|

Detail of Untitled (Renaissance Man in Garden), c. 1901

Alberta Binford McCloskey (American, 1855-1911)

Oil on canvas; 13 1/2 × 9 1/4 in.

74.22.27

Gift of Mrs. Eleanor Russell |

Galahad to Have You

Romanticized histories have always captured the hearts of those looking to the past. Of all the periods nostalgically viewed through rose-colored lenses, perhaps none is so deceptively attractive as the age of kings and knights. Arthurian legends and tales of brave knights-errant inspire the best in us, even if they were never more than myths. With this weekend’s opening of Knights in Armor, the Bowers is proud to be able to host a collection of over 100 pieces of Medieval, Renaissance, and Medieval Revival arms, armor, and fine art from Florence Italy’s Museo Stibbert. This wonderful collection tells both the true story of the era, but also the importance of its legacy—as seen in its ability to kindle romantic fires in the peoples of centuries since. In a sense, this post picks up where Knights in Armor leaves off. By looking closely at two early 20th Century paintings of subjects in Medieval and Renaissance garb: one by Alberta Binford McCloskey and the other by William Joseph McCloskey, we see how this period continues to attract artists and performers.

|

74.22.27, un-cropepd

Gift of Mrs. Eleanor Russell |

Montague Blues

The first of these two portraits—the painted likeness of a well-frilled man in full Italianate Renaissance garb carefully cleaning his side-sword—was painted by Alberta McCloskey. It is difficult to gauge exactly when this undated work was painted from the content of the painting alone, but solely in terms of portraiture Alberta only came to this degree of mastery late in life, making 1901 a fair estimate. Alberta and William had already separated three years prior. Her entire life, painting had been an inroad to societal status; now as a single parent of two, art was a means of putting food on the table for her family. Who exactly is depicted in this work is something of a mystery. Alberta had painted portraits for actors when she and William lived in New York. This even included a painting of Frederick Paulding as Romeo, a work which would not have looked unlike this one except the principal subject would have been wearing the signature Montague blue instead of this painting’s indeterminate pink. As noted by Nancy Dustin Wall Moure in Partners in Illusion, the best evidence we have is the word “copyright” written in the bottom right corner. It indicates that this work was probably used as an illustration for some now-unknown publication which wanted to draw upon the Renaissance.

|

Untitled (Operatic Heroine in Medieval Dress), 1922

William Joseph McCloskey (American, 1859-1941)

Oil on canvas; 26 1/4 × 21 1/2 in.

74.22.8

Gift of Mrs. Eleanor Russell |

Capulet-à-tête

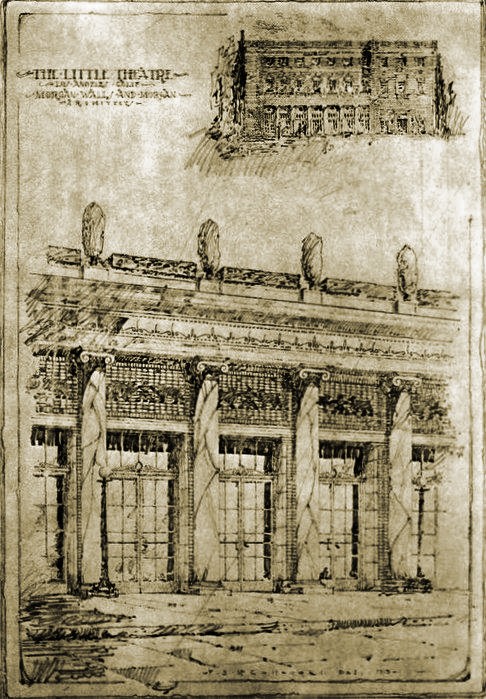

Unlike Alberta’s painting, the year in which William’s portrait of a woman in Medieval dress was painted can easily be established by a series of similar late-life portraits and the physical presence of the number 1922 just below William’s signature. William was often lauded for his ability to capture the essence of his sitter and this painting is no exception. As a classically trained painter in Los Angeles’ flourishing world of film and theater, he was regularly commissioned to paint portraits for actors such as R.D. MacLean. It has been suggested that this is a painting of an actress playing the role of Juliet but there is no real evidence to back up this claim. What we do know from information on the reverse of the painting is that the work was originally exhibited at the Egan School in Los Angeles. The Egan School primarily taught drama, and Shakespearean acting would have been a large component of that. The lack of documentation precludes confirmation, but it is likely that the sitter was one of the Egan School’s fledgling actresses as some Shakespearean character.

|

| Architectural Drawing of the Egan School's Little Theatre, 1912 |

Good Knights

Though it is probable that neither of the paintings featured in this post depict a character from Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, the star-crossed lovers come to mind when discussing William and Alberta McCloskey. The pair that had worked together so well that they fell into an almost indistinguishable joint style eventually discovered that they could not be together. Even separated by an irremediable divide, and likely motivated by entirely different factors, both independently harkened back to the Medieval Period and Renaissance in these paintings. Far from the norm though, knights, the weapons that evolved from those they used, and even the revivals they inspired have remained incredibly pervasive in contemporary culture—something we see in Renaissance Fairs, at dinner theaters like Medieval Times, and in books and film. As these two paintings by the McCloskeys show, fine art has also never abandoned the romantic thread established in the age of kings and knights.

Text and images may be under copyright. Please contact Collection Department for permission to use. References are available on request. Information subject to change upon further research.

Comments 1

Beautiful detail!!