|

Helmet "Firespitter" Mask (Kponyugu), early to mid 20th century

Unrecorded artist, Senufo culture; probably Côte d'Ivoire

Wood; 40 x 15 x 14 1/2 in.

2022.8.11

Gift of Diane M. Conn in Memory of Mace Neufeld |

Passing On

Cultures from around the world have found many different answers to the question of what happens when we die. In some versions of the belief system of the Senufo people of Mali, Côte d'Ivoire, and Burkina Faso, death is an eternity of haunting the mortal plane for those that are not sent to the afterlife through proper funerary rites. The helmet masks featured here, alternatively called firespitters or, in Senufo vernacular, kponyugu, are worn by initiated members of the Senufo’s poro or lô society on several occasions but especially at funerals to help the deceased’s spirit to pass on to the realm of the ancestors without issue. This post looks closely at the purpose, production, symbology, and use of two such masks in the Bowers Museum’s permanent collection.

|

Helmet "Firespitter" Mask (Kponyugu), mid to late 20th Century

Senufo people; Ivory Coast

Wood and pigment; 15 1/8 x 12 1/4 x 27 7/8 in.

2002.59.3

Gift of James Carona |

Lô and Behold

The poro society is very much still central to Senufo religion and society. Like many secret societies, poro can only be joined by males and involves separate initiation levels that are broadly divided into categories for young boys, adolescents, men, and the elders that make most important community decisions. Religious knowledge is protected among the highest ranks of the society. To this day about half of Senufo people subscribe to the traditional animistic beliefs of poro with a sizable portion of Senufo-speaking peoples having converted to Islam and a much smaller percentage having converted to Christianity. Whether or not they have converted, Senufo peoples as a whole have taken great steps to ensure that their culture will live on through the continued practice of traditional dances at festivals and the promotion of arts such as the wood carving of these masks.

Carving Faces

Senufo wood carvers customarily occupied a unique position distinct from that of farmers and other artisans. Though they were still required to handle the farming of their own lands, they were seen as being in a class of their own, a distinction further compounded by their being in a slightly modified version of the poro society that allowed one to more rapidly pass through initiation ranks and thus earn the skills and religious knowledge required to create these masks. Most sculpting and mask-making work is down with an adze and knife while wood is still green so that it is easier to work. Specific to large masks such as this, carvers use a soft wood of the genus Bombax. To add polish and patina, rough leaves are used for sanding and then butter or oil is applied in combination with smoking the wood. The presence of pigments tend to be characteristic of more recent masks.

