|

Miniature Painting and Easel, 20th Century

Possibly Claire M. Doret (Swiss-born American, 1887-1982)

Oil on canvas and wood; 6 x 4 in.

99.36.33.1,.7

Gift of Mrs. Katherine Hotchkiss |

Small World After All

With some of the Bowers Museum’s most impressive objects unarguably being the largest, it can be all too easy to let smaller objects in the collections slip through the proverbial cracks. However, over 5,000 years before miniaturization became a buzz word of the ‘00s, small sculptures of objects, animals, servants and more were made by ancient Egyptians so that they could be taken to the afterlife. Tiny versions of objects appear in most of the cultures of the world, often enjoyed as curios, children’s toys, and portable versions of larger objects. This post looks at some of the greatest Bowers objects that could fit in the palm of your hand and at some of the ways in which miniatures have historically been used.

|

Though this violin and bow have since been deaccessioned, this is a prime example of the kind of doll accessories in the Bowers Museum's collections.

R.2001.14.41 |

Doll-drums

Perhaps the two largest groups of miniature objects are toys made for children and models made for hobbyists. Given the substantial number of dolls and model trains in the collection, it is no surprise that the Bowers should have corresponding accessories and scenery. Were someone to take a census of the museum they would find that dolls outnumber staff about 30:1, and that there are almost 500 doll-sized accessories ranging from auxiliary hairpieces to toothbrush holders, naturally, dollhouses are comfortably nested in that spectrum.

|

Walnut Gem Case, 20th Century

Possibly Claire M. Doret (Swiss-born American, 1887-1982)

Walnut, metal and gemstones; 1 3/4 x 1 3/4 in.

99.36.13.1

Gift of Mrs. Katherine Hotchkiss |

CDT Do Little

There are a few important names in terms of the miniatures in the Bowers Museum’s collections, but the most significant of these is almost certainly Claire M. Doret, whose compact collections and creations have been featured in not one, but two posts on the blog. As an inventor, artist and dental technician who spent much of her time examining things through magnifying lenses, Doret developed an interest in miniatures. She was a talented artist who made objects like her replica Tutankhamun sarcophagus and she also had a bad case of the collecting bug. The miniature painting and easel featured at the top of this post and this receptacle for gemstones housed in a walnut shell were either made or acquired by her as parts of a larger collection of miniatures which could have furnished the homes of perhaps two to three garden gnomes but were instead once proudly displayed in a cabinet of miniatures.

|

Miniature Samovar, c. 1970

Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

Silver; 5 1/2 x 4 7/8 x 4 in.

77.4.13

Gift of United States Government |

Samovar Over the Rainbow

Doret’s miniature objects are not the only ones to have been featured in a recent blog post. This samovar was mentioned in a post on gifts of state given to the Bowers Museum in the 1970s. The tiny tea maker stands at just over 5 inches and despite appearing to be a toy is fully capable of its duties as a samovar given an external heat source. Though this object was used for diplomacy, miniatures of objects featured in museums and other historic sites are commonly sighted in gift shops. Even the Bowers Museum’s gallery store has a miniature version of a permanent object on display in the museum.

|

Two, Two-Spouted Vessels, 20th Century

Acoma style; Southwest United States

Painted ceramic

2003.30.114 and 2004.41.2

Gifts of Mr. and Mrs. George T. Butler and Armand J. Labbé |

Fistful of Ollas

Much in the same way that the samovar would have originally been sold to tourists at the home of Leo Tolstoy, this collection of some 427 miniature pottery vessels were slowly collected from roadside gift shops throughout the American Southwest sometime between 1940 and 1960. Created by the same Native American potters who created the full-sized vessels they are photographed with; these delightfully adorable made-for-sale minis were ideal ways of earning more revenue while using less clay than ever before. Many of these miniatures fully retain the features of their larger antecedents, including intricate designs and variable textures caused by using different glazes. The smallest of these vessels is woven rather than ceramic and is about half the size of a dime.

