|

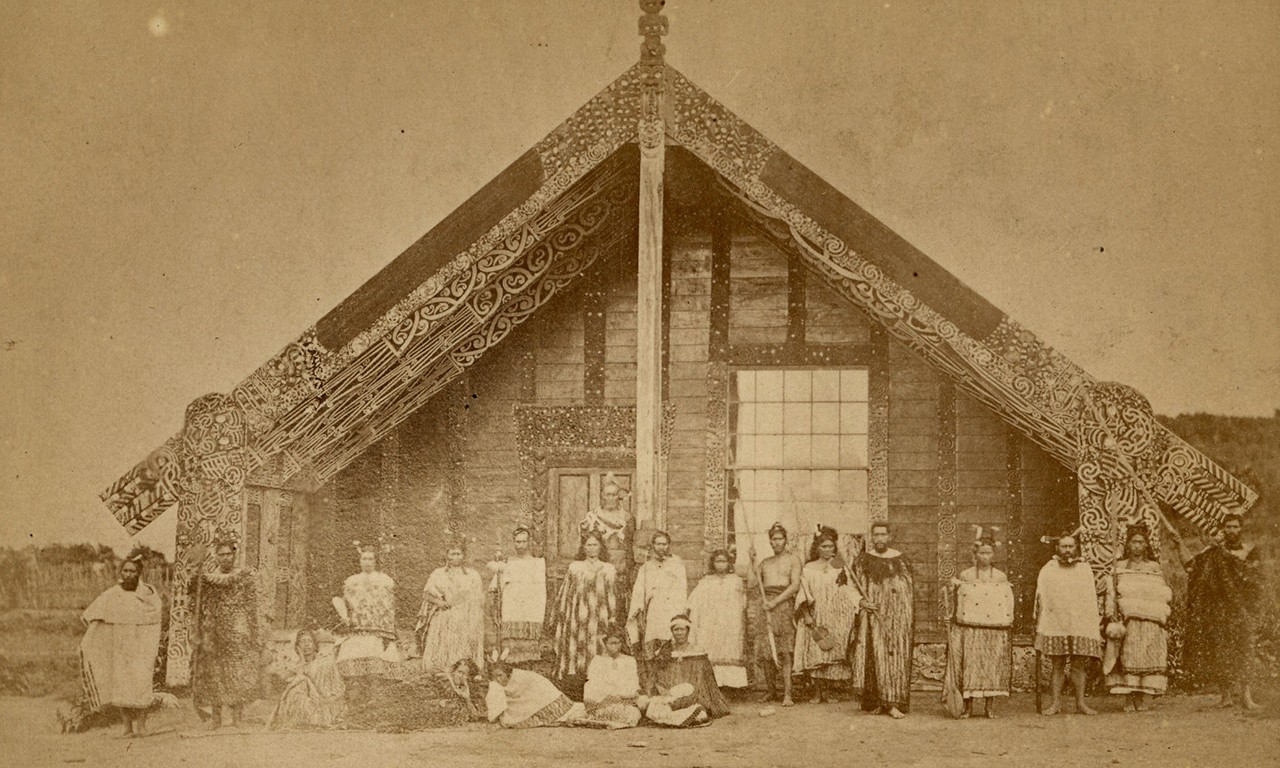

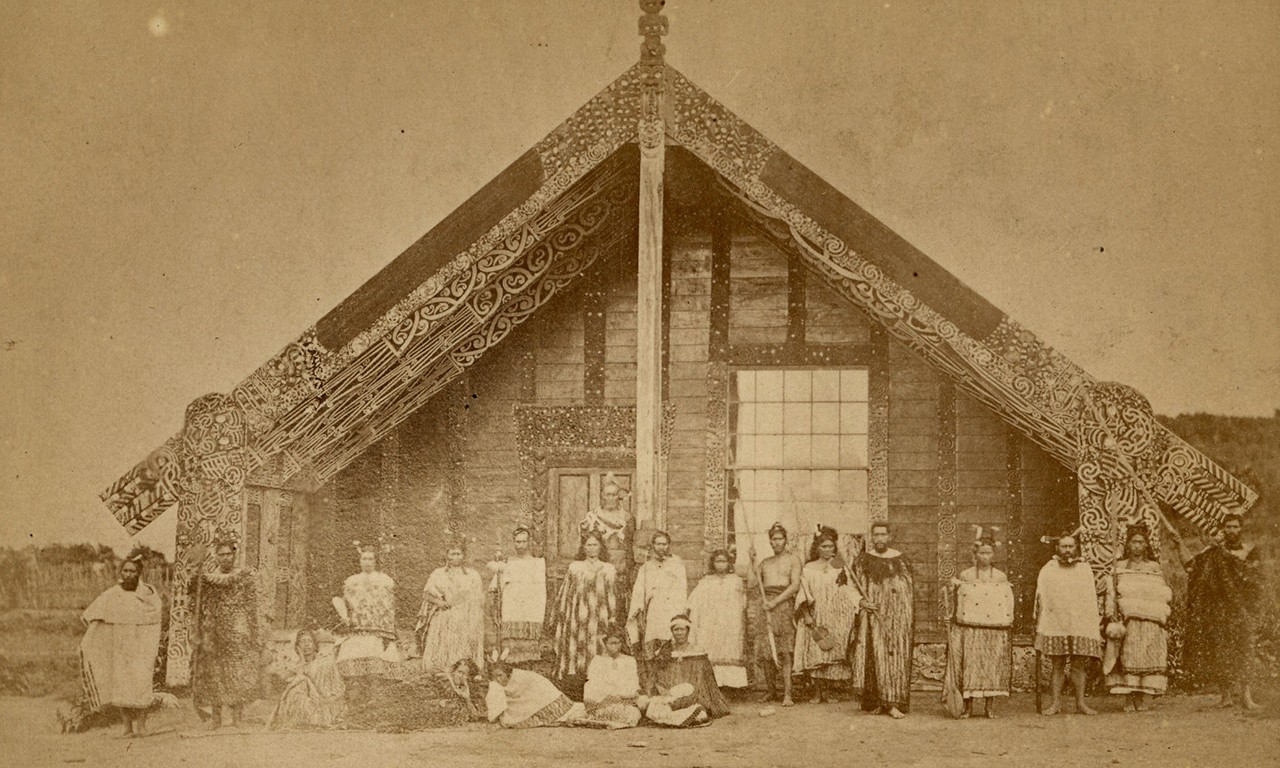

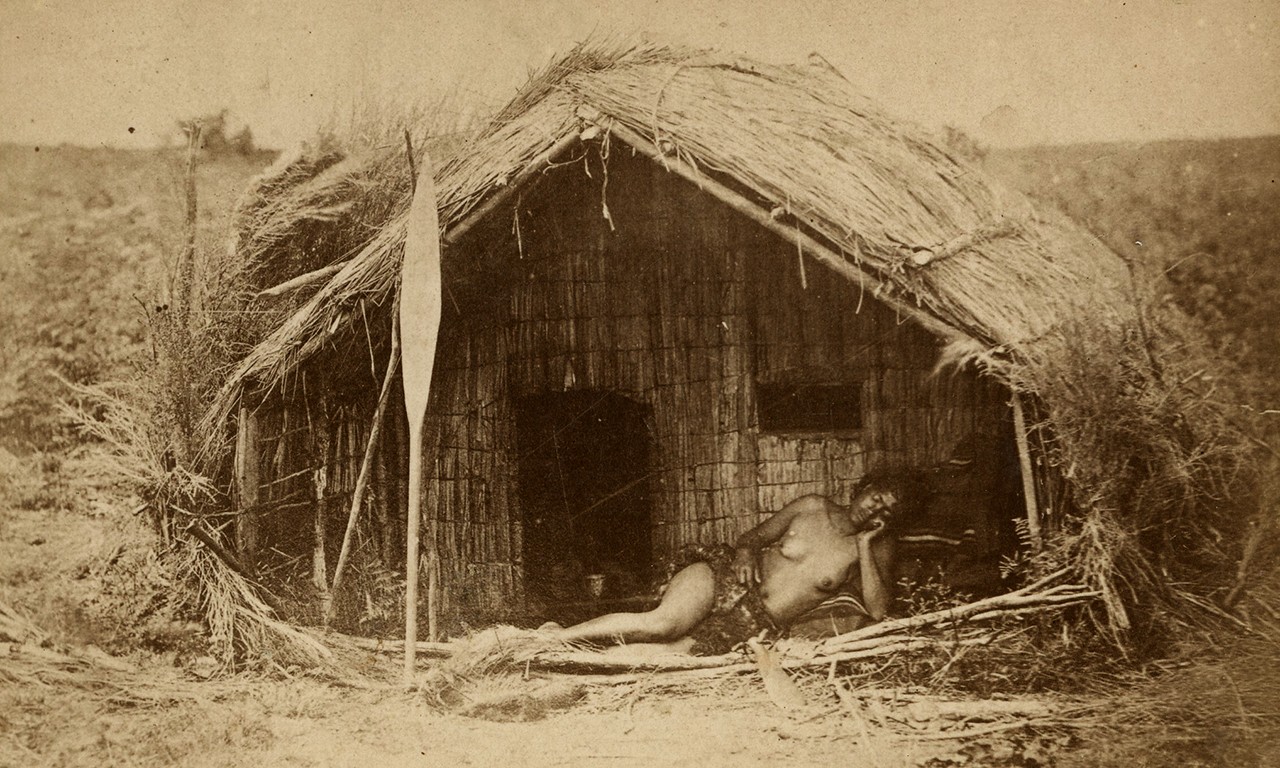

New Zealand Council House, late 19th Century

Louis Buderus; East St., Rockhampton, Queensland, Australia

Photographic print; 2 1/2 x 4 1/8 in.

93.41.30

Gift of Mr. E. Morgan Stanley |

Days Gone By

Back in the days where proper business conduct involved handshakes rather than batting away all would-be violators of personal space with two yardsticks duct taped together, people often exchanged little pieces of paper with personal information which they called “business cards.” Indeed, this was a practice which has an incredibly lengthy history and has taken a great many forms over the years. Among the most unique of these—at least in terms of the industry built up around it—was the carte-de-visite, a calling-card-size photograph mounted on cardboard. While these originally just depicted the card holder, over time the format came to be used to depict a wide variety of subjects. In this post we look at a group of cartes-de-visite which were made in Oceania.

|

| Self portrait of André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri, c. 1884 |

The Disdéri Mystery

Given its name, it is perhaps unsurprising that the carte-de-visite was first patented in France. In 1854 a Rasputin-bearded photographer by the name of André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri designed a printing format which used a multi-lensed camera with removable slides to take up to eight exposures in a short amount of time. Two important developments came from this type of image making: first, multiple images could be made and distributed within a relatively short amount of time and second, the subject could pose or be positioned differently in each photograph. With an impressive degree of rapidity, giving someone your photographic visiting card upon meeting fast became common practice among the upper class.

