|

| Artist's rendition of 2004.66.1.1-.2 and 31901 in dialogue in a futuristic setting. |

Man: The Lore (ian)

This coming Monday marks yet another May the Fourth (be with you) on the Galactic Standard Calendar. While it might be an unremarkable day for the least nerdy of us, for those of us raised on Star Wars the date is as sacred as the Jedi texts. And what a year it has been for the franchise: its first live action television show was a must-watch hit, baby Yoda force melted the hearts of millions, and the final film in its trilogy of trilogies was released. The epic saga can be characterized a great many ways, but you must hand it to George Lucas and others, they have never once shied away from characters—especially male members of the Skywalker clan—losing their limbs. Across the 9 movies there are at least 13 instances of named characters losing hands and arms, and that number only goes up when extended to legs and essential body parts. This post draws upon the Bowers’ cultural art from around the world to pay homage to one of the most important American cultural icons of the 20th and 21st centuries: Star Wars. In it we compare the trials of quintessential Star Wars characters like Luke, Anakin and the beloved, abominable Wampa to sculptures which were made with two arms and lost at least one of them before being donated to the Bowers, as well as some of our hand-shaped objects.

“That’s what happens when you play with swords.”

George Lucas

|

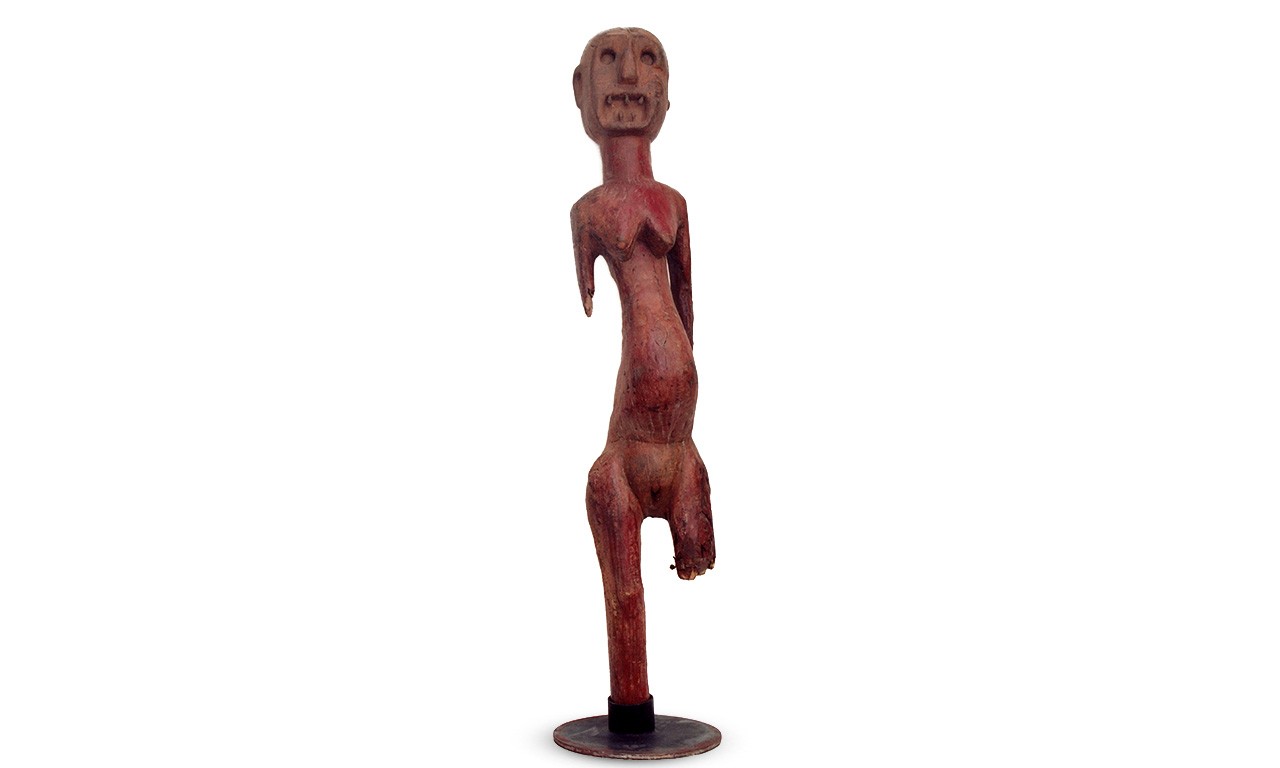

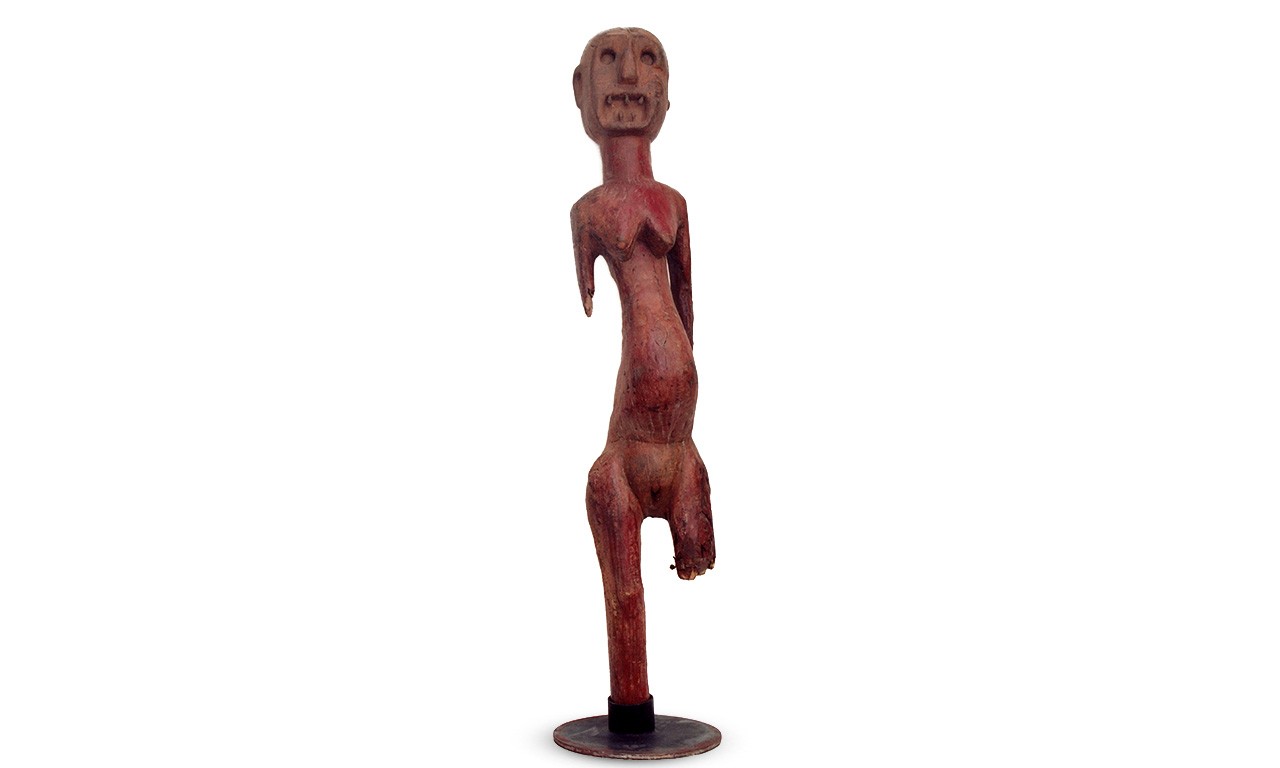

Standing Female Figure; 16th to 19th Century

Dogon culture; Niogom, Mali

Wood; 71 x 11 in.

2003.34.6

Gift of Harry Rady |

Mustafar from Home

Now reminiscent of a lava-singed Anakin after he bravely defied Obi Wan Kenobi’s advice, “I have the high ground… don’t try it,” this wooden sculpture was made by the Dogon culture of Mali. Dogon sculpture mostly depicts religious themes, ancestral figures or horsemen. Figures such as this were typically kept at shrines or in the house of the Hogon, the head of the village, until they were brought out for funerals.

|

Female Figure, c. 1880

Yuma culture; Arizona

Clay, pigment, wool cloth, glass bead and reed; 7 1/4 x 2 5/8 x 1 3/4 in.

86.17.14

Gift of Julia Rounds Calborn and Chase Childs Calborn |

Fair at the Fair

Yuma dolls of painted pottery resemble prehistoric Hokokam clay figurines and suggest a link between the modern and prehistoric peoples of the desert. The facial tattooing identifies this doll as a young, beautiful Yuma girl. It is not clear when or how this figure’s arm would have been damaged, but it was originally exhibited at the 1893 Chicago World's Fair with both limbs attached.

|

Cast From the Hand of Evylena Nunn Miller, mid 20th Century

Evylena Nunn Miller (American, 1888-1966)

Plaster cast; 5 x 7 1/2 in.

