|

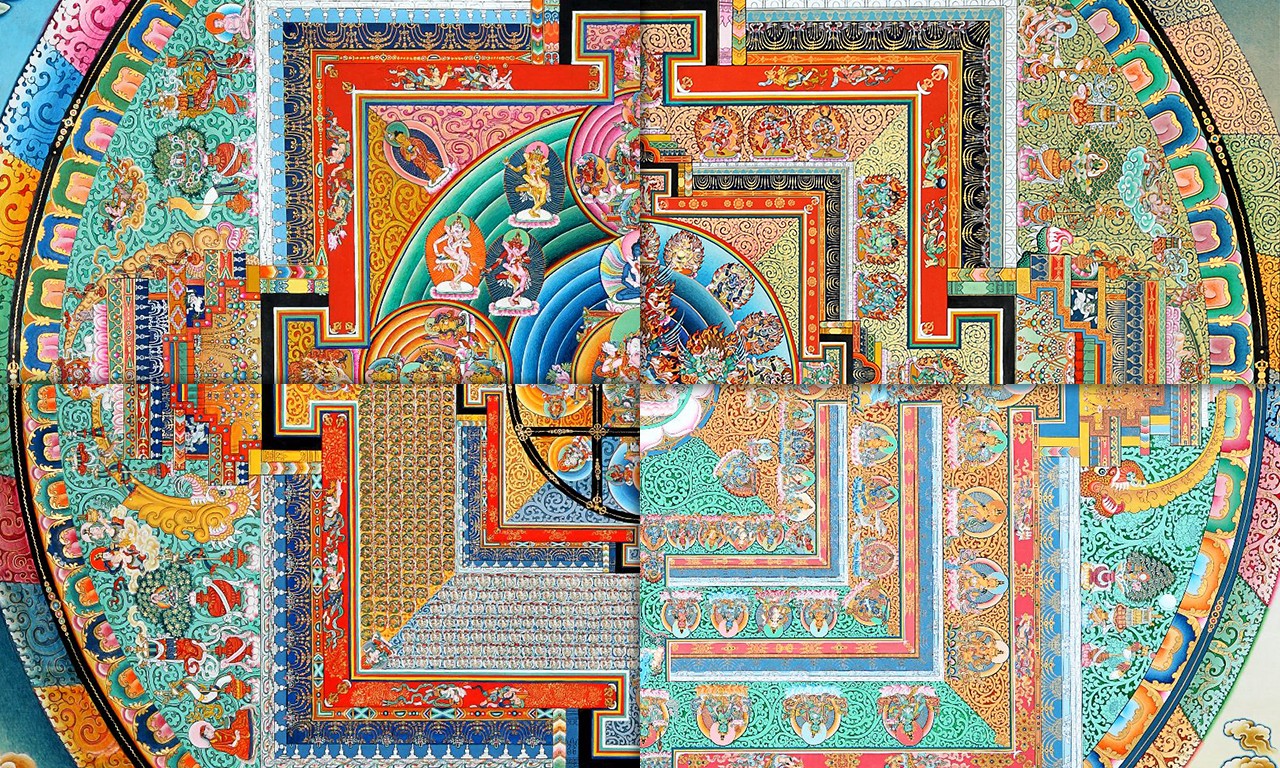

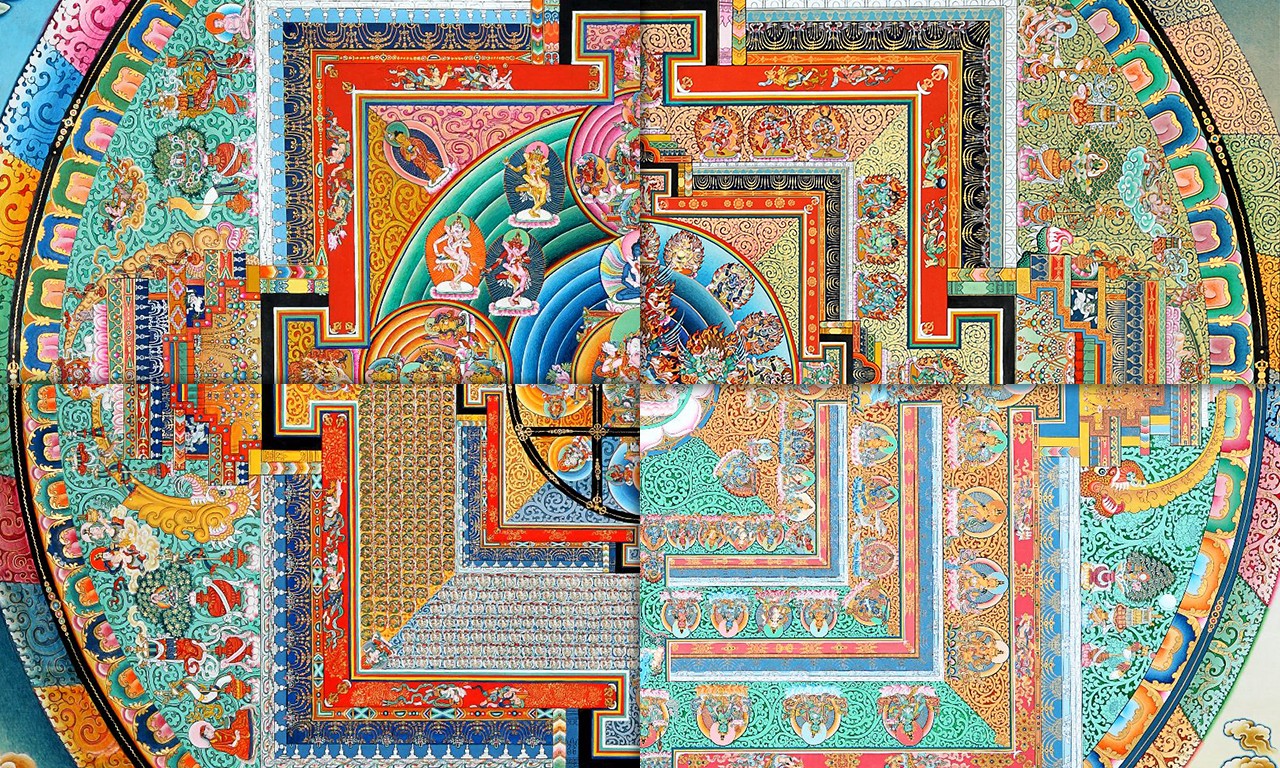

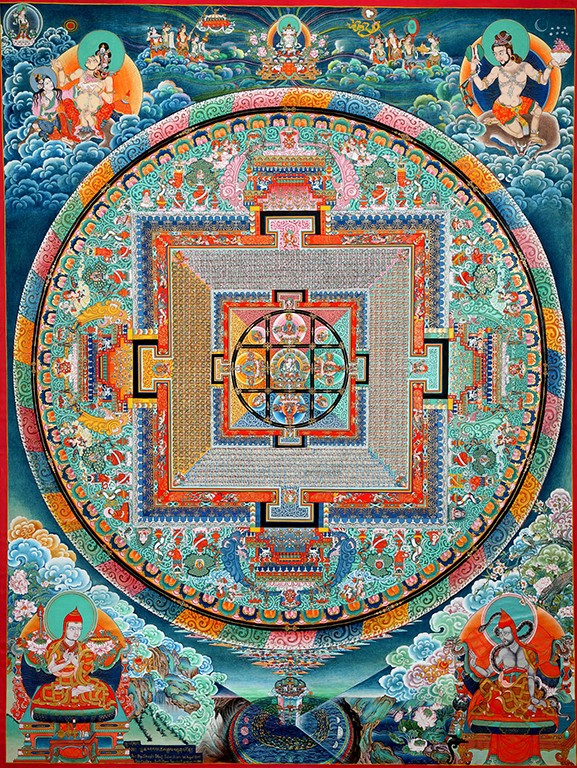

Composite of Vairocana and Vajrasattva Mandalas, 2001-2004

Shashi Dhoj Tulachan (Nepalese, 1942-)

Natural mineral pigments on canvas

L.2012.25.3,.4,.6,.9

Loan courtesy of Gayle and Edward P. Roski |

Returning to a Bowers Near You

For most of the past decade Bowers Museum’s Freedman Galleria has been flanked by nine immense paintings by Lama Shashi Dhoj Tulachan (Nepalese, 1942 -). Though they have been off display for about half a year at this point, our exhibitions team is now preparing to reinstall Sacred Realms: Buddhist Paintings by Shashi Dhoj Tulachan from the Gayle and Edward P. Roski Collection for its reopening on January 27, 2024. The Bowers Blog takes this occasion to share the paintings in more detail than ever before, looking closely at the artist behind the works and the larger tradition in which he works.

