|

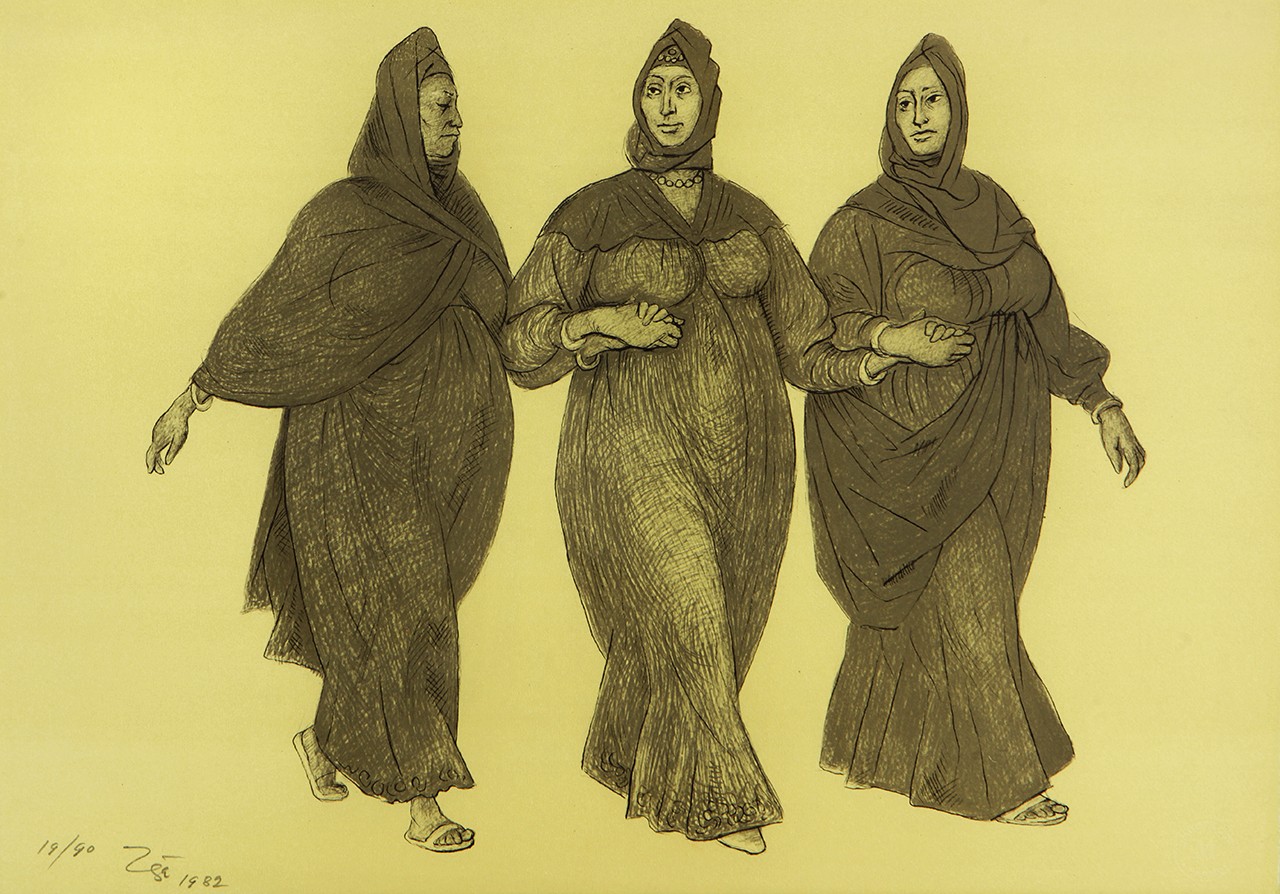

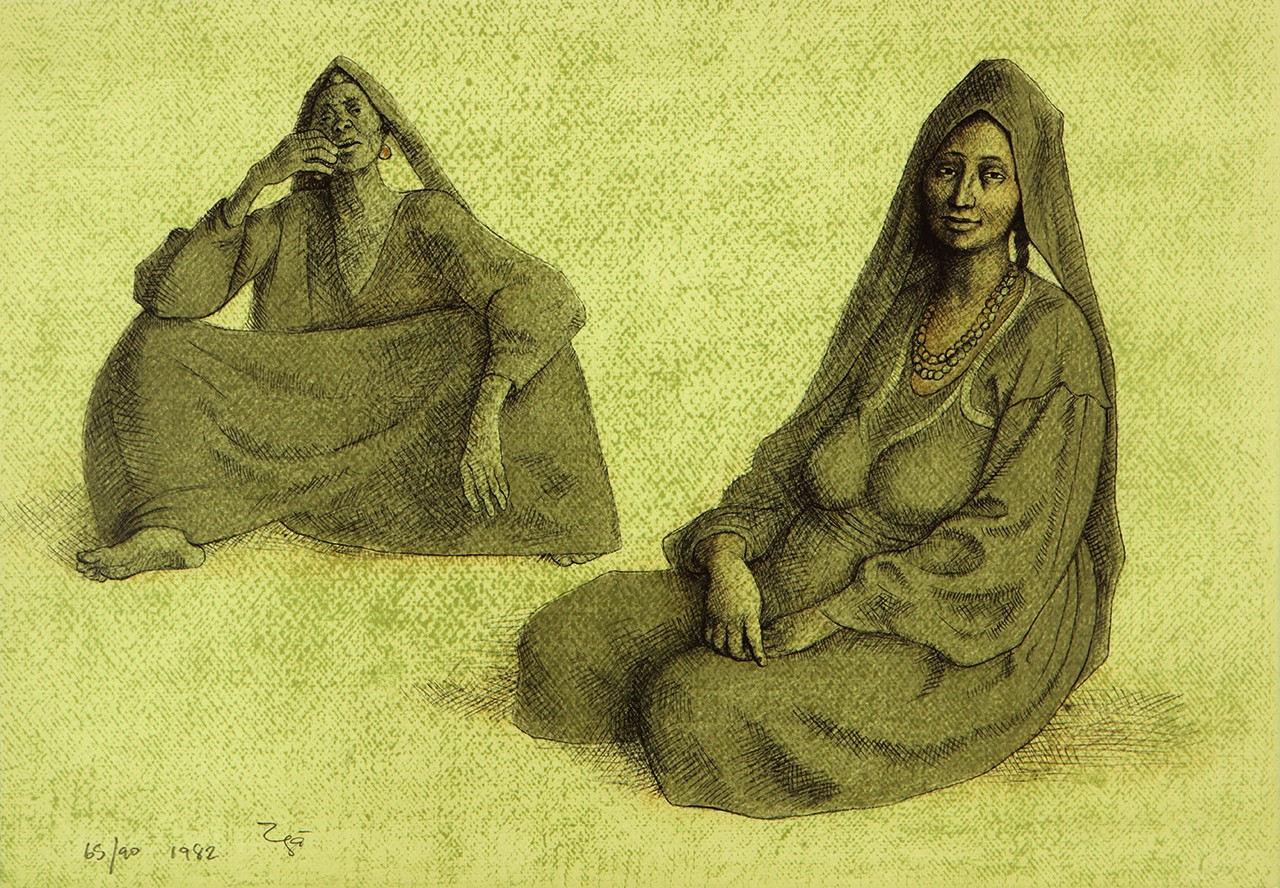

Impresiones de Egipto, Plancha 6, 1982

Francisco Zúñiga (Costa Rican-born Mexican, 1912-1998)

Lithograph on Arches; 13 ¾ x 19 ¾ in.

