|

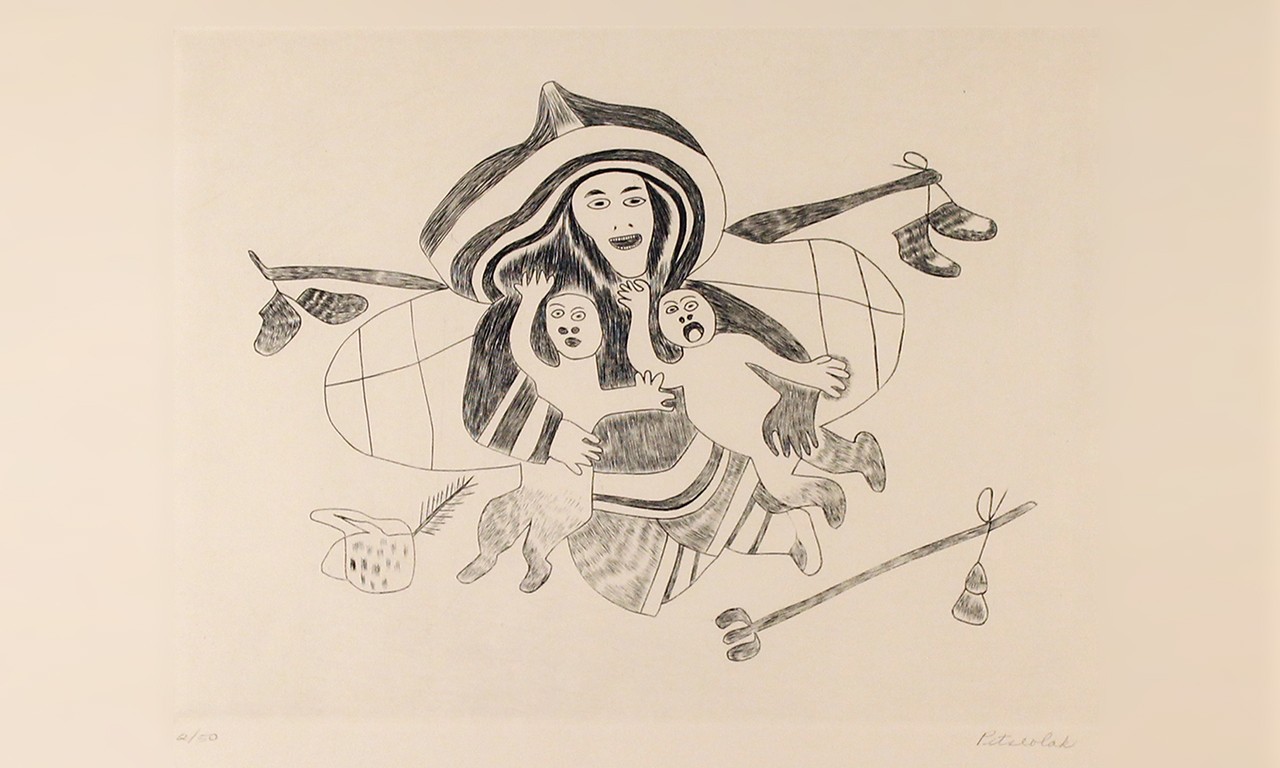

Untitled (Woman with Two Changelings), 1962

Pitseolak Ashoona (Inuit, 1904-1983); Cape Dorset, Nunavut Territory, Canada

Engraving on paper; 17 3/4 × 23 1/2 × 5/8 in.

2013.8.6

Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Burton W. Fink |

National Native American Heritage Month

The rapid technological advances of the 20th century presented more change than any other in human history, and either directly or indirectly jeopardized the arts of many of the Indigenous cultures of North America. As utilitarian objects like vessels were replaced by cheaper western alternatives and traditional mediums like whale teeth and bone became ever scarcer, many Native Peoples turned to various artforms to create lasting records of their traditional ways and to support themselves financially. This post explores the birth of printmaking within the Inuit culture and looks at three artists who were among the first to create graphic works.

Co-Op Mode

The Inuit people have lived in what is now northern Canada, Alaska and Greenland for at least the past thousand years, and evidence shows that they broke off from a larger migration of peoples into the Americas approximately three thousand years before that. There is a long graphic tradition among the Inuit, which took the form of carvings on ivory, tooth, and horn. In the 1950s, the same James Houston that was responsible for creating an industry around soapstone carving started a print shop in Cape Dorset, a hamlet located just off the southern tip of Baffin Island. Using the drawings of Inuit artists, Houston worked with Osuitok Ipeelee and Kananginak Pootoogook to create a series of prints using extra pieces of linoleum as a relief material. After more experimentation and several ingenious solutions to working with almost no materials—lithographs made using soapstone and stencils cut from sealskin are two examples—they had built a small collection of prints. Houston arranged for the prints to be exhibited in Winnipeg and Stratford, and they were extremely well received, selling out in short order. Building on to their success, the artists formed the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative to ensure that the bulk of the profits from their work would return to them and their community. The co-op continues to serve the same role to this day.

|

| West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative artists and printers, 1961. Pitseolak Ashoona in rear left. |

Pitseolak Ashoona

The earliest of the three prints made by Inuit artists in the Bowers collections was drawn by Pitseolak Ashoona, one of the foremost Inuit artists to create drawings on paper for the purpose of having them turned into prints. She was born in 1904 and spent much of her youth living a traditional semi-nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyle on southern Baffin Island, mothering 17 children. Sometime in the late 1950s or early ’60s she moved to the area around Cape Dorset and began to draw without any formal training. Her works depict scenes recalled from her youth and mythological stories that had formerly been passed down orally and in carvings. By the time she passed away in 1983 she had created between eight and nine thousand drawings, many of which had been sold in their own right or made into prints. To this day, she has an international reputation as a trailblazer and qaujimajatuqangit, an Inuit word for someone who guards tradition. This untitled work shows a woman with two children and may reference an Inuit myth about a woman who gives birth to changelings.

|

Kidnapping, 1969

Helen Kalvak (Inuit, 1901-1984); Ulukhaktok, Northwest Territories, Canada

Stonecut on paper; 24 1/4 × 29 5/8 × 1 in.

