|

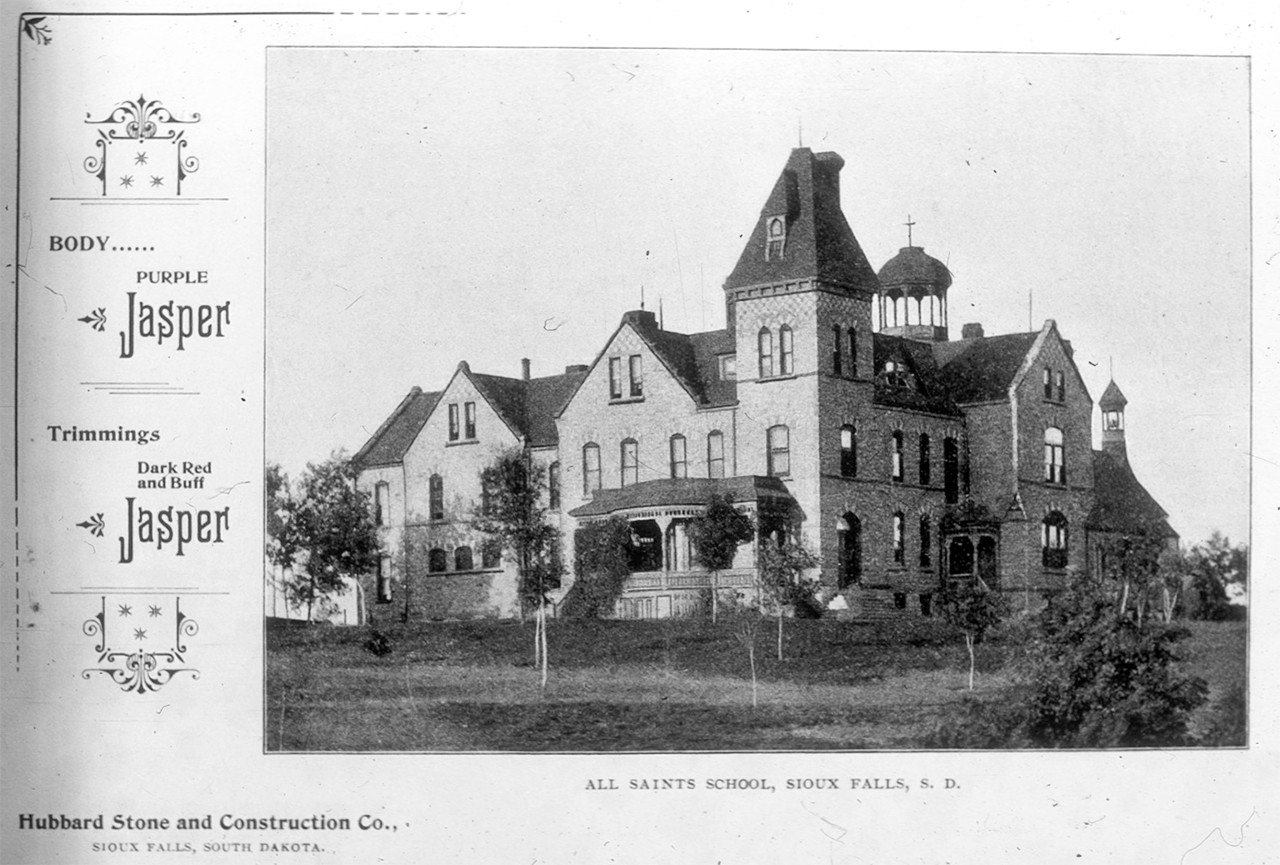

Detail of Lost in the Wood, 1928

May E. Schaetzel (American, 1870-1952); Paris

Gouache on paper; 26 1/4 x 20 3/4 in.