|

|

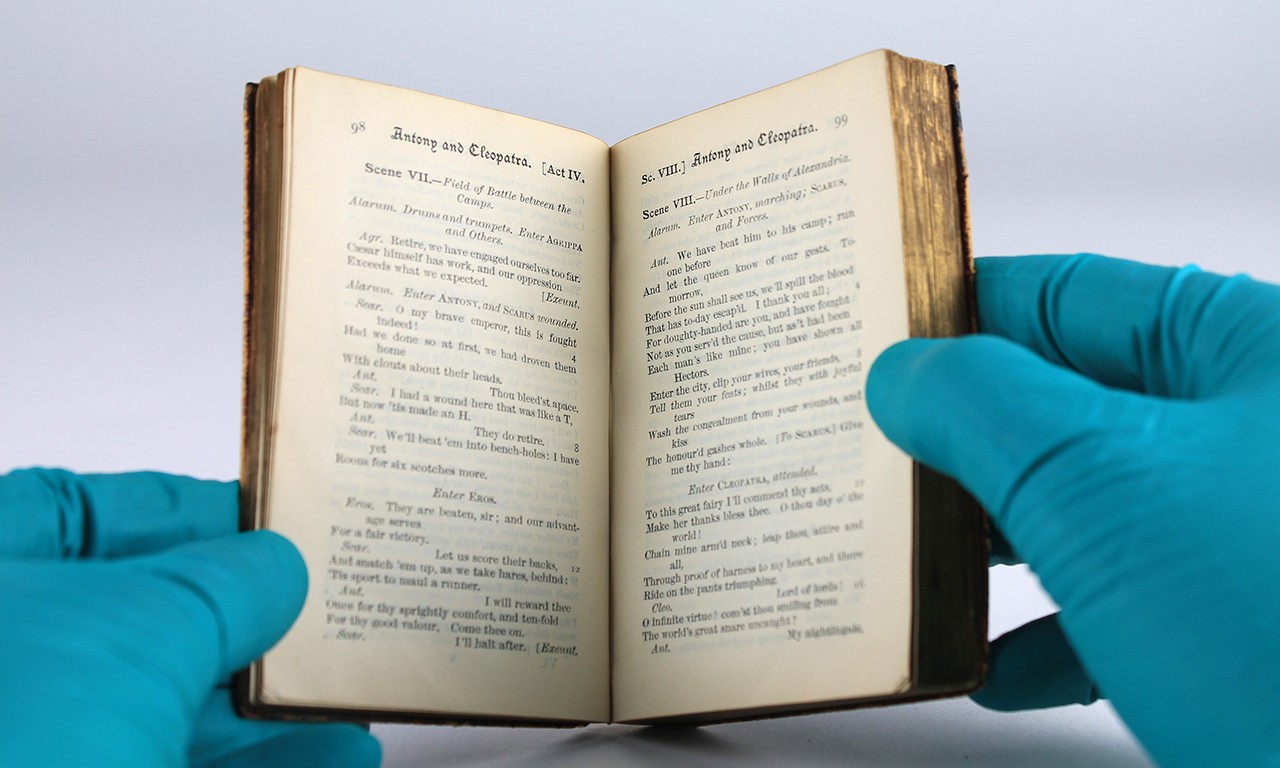

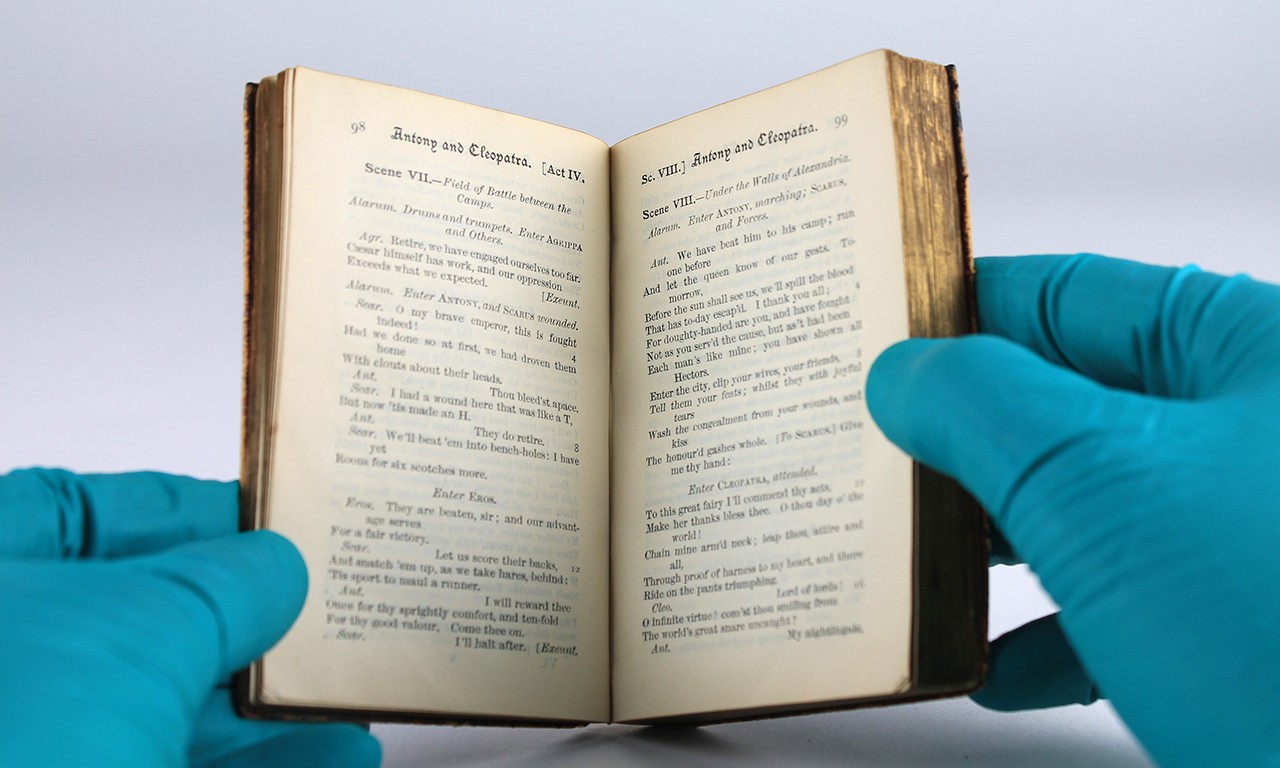

The Oxford Miniature Shakespeare, Volume VI, early 20th Century

William Shakespeare (English, 1564-1616)