2013.8.16

Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Burton W. Fink |

Helen Kalvak

Unlike Ashoona, who worked with the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative, Helen Kalvak was one of the first Inuit artists associated with a similar printing co-op that was established in modern-day Ulukhaktok on Victoria Island. She was one of five artists who created a group of 30 prints for publication in the Holman Eskimo Co-operative’s first collection. As a child she had been trained to become a shaman. As a result, many of her works speak to this early spiritual connection and incorporate mythological and transformational themes. This work, titled Kidnapping, appears to depict Qalupalik, a mythological woman wearing the traditional clothing of a new mother who steals errant children from their parents.

|

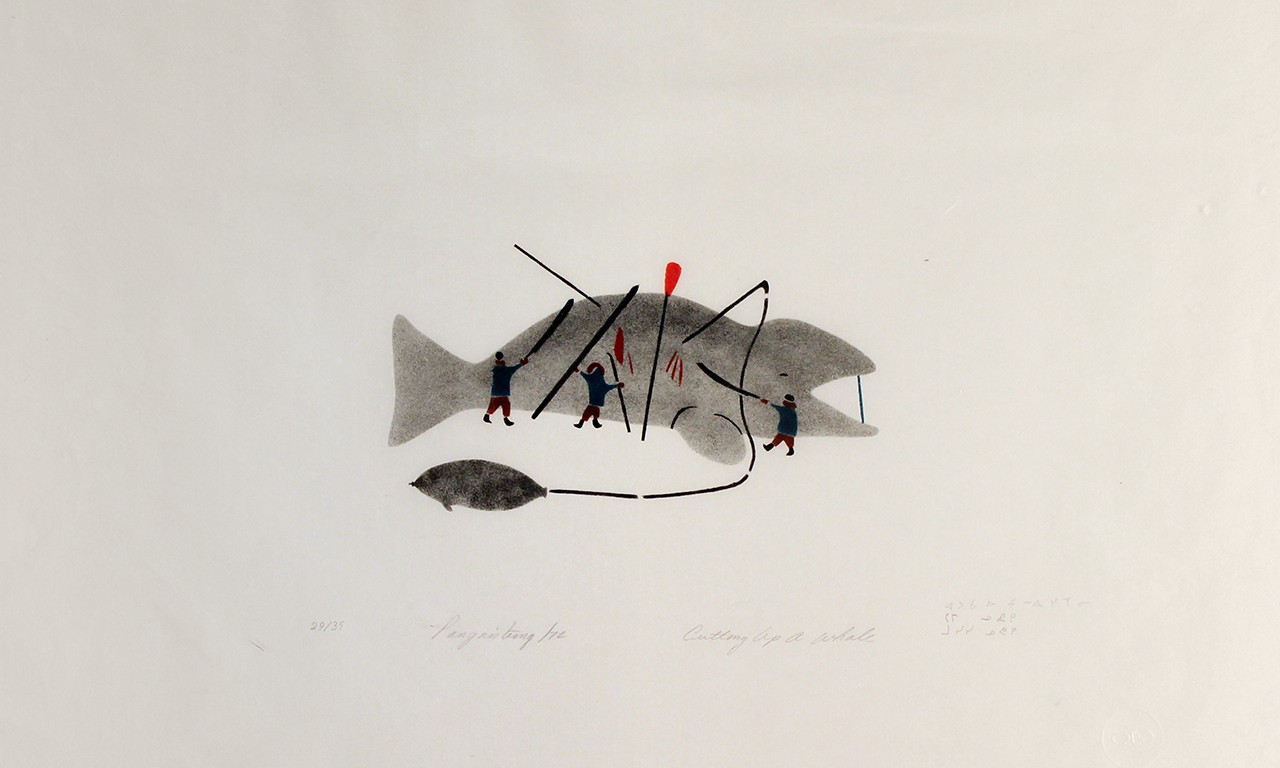

Cutting Up a Whale, 1973

Atungauyak Eeseemailee (Inuit, 1923-1989); Pangnirtung, Nunavut Territory, Canada

Stencil on paper; 17 1/4 × 24 7/8 × 1 5/16 in.

2013.8.2

Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Burton W. Fink |

Atungauyak Eeseemailee

Little is known about the last of the three artists to have created drawings for the Inuit prints in the Bowers collections, except that she worked with a third printing workshop which was established in Pangnirtung in 1969 with support from the Canadian government. Cutting Up a Whale was among the workshop’s first run of prints, published in 1973, and it was from an edition of only 39 prints. Like much of the Inuit art produced during the middle of the 20th century, it speaks to lost lifestyle of the Inuit prior to mandatory acculturation and sedentarization. It depicts a large grey whale that has been harpooned with three men in parkas just beginning the long work of processing every part of it.

Text and images may be under copyright. Please contact Collection Department for permission to use. References are available on request. Information subject to change upon further research.

Comments