|

Crop of Autumnal Tints, 1909

John Francis Murphy (American, 1853-1921)

Oil on canvas; 16 x 22 in.

F7663

Martha C. Stevens Memorial Art Collection |

24 Corot Gold

As of last Friday, we have officially entered fall. Temperatures are at least hypothetically beginning to drop, area foliage is strongly considering a change to yellow, orange, or red—or quitting its branches entirely—and up in Calabazas the pumpkins are stirring from their deep slumber. This week’s post begins an intermittent series on seasonally appropriate scenes in the Bowers permanent collection by looking at John Francis Murphy’s Autumnal Tints. Known as the “American Corot,” a reference to the French Barbizon painter Camille Corot who no one even today would be so bold as to call the “French Murphy,” Murphy was an extraordinarily talented tonalist painter whose work perfectly captures this most-golden of seasons.

|

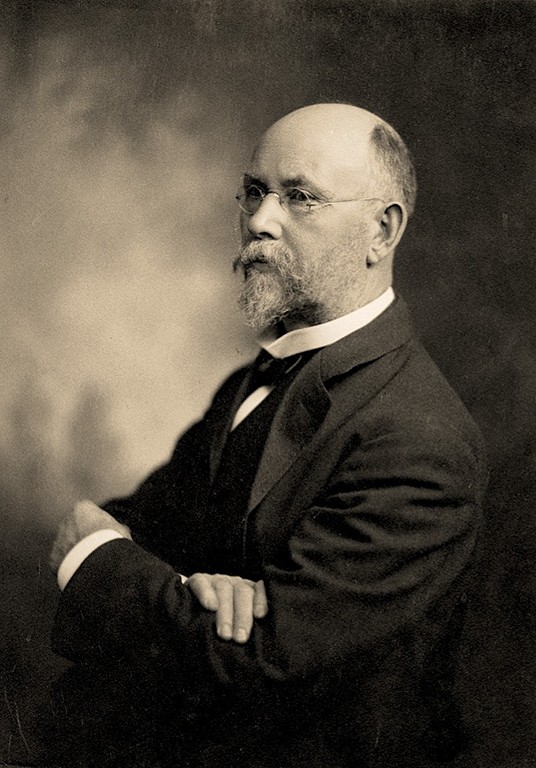

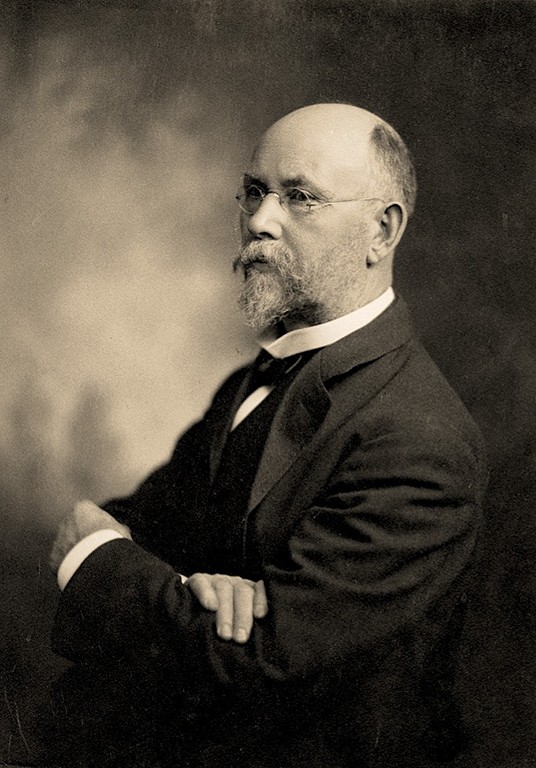

Photograph of John Francis Murphy, c. 1920

Archives of American Art |

Painting to Make Ends Meets

Murphy was born and mostly raised in Oswego, New York in 1853, a city about an hour northwest of Syracuse. In 1868, his family moved to Chicago, and as Murphy entered the job market, he found work as a sign and theater scenery painter. Though he is often described as having no formal training, he did take some classes at the Chicago Academy of Design where he was eventually elected as a member. He saved up his money, and in 1873 he spent three months sketching and traveling through the Adirondack Mountains—a pilgrimage of sorts for a man who had a deep passion for the Hudson River School. A growing dissatisfaction with Chicago ultimately led Murphy to leave the city for New York, where he opened a studio in 1875. He struggled making ends meet, alternatively doing illustration work in the city and boarding with friends in the country—paying them with farm labor. It was not until 1878 and joining the Salmagundi Club that the artist began earning enough of a reputation that gallery doors opened for exhibitions and buyers began to purchase his works.

|

Evening on the River, 1883

George Inness (American, 1825-1894)

Oil on canvas; 33 3/4 x 48 x 3 in.

F7664

Martha C. Stevens Memorial Art Collection |

On Arkville

Though well-liked by his peers, Murphy preferred spending his time surrounded by nature. After he and his wife, Adah Clifford Smith, returned from their first trip to France in 1886—a six-month excursion that included a prolonged stay in the village of Montigny—the couple purchased land in the Catskills and lived there eight months out of every year until he died of pneumonia in 1921. Murphy was one of only a few artists at the time that stayed so close to the wild or human-tamed environments that he depicted in paintings. Part of this was the philosophy of American writers like Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau who championed the inseparable relationship between man and nature and had dug their spurs into Murphy’s psyche at an impressionable age. In the realm of painting, he was playfully ribbed for his similarities to Camille Corot, but in reality drew more from George Inness and similar American tonalists.

|

The Wood Lot, 1914

John Francis Murphy (American, 1853-1921)

Oil on canvas; 25 1/2 × 30 × 2 5/16 in.

F7673

Martha C. Stevens Memorial Art Collection |

|

Untitled, 1881

John Francis Murphy (American, 1853-1921)

Watercolor on paper; 14 x 20 in.

F7716

Martha C. Stevens Memorial Art Collection |

One-Dimensional, And How!

“Although no one can praise Murphy for being a multifaceted landscapist, his innumerable versions of barren, wasted fields and farms have about them a dry, plaintively lyrical quality that continues to endear him to viewers who do not demand more drama or color in their art.”

—Peter Bermingham, American Art in the Barbizon Mood

Much in the same way that almost every pop song relies on the same four chords, Murphy rarely strayed far from his formula, especially once he achieved commercial success in the early 20th century. The Bowers has three paintings by Murphy, one untitled watercolor from 1881, and Autumnal Tints and The Wood Lot which are oils from 1909 and 1914, respectively. While all three share in being nearly monochromatic, a feature of many of his most famous works, the two later paintings are near identical in their palette and composition: a sloped hillside, fallen logs, and a single, prominent tree in the foreground. As is the case with many impressionist painters, Murphy’s forms are indistinct, bleeding into one another as if the viewer was looking through a fogged lens. The gray plaster sky one finds in the Mid Atlantic around this time of year is itself a target to this apparent color bleed, taking on the same blond hue he uses on leaves.

|

F7663

Martha C. Stevens Memorial Art Collection |

Scumbling in the Dark

Murphy began with moderately thick base layers of the overarching hue for his painting, let the paint almost dry, and then scumbled over his work with either a soft or stiff paste. He made the forms of trees by applying a thin, soft paste and added details such as tree branches with thick fluid paint. The uneven application of paint used with Murphy’s process led to the wonderfully textured surface of the work, the lighter portions of which are almost reminiscent of stucco.

Text and images may be under copyright. Please contact Collection Department for permission to use. References are available on request. Information subject to change upon further research.

Comments