31901

Evylena Nunn Miller Memorial Collection |

Evylena’s Digits

The many hands and handless figures in this post were all made with some degree of stylization, the one exception to this being this incredibly lifelike plaster cast of Evylena Nunn Miller’s right mitt. Rather than the creation of this unattached hand being the result of a disagreement with her father on the floating cloud city of Bespin, this plaster cast forever enshrining the painter’s hand was made sometime in the last few decades of her life.

|

Figure of Nefertum, c. 525 BCE

Egypt

Bronze; 2 1/2 x 1 1/4 in.

79.55.11

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Richard and Marilyn McCarthy |

The Chosen One

This is a small bronze figure of Nefertum, an Egyptian deity who is said to have risen from the primordial waters with a lotus on his head. He was a symbol of the rising sun and regeneration, and though regenerative power in Egypt was much more associated with the day and night cycle, he would likely have been a patron god of force healing had he only been worshiped in the Star Wars universe. The bronze that this figure is made from is naturally resistant to corrosion, but the arm was likely separated due to natural decay in the two and a half thousand years since its manufacture.

|

Picks, 19th Century

Unknown Artist (American); North America

Sperm whale ivory and metal

2011.25.88.1-.3

Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Burton W. Fink |

Hand Picked Selection

Much like how a very young Anakin carved a charm for Padme out of a japor snippet he happened to have lying around, 19th Century New England whalers used whale teeth and bones to create art. Scrimshaw was shaped into every form imaginable to the mind of sailors, but carvings on the high seas often relied on source materials available on ships. Fortunately, the inspiration for this design was close at hand.

|

Sculpture of a Woman (Minqi), Han Dynasty (206 BCE-221 CE)

China

Terracotta; 13 1/4 x 21 1/2 in.

2004.66.1.1

Gift of Mr. Dennis J. Aigner |

3,000 Count

Minqi or spirit goods are clay figures which were placed in great numbers in Chinese tombs during and following the Han dynasty. Originally these figures were intended to capture the likeness of an emperor’s attendants and allowed these servants to follow rulers into the afterlife without human sacrifice. Made using molds, both the head and the hands of this sculpture were articulated. Unlike Count Dooku, this figure is fortunate to have only lost its hands.