31414

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Jules Schaetzel |

Anticonfluentialism

Uncertainty is the birthplace of anxiety, it is an ailment remedied only by omniscience, and in sufficiently high doses it is suffocating. But it is a boon too. All hope that has ever been kindled—in life after death, that a new town or job might offer something more for one’s family, in a brighter future—is also born of uncertainty. If we accept that subjectivity is an inherent byproduct of art as many scholars do, then uncertainty has been painted into the canvases of every artist from the earliest cave painters to Picasso. The subject of this post is May E. Schaetzel’s Lost in the Wood, a painting as rife with subjective meaning as her life was full of seemingly conflicting information. Here we explore the liminal space between the facts and fiction of Schaetzel’s life, elements that seem to converge in one of the artist’s most unique works.

|

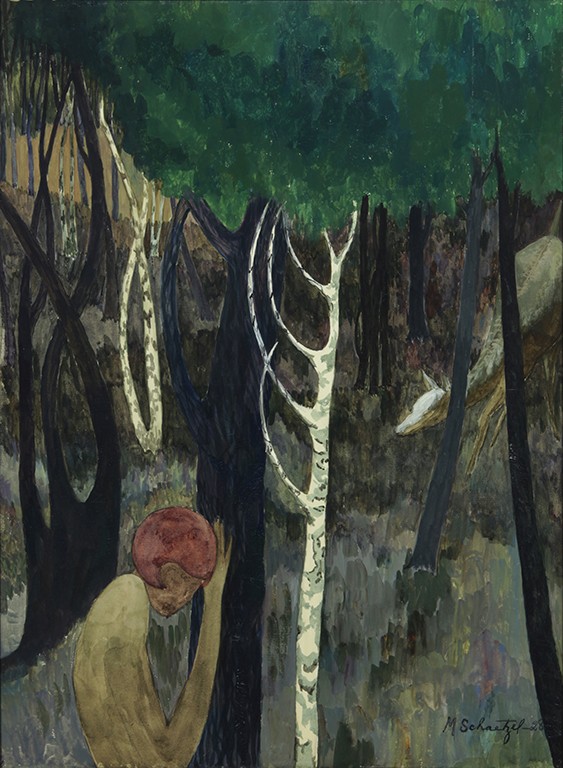

All Saints School, Sioux Falls, c. 1890

Courtesy of the Center for Western Studies, Augustana University |

Et Two Conly, May

Most biographies of May E. Conly Schaetzel, including Edan Hughes’ bible of early Californian artists, Artists in California, 1786-1940, mention her birth in New York City in 1870. Indeed, a May Conly born in New York is living with her family in Brooklyn in 1880. However, a second May Eva Conly born in the far less metropolitan Iowa in 1869 is recorded as living with her family in Elk Point, Dakota Territory—a city of less than 1,000—that same census. In Elk Point, May Conly attended the All Saints School in the nearby Sioux Falls, appearing every so often in local newspapers for her starring roles in school productions. We follow the trail of that second May Conly, because it is she who, in 1890, married the local banker Julius Schaetzel, and took his last name to become May E. Schaetzel.

Their life together seems to have been a blissful one. The wedding itself was described as “One of the happiest social events of the season.” But after spending 17 years together and fathering one son, Julius Griffin Schaetzel, Julius Sr. passed away at 38 years of age. His obituary describes him as a caring, unambitious man who lived “a normal human life” and whose death brought with it “the closing of an average human career.”

|

The Schaetzel Tomb

Courtesy of Find a Grave |

Parisian Getaway

May Schaetzel reappeared in Pasadena in the 1910s, now with an interest in watercolor painting. She participated in shows, she took trips to Hong Kong, and ultimately, between 1920 and 1933, left California to live in New York City, where she worked as a printmaker with Artist Color Proof Associates, and later Europe. She became something of an enigmatic figure, a woman whose listed age fluctuated every time it was recorded. She seems to have almost interchangeably gone by her maiden and married names, and sometimes went by her middle name, Eva, instead of May. In Paris her artworks were displayed at the Château de Fontainebleau, annually at the Grand Palais, and elsewhere. An American journalist she toured through the city described her as being well connected in the arts world and another article states that she was known as the “Window Painter” of Paris for the scenes she painted from her apartment window. In 1933 she returned to Los Angeles and moved into the Claremont Manor where she lived out her days, passing away on January 17, 1952. She is entombed alongside her long since departed husband in Freeport, Illinois.