|

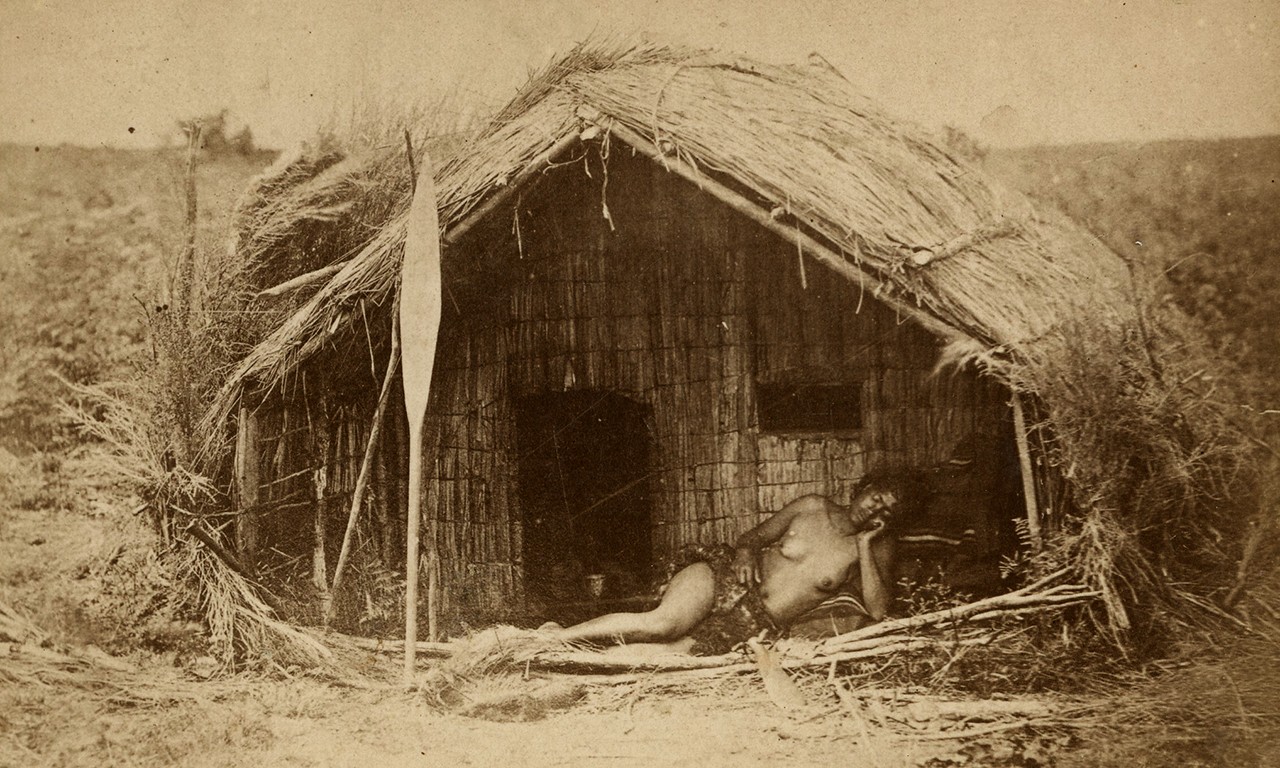

Woman Reclining Outside Home, late 19th Century

Louis Buderus; East St., Rockhampton, Queensland, Australia

Photographic print; 2 1/2 x 4 1/8 in.

93.41.36

Gift of Mr. E. Morgan Stanley |

All La Rage

The popularity of this custom helped spur the development of the career photographer and the portrait studio. Subjects posed with objects that identified their social status or line of work. Other times, people would commission photographs to help demonstrate their superior character and breeding through physiognomy, the debunked Victorian-era pseudoscience of facial divination. Whether due to one’s work, social climbing, or disdain that other pop sciences involved carrying calipers, by 1859, millions of portraits were being produced. The small size and high volume of cartes-de-visite meant that they could be purchased not only of the aristocracy but, by artists, celebrities, and the working class as well. Over time the subject matter extended to include monuments, artworks, and noteworthy people, meaning that the cards became highly collectable, a precursor of sorts to baseball cards.