|

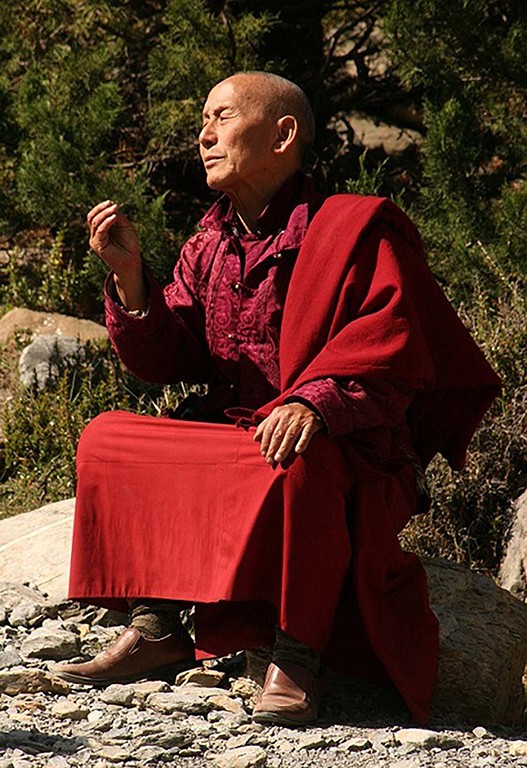

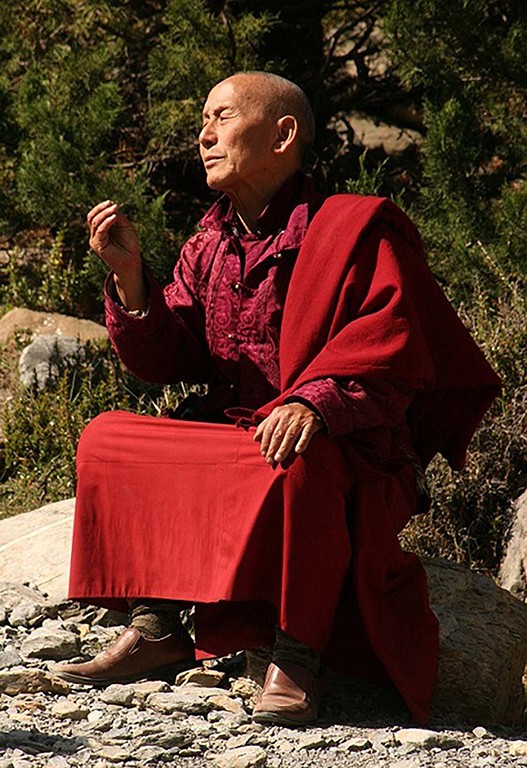

Shashi Dhoj Tulachan, 2013

Photo by Nima t100, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 |

Lama Shashi

Shashi Dhoj Tulachan is a Tibetan Buddhist monk (lama) and second-generation artist specializing in thangka (rolled paintings) and temple murals. Born in Tukuche, a village in Nepal’s Mustang District, he has devoted much of his life to the restoration of Chhairo Gompa, an 18th century Tibetan monastery. For centuries, Buddhist painting in Tibet and the Tibetan Buddhist monasteries of northern Nepal has been practiced by highly trained monks like Tulachan as a way of teaching the tenets of Buddhism. Thangkas are highly portable so that their religious lessons can be shared throughout the mountainous region. Temple murals, often frescoes, are as immobile and awe-inspiring in scale as the monasteries in which they are painted. Tulachan’s works lie somewhere in between the two: they are painted on canvas so that can be easily transported but that are exacted at a grand scale. His nine paintings at the Bowers can be roughly grouped into two categories: works looking at specific devotional figures, in this case Avalokiteśvara and the Four Great Kings, and mandalas. The artist has painted this set of images by combining the traditional motifs of one of the foremost schools recognized by high-level monks in Tibet today, the Tibetan Karma Ghadri School, with novel additions of his own imagining.

|

|

Eleven-Headed, Thousand-Armed Avalokiteśvara (Chenrézig), 1994

Shashi Dhoj Tulachan (Nepalese, 1942-)

Natural mineral pigments on canvas

L.2012.25.1

Loan courtesy of Gayle and Edward P. Roski |

Fractured Facets

Avalokiteśvara, known as Chenrézig in Tibet and Guanyin in China, is the bodhisattva of mercy and compassion. They are depicted in one of their many aspects here as having eleven heads and one thousand arms, each of which has an eye in its palm to witness and ease the suffering of humanity. There are multiple interpretations and proposed origins of this early form of the bodhisattva, but among them is the story of Avalokiteśvara having split into one thousand pieces upon witnessing the suffering of humanity and being put back together in this form by the Amitabha Buddha. This painting is discussed in more detail in Who Answers the Cries: Guanyin at the Bowers.