2016.5.13

Anonymous Gift |

A Man of Many Renaissances

Part of the incredible nature of art is the scope of what it depicts. From nonrepresentational paintings capturing feelings to photorealistic portraits, artists define themselves in many ways. When synopsizing a painter like Picasso, art historians would probably first mention style, school, or movement, but the subjects that artists are drawn to are equally important, especially when it is one that an artist returns to again and again. Today’s post looks at a group of prints and drawings by an artist who spent almost the entirety of his career focusing on and mastering the depiction of mestiza women. We begin with a biography of his life before exploring how atypical this selection of works is in Zúñiga’s oeuvre.

|

Dos mujeres sentadas, 1972

Francisco Zúñiga (Costa Rican-born Mexican, 1912-1998)

Crayon on paper; 18 7/8 x 25 3/8 in.

2016.5.18

Anonymous Gift |

About 2,020 Zúñigas

Francisco Zúñiga’s father was himself a very important sculptor in the Costa Rican capital city of San José. Throughout his life he created some 2,000 religious sculptures and—arguably more impressive—19 living, breathing likenesses, nine of whom became sculptors and one who came to be known as perhaps the most famous Latin American sculptor of the 20th century: Francisco Zúñiga. Like many of his siblings, Francisco took classes in drawing and began training in his father’s workshop around the age of 16. At this time Mexico City was a Mecca for artists looking to make names for themselves. Excited by the potential of what he could learn and bring to the city’s discourse, he moved there in 1936.

