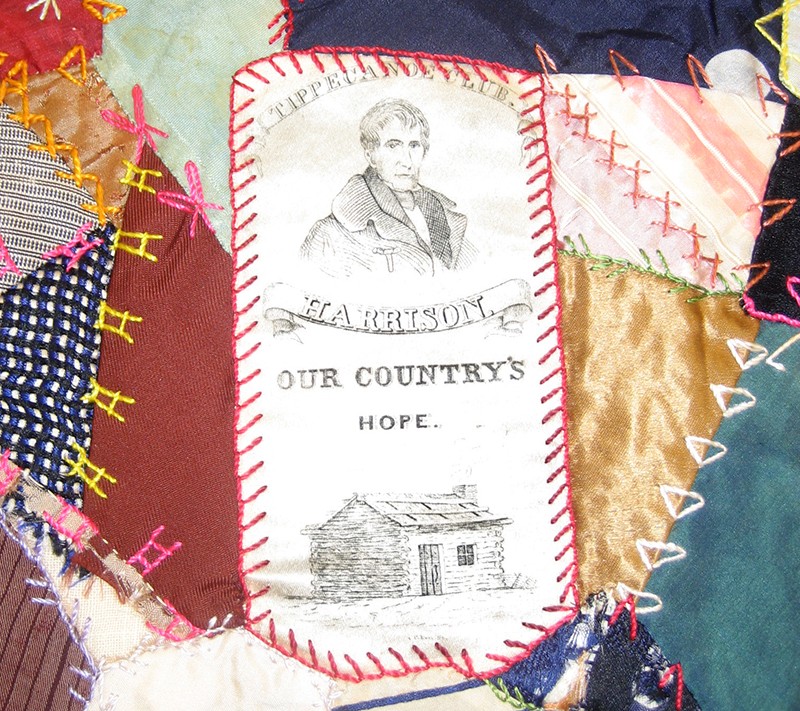

Tippecanoe and Silk Scraps Too

As crazy quilts spread across the United States through magazines, quilting circles, and word of mouth, the new style was readily adopted for a several reasons. Patchwork quilting in the United States dated back to colonial times, but it had never been so in vogue. Formerly, sections of fabric had needed to fit specific shapes, but with crazy quilts the design of the quilts could be informed by the pieces of fabric available to the quilter. This happened to coincide with the first significant price drop for silk in the United States. Increased silk sales and usage also meant that a good amount of excess silk scraps were created and sold at extremely low prices. The patchwork designs were hardly limited to silk, though. Fragments from clothing were a common find, but even additions such as the campaign advertisement for the 1840 presidential candidate William Henry Harrison we see in one of the Bowers crazy quilts would have been an anachronistic but not an entirely unexpected inclusion in a turn of the 20th Century crazy quilt. Crazy quilts also presented a unique opportunity for quilters to show off. While the resulting quilts can appear haphazard to the uninitiated, their construction is in fact a wildly complex puzzle. Scraps had to be measured and fitted to one another, almost as if piecing together an array from shattered mirrors.

|

Crazy Quilt, c. 1881

Maker unknown; American

Silk and velvet; 78 x 73 1/4 in.

37477

Gift of Mrs. Louise Grouard Mock |

Border Embroidery Never Bored Her

Even considering their unique components and the difficulty of creating a cohesive design from scraps, perhaps the most impressive aspect of crazy quilts were embroidery patterns used to stitch together the various patches that went into a crazy quilt. Even just in the eleven examples of crazy quilts at the Bowers, one is able to distinguish countless embroidery patterns including ones inspired by flowers, butterflies, crosses, and all manner of geometric designs. Embroidery was used for more than stitching as well. Otherwise monotonous swaths of fabric might be embroidered with the quilter’s initials or any subject that came to mind. Crazy quilts’ original inspiration from Japanese culture is well-felt here too: Japanese fans, tea kettles, and women holding paper parasols can all be found embroidered into the silk and velvet patches of an 1888 quilt in the Bowers’ collections.