|

|

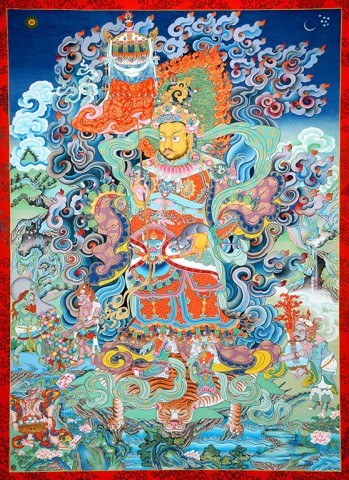

The Four Great Kings, Phakyepo (Virūḍhaka), Yülkhorsung (Dhṛtarāṣṭra), Namthöse (Vaiśravaṇa), and Chenmizang (Virūpākṣa), 1994

Shashi Dhoj Tulachan (Nepalese, 1942-)

Natural mineral pigments on canvas

L.2012.25.8,.5,.2,.7

Loan courtesy of Gayle and Edward P. Roski |

These Four Kings

The Four Great Kings, sometimes referred to as the Four Heavenly Kings or Four Guardians of the World, appear in Buddhist traditions from India to Korea and are said to have been monarchs came upon Siddhārtha Gautama just after he achieved enlightenment as the Sakyamuni Buddha. Their role is to safeguard the dharma—the immutable law of the cosmos—as well as Buddha and his followers. All four live on the slopes of Mount Meru which sits at the center of the Buddhist cosmos; Phakyepo (Virūḍhaka) guards the South, Yülkhorsung (Dhṛtarāṣṭra) the East, Namthöse (Vaiśravaṇa) the North, and Chenmizang (Virūpākṣa) the West. Each figure is associated with a color and a unique iconography that speaks to the abstract concepts and celestial beings that they govern.

|

|

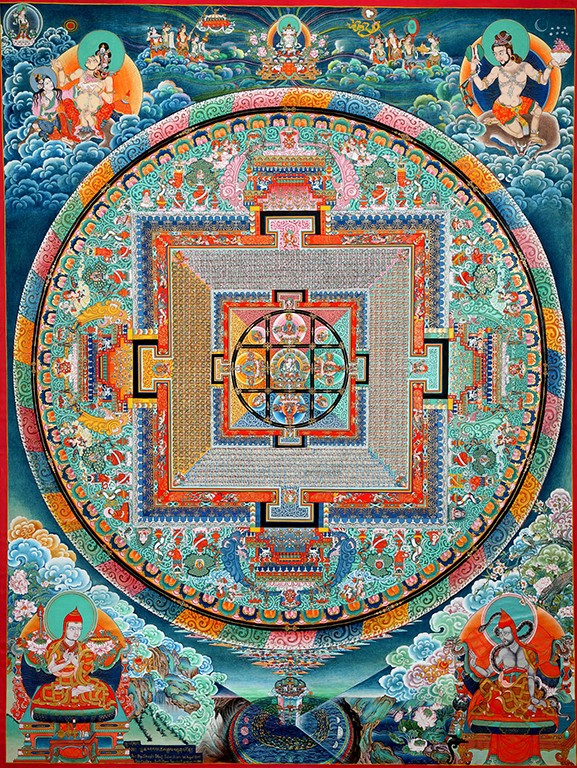

Mandala of Sarvavid Vairocana, 2001

Shashi Dhoj Tulachan (Nepalese, 1942-)

Natural mineral pigments on canvas

L.2012.25.6

Loan courtesy of Gayle and Edward P. Roski |

Circles Within Circles

The concentric geometric forms of mandalas—Sanskrit for “circle”—are models of the cosmos that are used in Buddhism to meditate on various deities. Bordered by a ring of flames that burns away ignorance, they are designed to focus thought on the divine figures at their center and their retinue. The above is a mandala for the four-faced Sarvavid Vairocana Buddha or the “all-knowing Buddha.” In the Brahmajāla Sūtra in which Vairocana is first referenced, he describes himself as being seated on a lotus and surrounded by a thousand Sakyamuni Buddhas from a thousand different worlds, likely what is being depicted with the 1,000 miniature figures that surround Vairocana. The other three mandalas that appear in the exhibition depict different aspects of the bodhisattva Vajrasattva, an important figure associated with purification in Tibetan Buddhism. One of the depictions is his wrathful form, Vajrakilaya. Many Buddhist deities have at least one wrathful form that they can assume to combat demons and other obstacles to enlightenment.

Sacred Realms: Paintings by Shashi Dhoj Tulachan from the Gayle and Edward P. Roski Collection reopens at the Bowers Museum on January 27, 2024.

Text and images may be under copyright. Please contact Collection Department for permission to use. References are available on request. Information subject to change upon further research.

Comments 2

Very beautiful thangkas.

Especially the Vairocana Mandala.

Namaste

considering these paintings are in 'tibetan' style, it would be more relevant to give the tibetan names of deities and the kings than the sanskrit ones