|

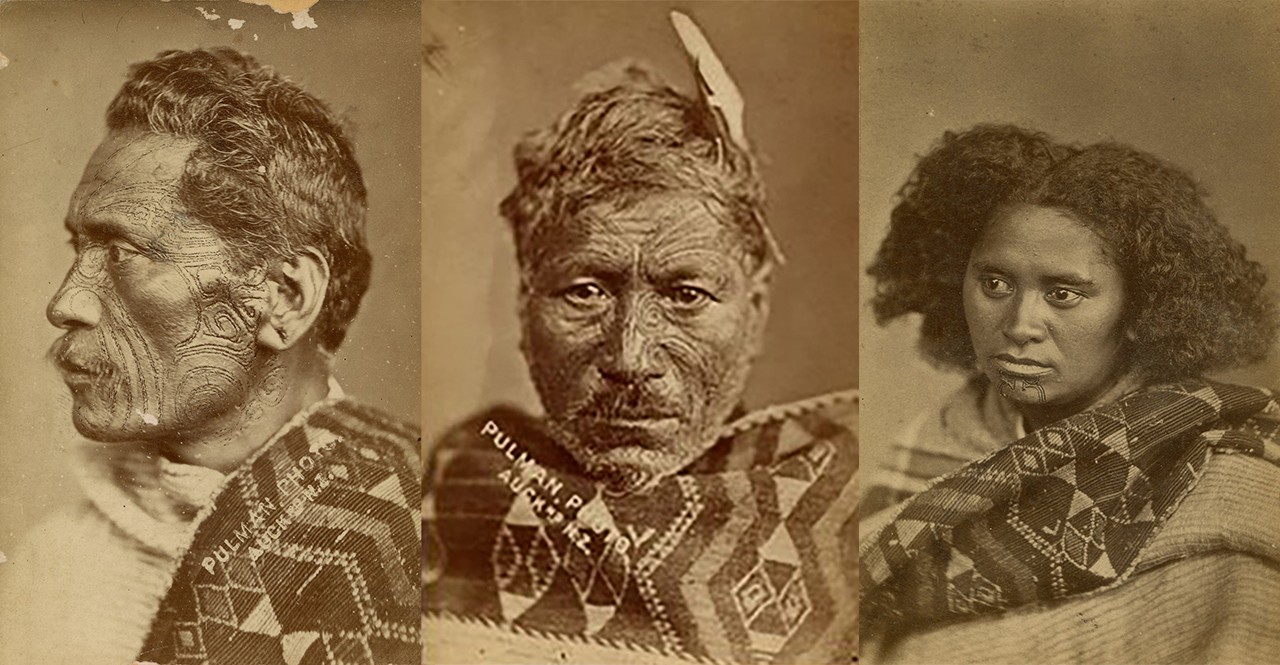

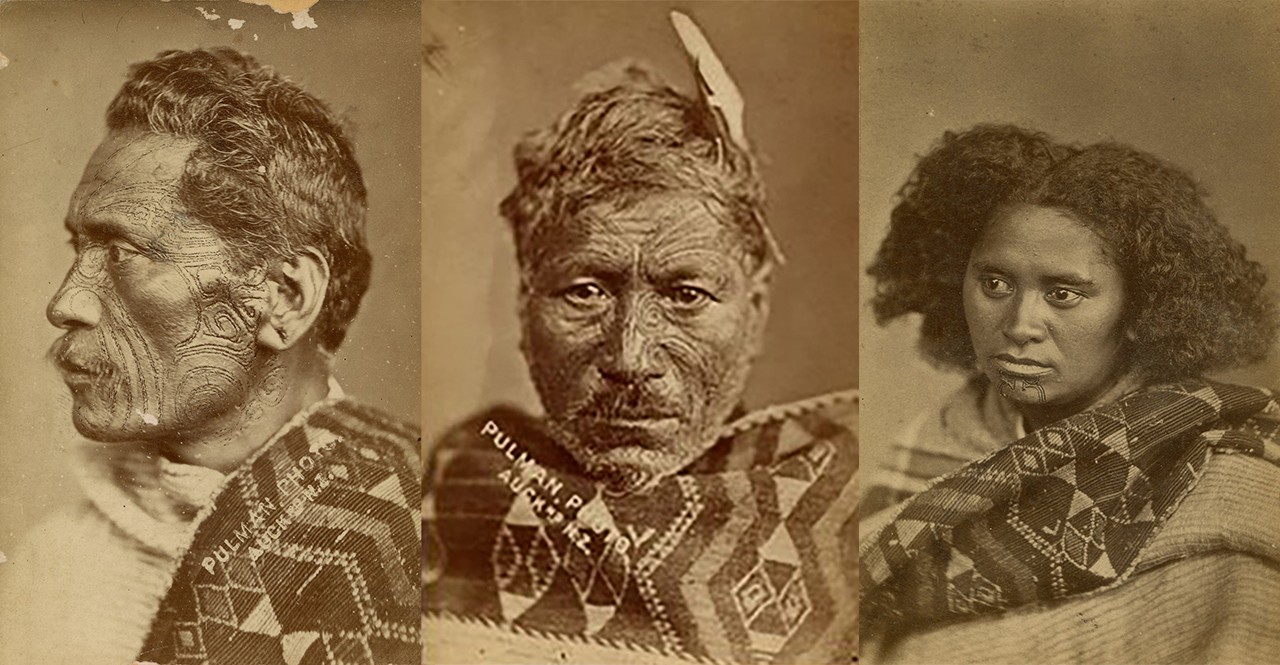

Photographs of Three Māori People, 1881

Elizabeth Pulman (British-born New Zealander); Auckland, New Zealand, Polynesia

Photographic print; 2 1/2 x 4 1/8 in. (each)

93.41.31-.32,.37

Gift of Mr. E. Morgan Stanley |

Worth 1000 Words

Between 1860 and the turn of the century the interest in images of indigenous people fueled photographers’ travel to Latin America, Australia, and many of the islands in the Southern Pacific. As seen from the several examples here, photographs were made in several styles. Many problematic examples of “ethnographic” photography have been written about, such as the adherence to methods of posing subjects with props that confused the customs, status or use of objects among people. We can see in the three photographs of Māori men and women by E. Pulman, that all three are dressed in the same textile. In a similar vein to what was mentioned before, many of the cartes-de-visite depicting people outside of Europe supposedly emphasized the negative physiognomic traits of non-Western individuals. All the same, many of these photographs represent the most objective depictions of indigenous cultures from around the world and—in rarer cases still—offer insights into now-lost cultural customs.

|

Photographs of Fijian People, 1871-79

Francis Herbert Dufty (British-born Australian, 1846-1910); Levuka, Ovalu Island, Lomaiviti Group, Lomaiviti Province, Fiji, Melanesia

Photographic print; 2 1/2 x 4 1/8 in. (each)

93.41.27-.29

Gift of Mr. E. Morgan Stanley |

Those Behind the Lens

The photographs featured in this post come from at least three different studios. We have already mentioned E. Pulman’s photographs of Māori people but have not disclosed that she was quite possibly New Zealand’s first female photographer. At the time it was incredibly rare for women to work in that line of work. Interestingly, all three of her images in the Bowers collections have post-development inkwork applied to help highlight the facial tattoos of the sitters. Francis Herbert Dufty was an English man who moved to Fiji in 1871 and set up one of the few photography studios on the islands. Though posed in a studio, the Fijians photographed by him are shown with items and garb which would have been worn at the time. The cartes-de-visite of Louis Buderus, a photographer working out of Rockhampton, Australia set themselves apart from others because they were evidently taken outside of a studio. This was not entirely unheard of, but it certainly made it difficult to ensure that the images would be of good quality. Other photographs by Buderus in the Bowers’ collections show blurred figures as a result.

Text and images may be under copyright. Please contact Collection Department for permission to use. References are available on request. Information subject to change upon further research.

Comments 1

Fascinating history...the precursor to my business cards. Enjoy immensely the historic photos.