|

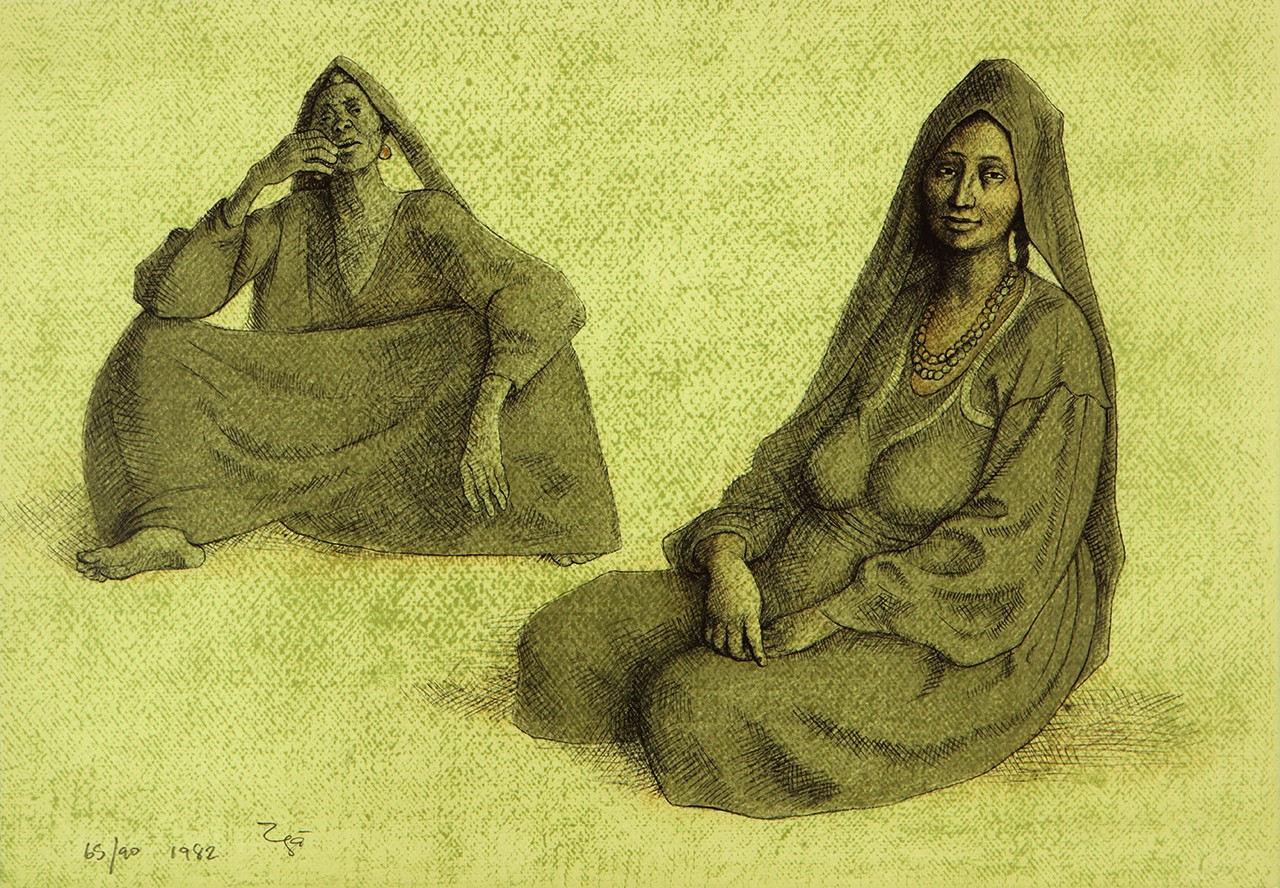

Impresiones de Egipto, Plancha 3, 1982

Francisco Zúñiga (Costa Rican-born Mexican, 1912-1998)

Lithograph on Arches; 13 ¾ x 19 ¾ in.

2016.5.11

Anonymous Gift |

Locus Focus

The air in the city was energized with political movements and artistic philosophies battling for public opinion on canvases and muraled walls. Zúñiga’s influences in the new city were many: he began studying at the Escuela de Talla Directa with Guillermo Ruiz and Oliverio Martinez; he briefly worked with Henry Moore and others who spent their whole lives decoding the puzzle of the human form in sculpture; and shortly after his arrival he visited the Museo Nacional de Antropología and became interested in both the pre-Columbian figures there and in the parallels he drew between their forms and those of indigenous Mexican women. The result was, like many Mexican artists of the time, that his artwork became a synthesis of Western and pre-Columbian elements. However, perhaps due to his status as an outsider in Mexico or his early training in working with classical sculpture in his father’s studio, Zúñiga set himself apart by doing the opposite of what artists like Rivera and Tamayo did by taking traditionally Mexican elements and using them in an international context. Zúñiga applied a classical framework to the depiction of his admittedly narrow range of subject matter: indigenous Central American and Mexican women.