|

|

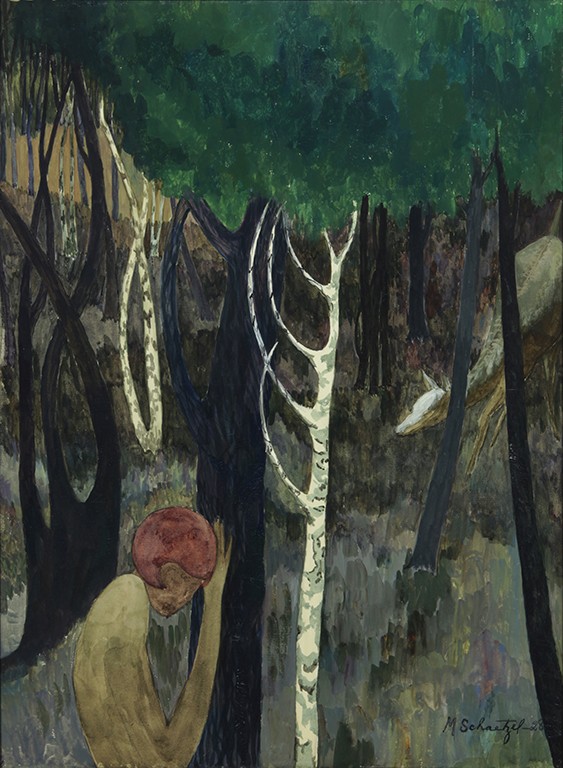

Two floral paintings (photographed in black and white), 1920-1933

May E. Schaetzel (American, 1870-1952); Paris

Watercolor on paper |

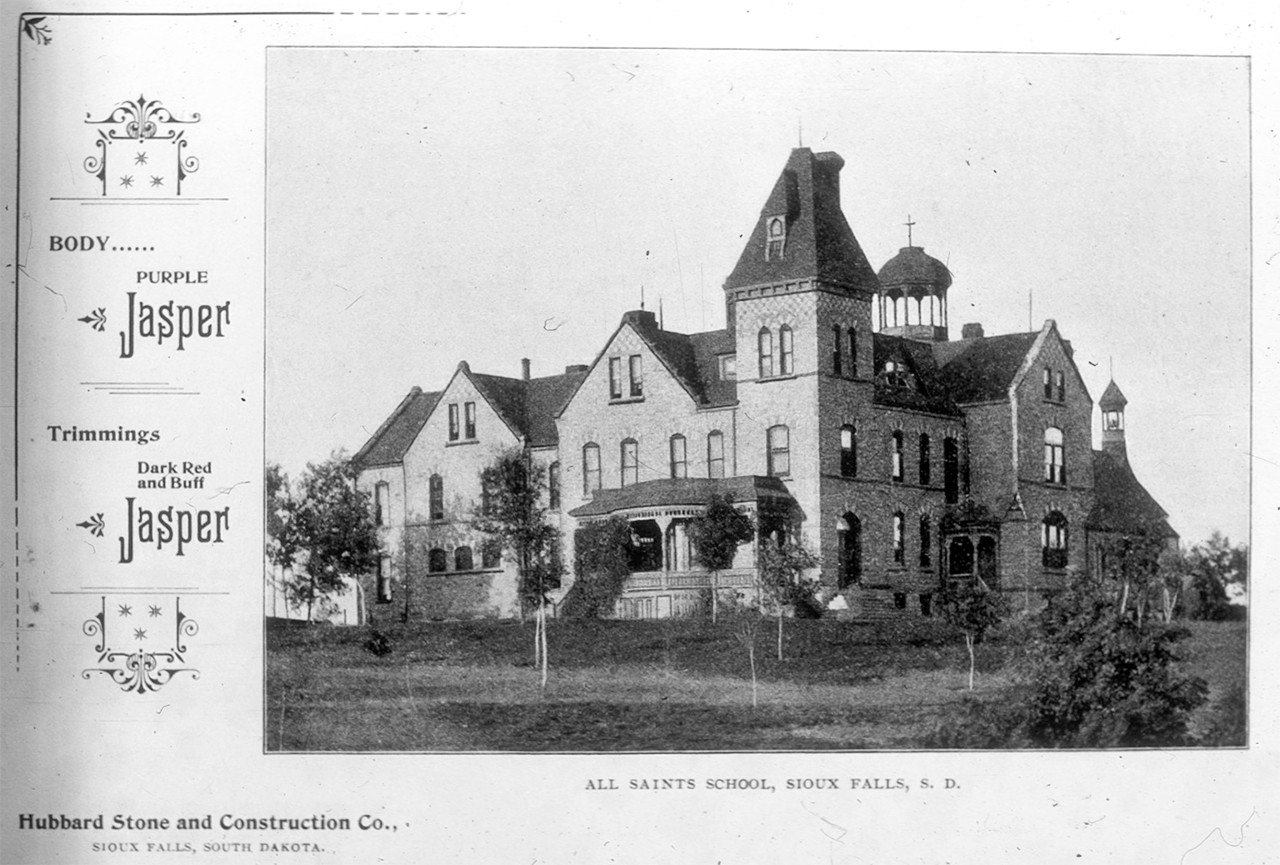

One in Seven

In April of 1966 Julius G. Schaetzel and his wife Hazel donated a group of seven paintings to the Bowers Museum. Of these, six of them were still lifes of flowers, mostly painted as her sobriquet might suggest from the window of her Parisian and Venetian apartments. It is for good reason that biographies of her life describe her almost exclusively as a painter of floral still lives. However, for an artist who is on the record describing her paintings as “joy in the doing,” the seventh painting in the donation, Schaetzel's 1928 watercolor and gouache Lost in the Wood, is entirely perplexing in the larger context of her oeuvre. Its style is distinctly modern, described by a former Bowers curator as Art Deco. In it a white deer cautiously makes its way through the woods in the direction of a woman who hides behind a tree.

|

Lost in the Wood, 1928

May E. Schaetzel (American, 1870-1952); Paris

Gouache on paper; 26 1/4 x 20 3/4 in.

31414

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Jules Schaetzel |

What Dreams May Come

The painting is itself is indeterminate in its apparently rich meaning. The central female figure sports a French bob characteristic of the 1920s and perhaps represents Schaetzel herself. They appear paralyzed though it is unclear whether that is due to their confusing environs, the apparition-like doe seemingly searching them out, or some burden of the mind. Dark trees rise like jailhouse bars up from the earth and bone white birches conjure up images of a skeletal rib cage. Schaetzel’s muted palette only intensifies the dark and mysterious scene. We are left with so many questions. Is it Schaetzel or a character of her imagination, cloaked in the red of her hair as if she had leapt out of a fairy tale and on to her canvas? Is she hiding for her protection or to her detriment? Does the doe represent destruction, purity, salvation, or something else entirely? This painting, like many things in life, is subjective and unknowable. Works like Lost in the Wood might inspire unease, but perhaps more powerfully when we are ourselves feeling uneasy they are reminders that someone else has felt the way that we do. And our burdens are lightened.

Text and images may be under copyright. Please contact Collection Department for permission to use. References are available on request. Information subject to change upon further research.

Comments 1

This piece was an outstanding literary commentary on the theme of uncertainty and its reflection through an artist’s work. We all face uncertainty in so many instances in life and reading this blog caused me to feel much comfort at a time of upheaval in my own life. Mr. Bustamante is to be commended for his excellent writing and creative thoughtfulness in bringing art appreciation to the public while making a connection to one’s personal life. As always this weekly blog brings the Bowers art to life and gives voice to the world’s artists.