|

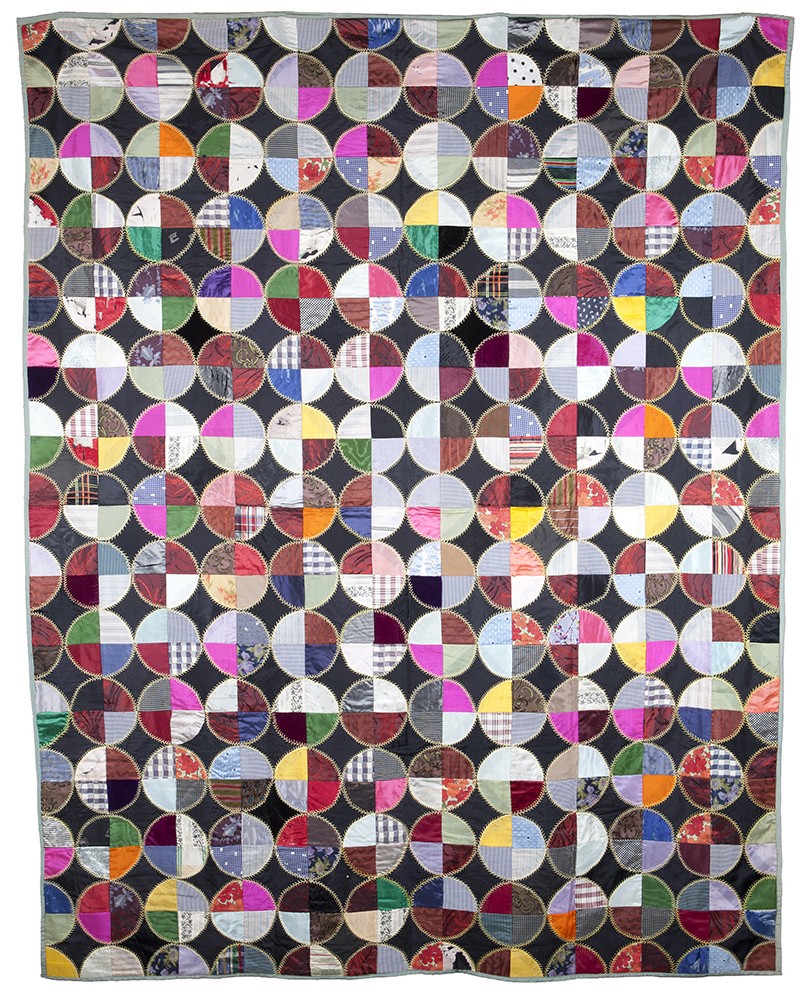

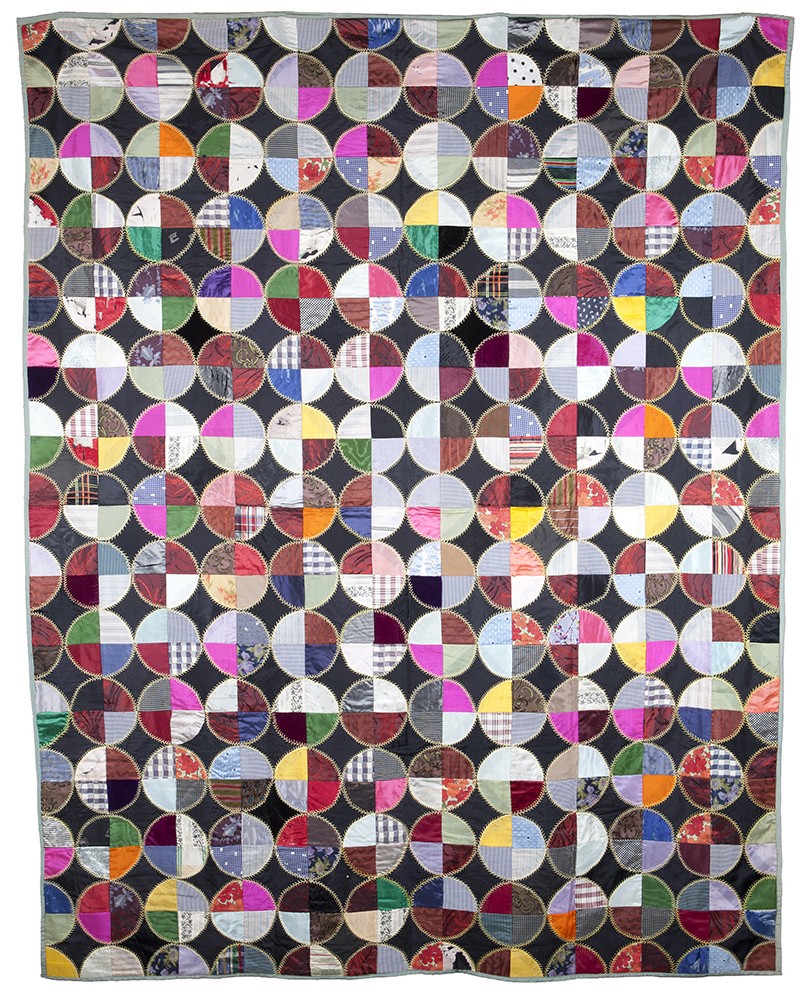

Baseball Pattern Quilt, c. 1914

Maker unknown; American

Silk, cloth and yarn; 61 1/2 x 78 in.

30857

Gift of Mrs. Mildred E. Campbell |

The Windup and the Stitch

Shortly after praising crazy quilts as the only imaginable future for quilting, the very same magazines reversed their message to say that crazy quilts had been a “childish” venture. In the broadest sense, crazy quilts moved out of the mainstream after less than a decade of prevalence. However, the positive attributes which had first drawn quilters to making crazy quilts meant that they never disappeared altogether. Quilters steadily continued to create crazy quilts from scrap pieces of silk until the early 20th Century. All the while crazy quilts were evolving and synthesizing with traditional American quilt styles. The above rare hybrid quilt has been described as a “baseball” pattern quilt due to the 180 complete and partial circles formed from 616 quadrants of miscellaneous patches. The stitching, also an essential feature of the crazy quilt, is uniformly done using a feather stitch; the result being that the stitch looks aesthetically similar to the stitching used on baseballs. As quilting continued to develop throughout the 20th Century crazy quilts continued to serve as a driving inspiration for quilt design.

Text and images may be under copyright. Please contact Collection Department for permission to use. References are available on request. Information subject to change upon further research.

Comments