|

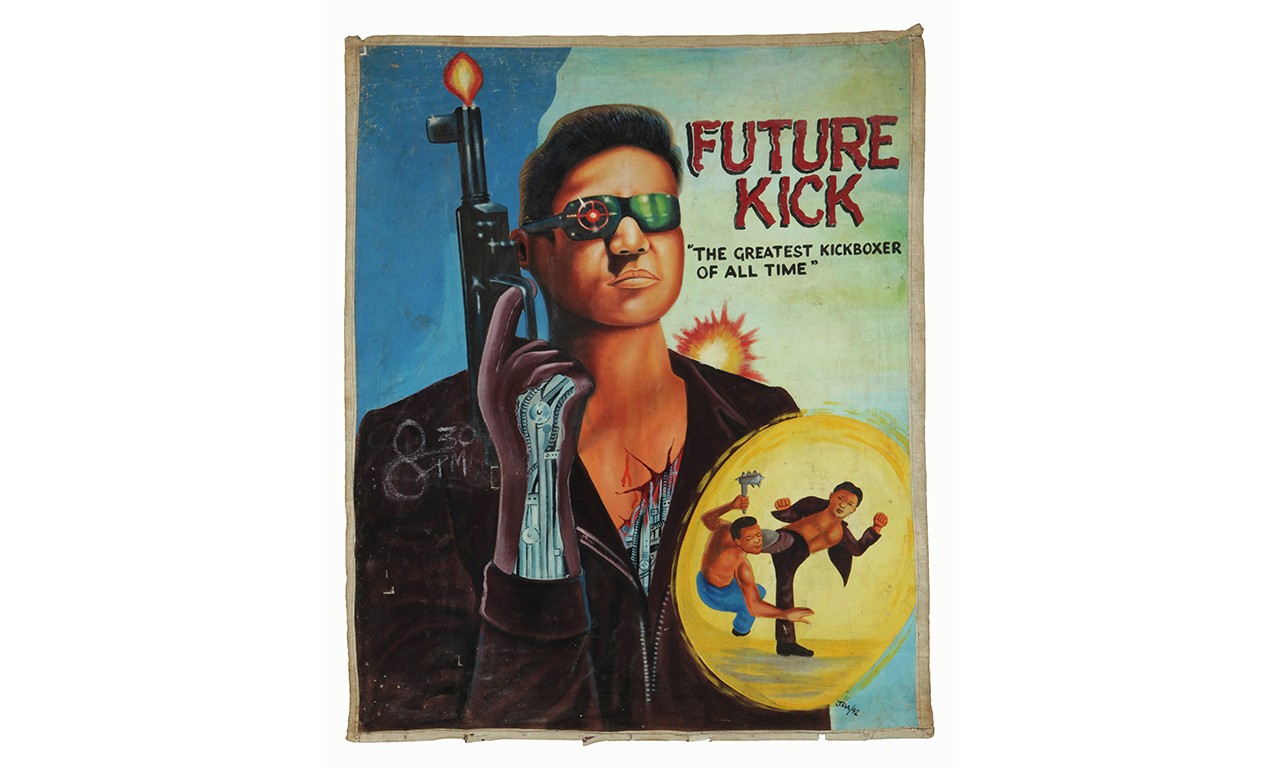

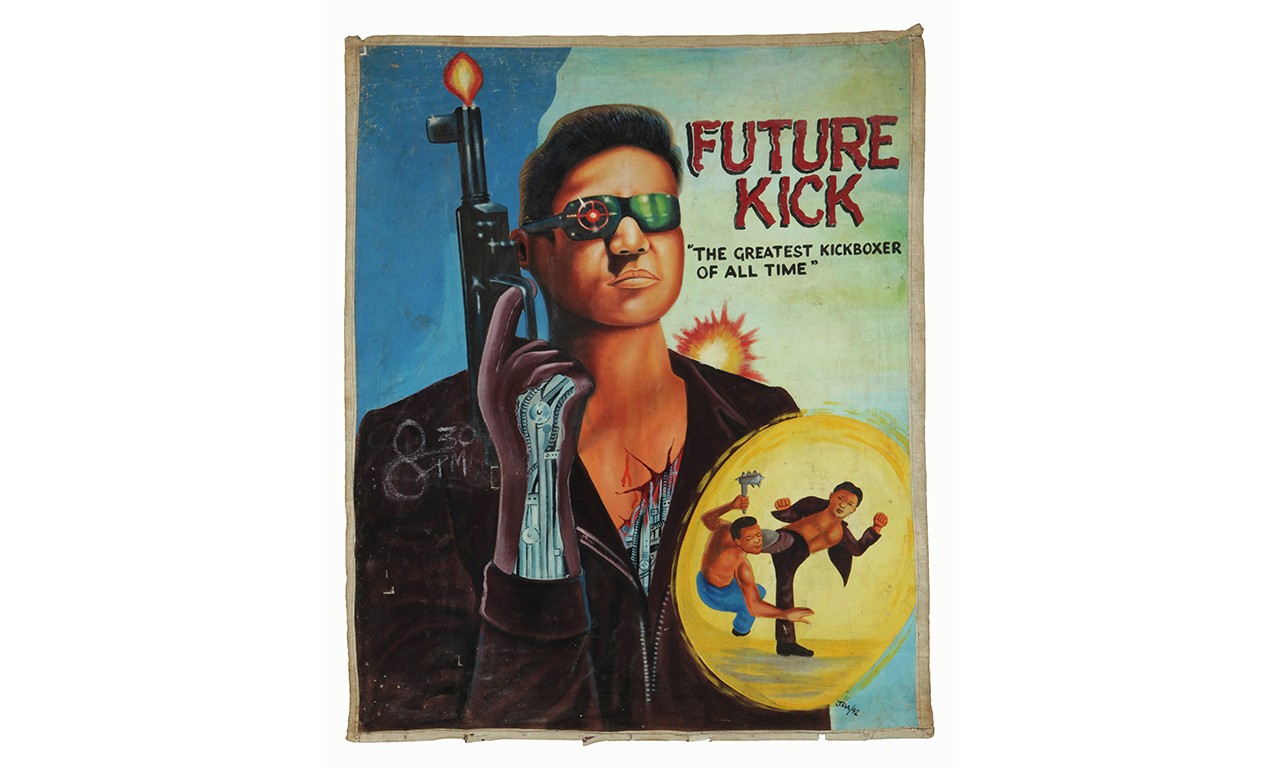

Future Kick, 1992

Jam (Ghanaian)

Oil on cotton canvas; 56 × 47 in.

2014.28.31

Gift of Jay and Helen Lavely |

Bacta The Future Kick

Few objects in the Bowers’ collections are more iconic than the wonderfully over-the-top action film posters from Ghana. Future Kick stars the legendary kickboxer Don ‘The Dragon’ Wilson in the role of, you guessed it, a cyborg version of Don Wilson. Now, while the character may not have had any one body part robbed from him by a Sith lord, the poster clearly shows his hand to be every bit as cybernetic as Luke Skywalker’s.

Text and images may be under copyright. Please contact Collection Department for permission to use. Information subject to change upon further research.

Comments