|

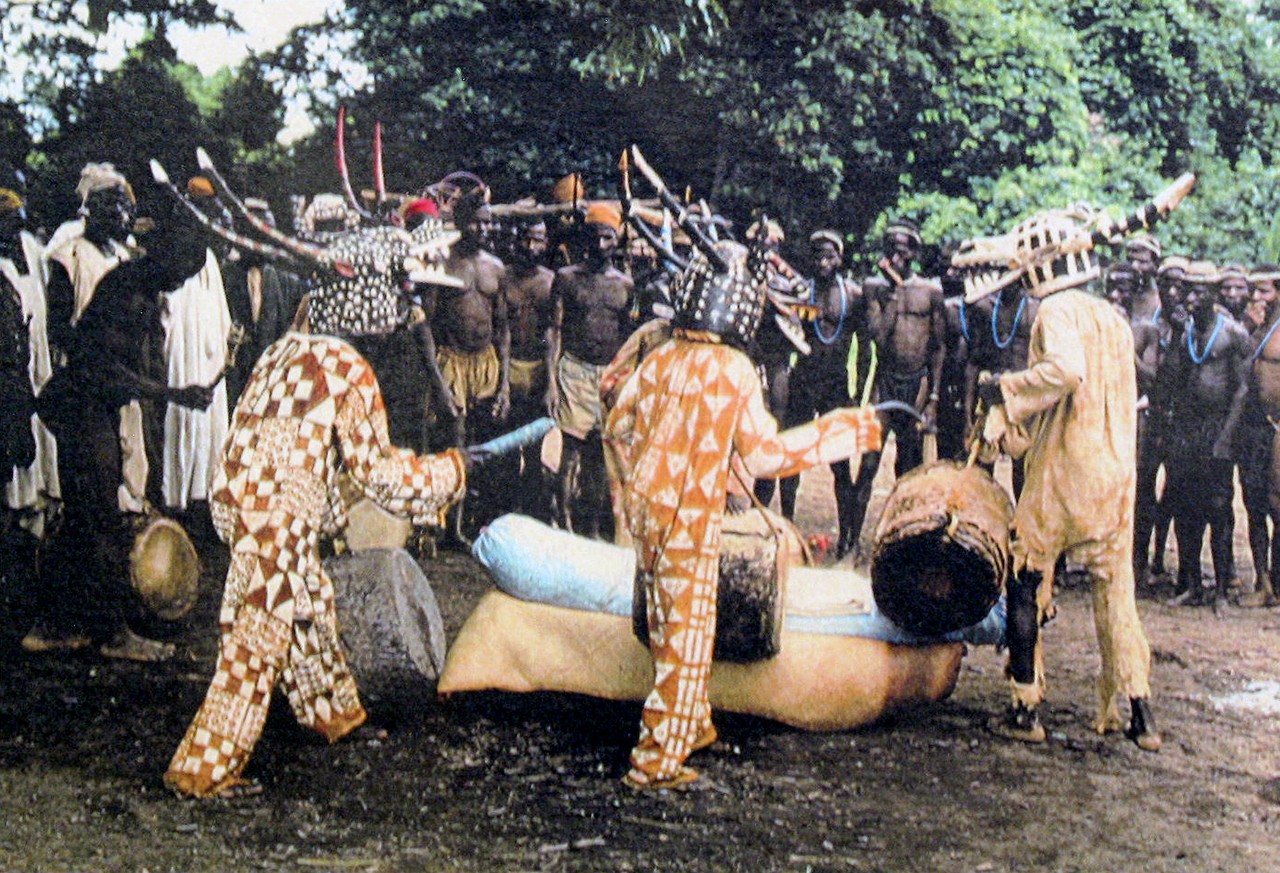

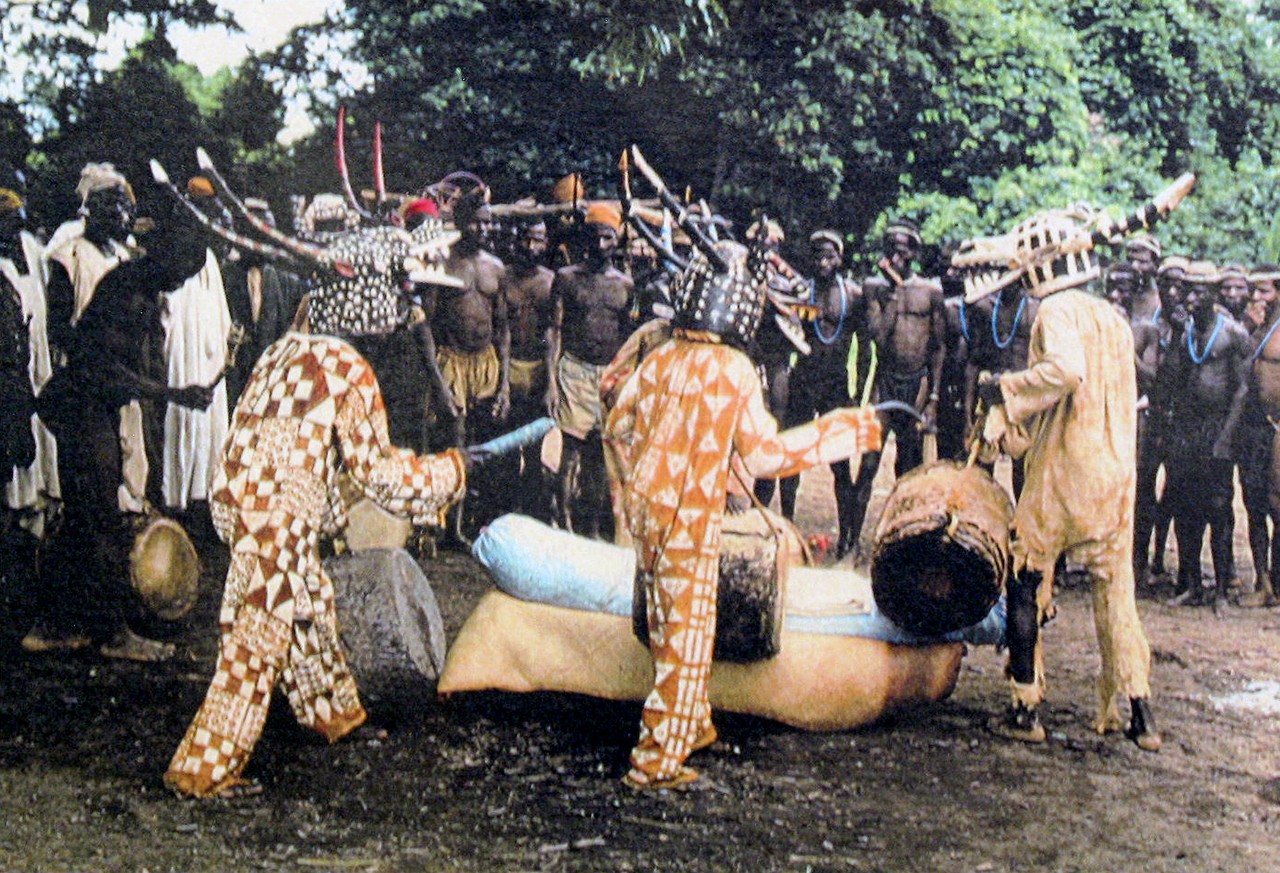

| Poro members wearing kponyugu masks at a funeral, Dikodougou district, Ivory Coast, photograph by Anita Glaze, 1970 |

Chimeric Headwear

Helmet masks or kponyugu are more than the sum of their individual zoomorphic parts. Their dynamic and intentionally frightening forms can be broken down into various elements such as the horns of an antelope, the tusks of a warthog, and the mouth of a crocodile or hyena. Each of these animals are important symbols to the Senufo representing traits connected to the creation of the world such as strength and fertility; however, the combination of elements in a kponyugu is a demonic form that is danced at funerals by high-ranking poro initiates to scare away evil spirits. The different subcategories of mask also each take on different nuanced interpretations. For example, the cup supported by a chameleon and hornbill on the newer of the two Bowers masks makes it a subtype called waniougo and is representative of the connection between humanity and the ancestral plane. This further supports the use of this mask in funerals as the deceased are often beseeched before passing on to relay messages to ancestors. It should be stressed that because poro societies are organized on a village-level there is no one uniform set of beliefs and related practices that applies to all Senufo. There are many conflicting sources about the exact nature and importance of the connection between these masks and funerals. In some versions kponyugu protect the soul of the deceased from evil spirits, in other cases the soul of the deceased risks becoming evil by remaining in villages and must be scared away so that it finds its way to the realm of the ancestors.

|

Alternate view of 2022.8.11

Gift of Diane M. Conn in Memory of Mace Neufeld |

Flames in the Night

Perhaps the most visually remarkable aspect of kponyugu is that which earns them their colloquial name of firespitter. A mixture of grass and a resin that is used regionally for torches is inserted into the toothed maw. Using a hole in the mouth of the chimeric mask, the wearer blows hard on a concealed, smoldering piece of ashen wood to ignite and expel the mixture as a blaze of flames and sparks. Though it is widely discussed, experts do not have a satisfactory answer as to how the flammable mixture is intermittently used for periods of up to 30 minutes without igniting the raffia bodysuits that are often worn in conjunction with kponyugu.

Text and images may be under copyright. Please contact Collection Department for permission to use. Information subject to change upon further research.

Comments