|

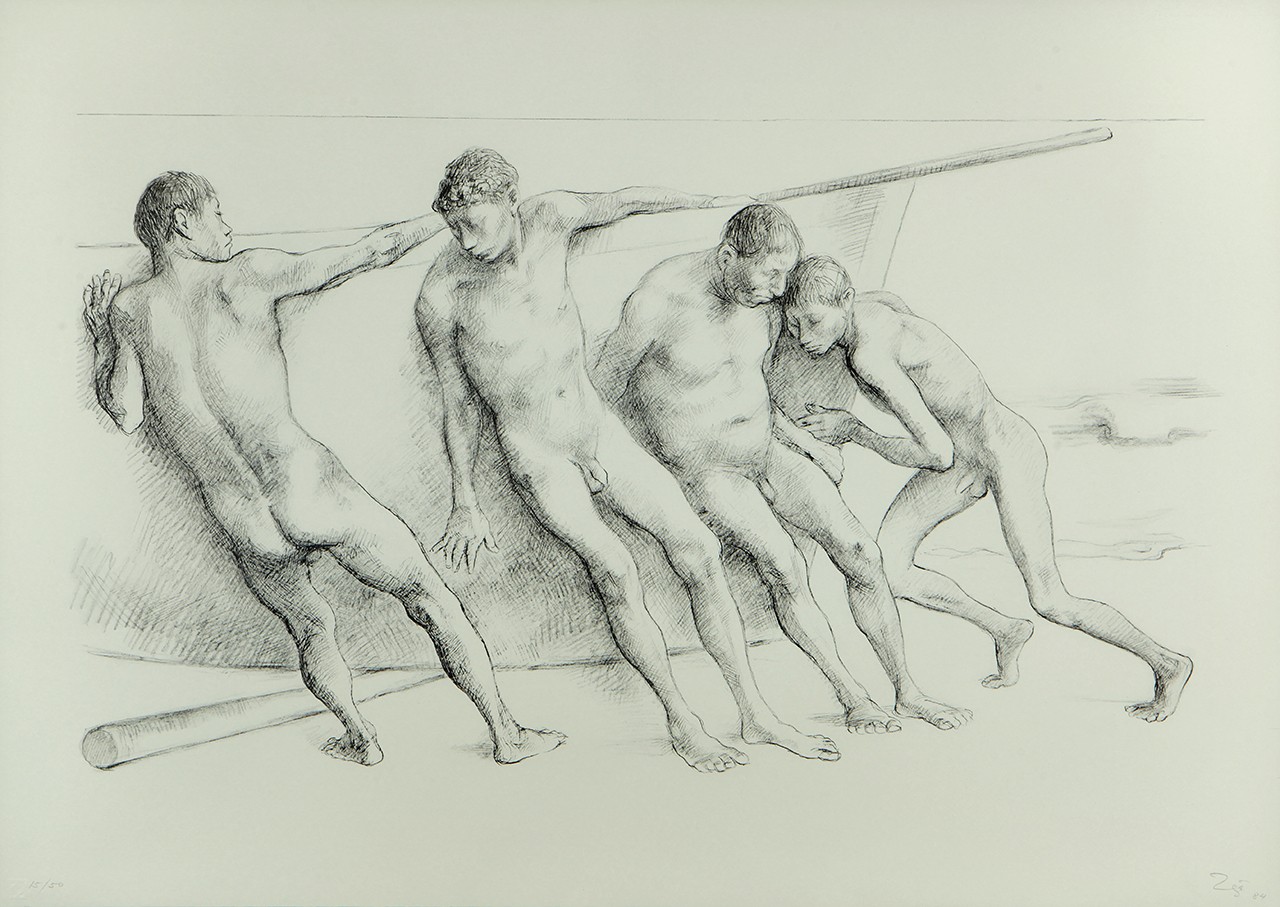

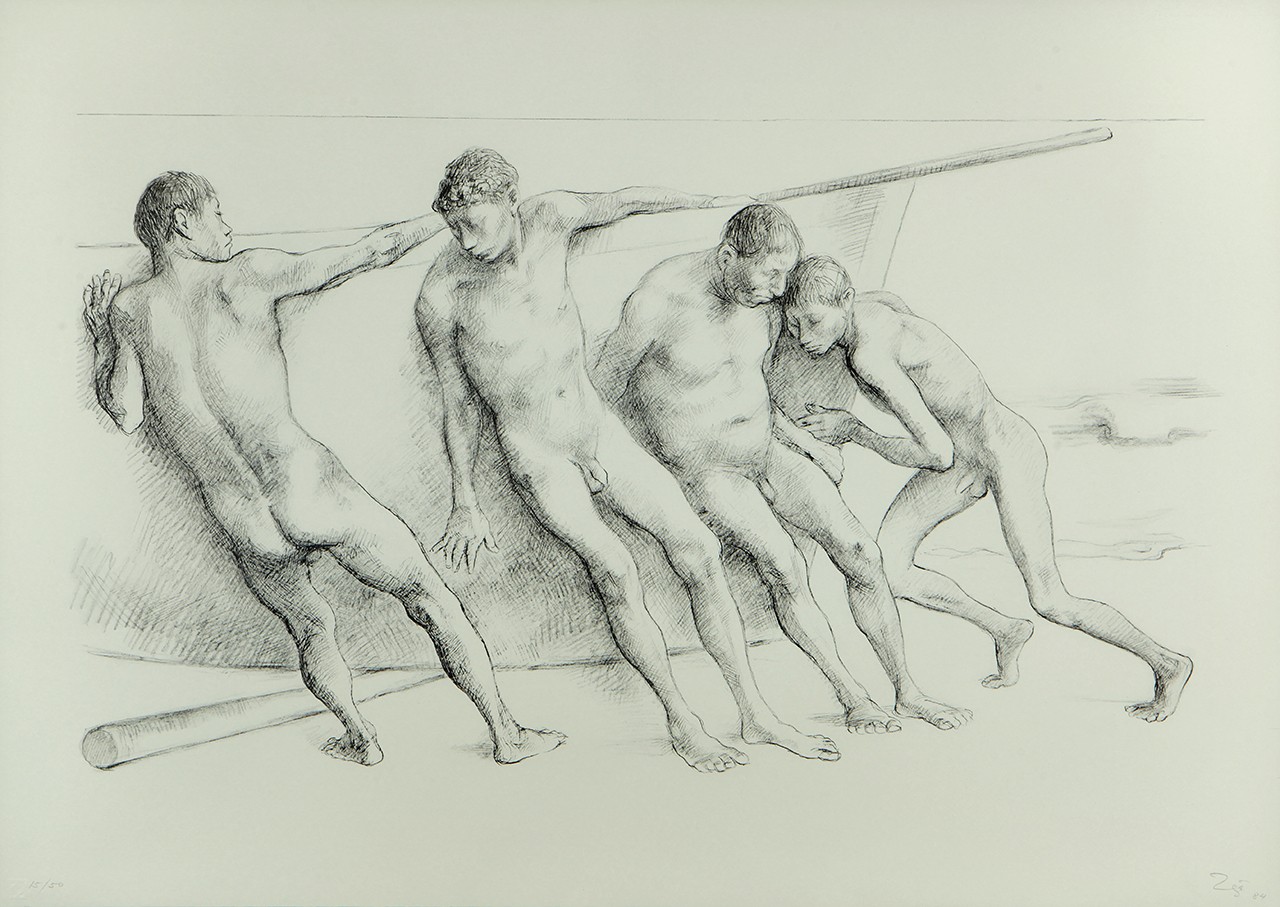

Hombres con barca I, 1984

Francisco Zúñiga (Costa Rican-born Mexican, 1912-1998)

Lithograph; 24 x 34 in.

2016.5.17

Anonymous Gift |

Late Entry to New Mediums

Only two years after arriving in Mexico City, Zúñiga began as a teacher at the Escuela Nacional de Pintura, Escultura y Grabado. His colleagues in instruction formed a prestigious group, with notable members like Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo. The Costa Rican sculptor would end up teaching there until 1970, during which time he transitioned from practicing both painting and sculpture to focusing just on sculpture and the drawings used in their planning. Mexico has had a long history with the graphic arts, but lithography began to see a renaissance in the 1960s and ‘70s. In 1972 Zúñiga collaborated on the first print in his life and rapidly became a very prolific graphic artist, reimagining the reference sketches for sculptures as proofs for democratic artworks.

|

Impresiones de Egipto, Plancha 5, 1982

Francisco Zúñiga (Costa Rican-born Mexican, 1912-1998)

Lithograph on Arches; 13 ¾ x 19¾ in.

2016.5.12

Anonymous Gift |

Wise as the Earth Itself

As already mentioned, the vast majority of Zúñiga’s artworks are of mestiza women, which makes the prints featured in this post atypical. Hombres con barca I is perhaps the only example that speaks for itself in this regard, given that it is one of the “exceptionally rare” Zúñiga works that depicts only male subjects. The remaining three prints are from his 1982 folio, Impresiones de Egipto. The artist was impressed by the monumental works of ancient Egyptian sculptors and praised their exquisite use of materials. But of the 10 prints in the folio, only one shows the architectural wonders of the Egyptians. For Zúñiga, monumentality took the sturdy, pyramidal forms of seated women who, in this instance, he presents in a strikingly similar mode to his usual stoic and fabric clad models seen in his drawing, Dos mujeres sentadas. Zúñiga’s works are grounded in emotion and in action, which might be the secret to his oft-repeated subject matter remaining nuanced even after half a century of production. The intimate, sororal relationships between his characters are defined as much by pose and nuanced body language as they are by facial expression. The volume of their bodies’—equally apparent in his two-dimensional works as in his sculpture—expressing the silent volumes Zúñiga hoped to convey.

Text and images may be under copyright. Please contact Collection Department for permission to use. Information subject to change upon further research.

Comments