Published by Oxford University Press; London, England

Leather, paper and ink; 4 1/4 × 2 3/4 × 1/4 in.

2015.13.5

Estate of Mrs. Dorothy Norwood Starnes |

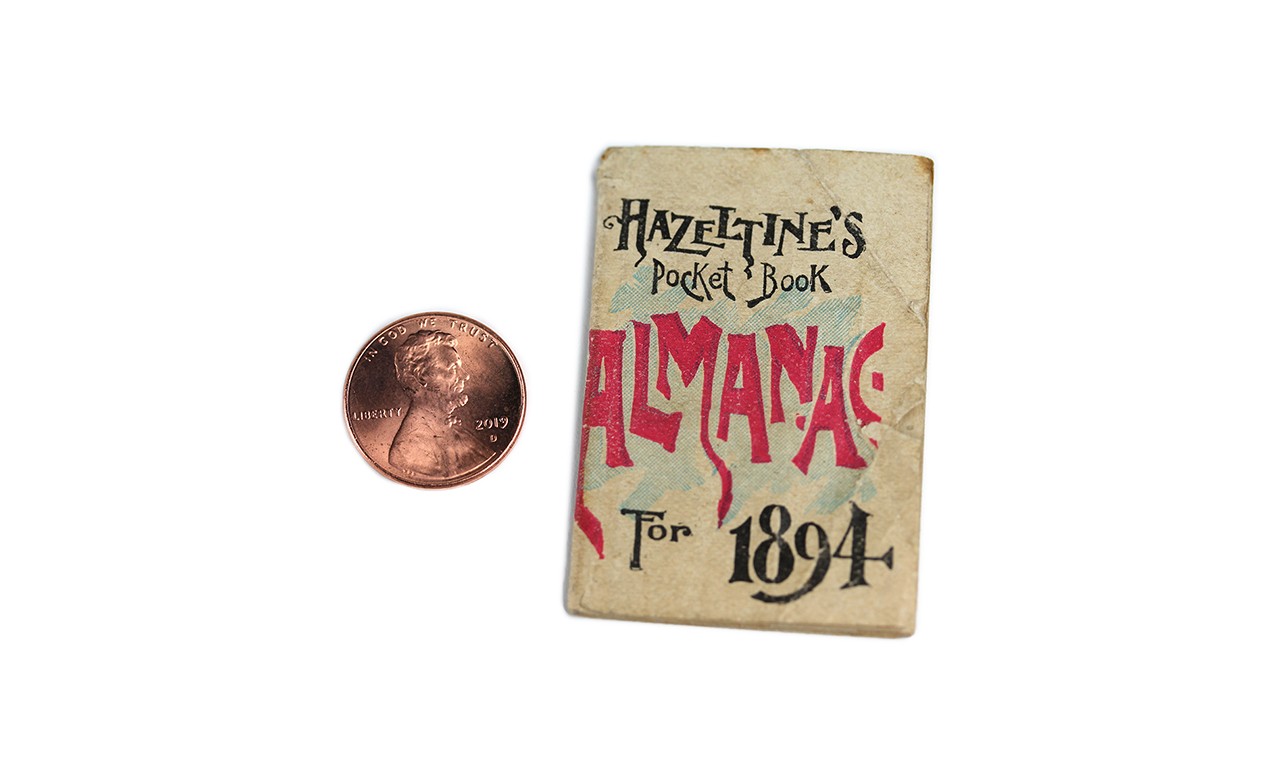

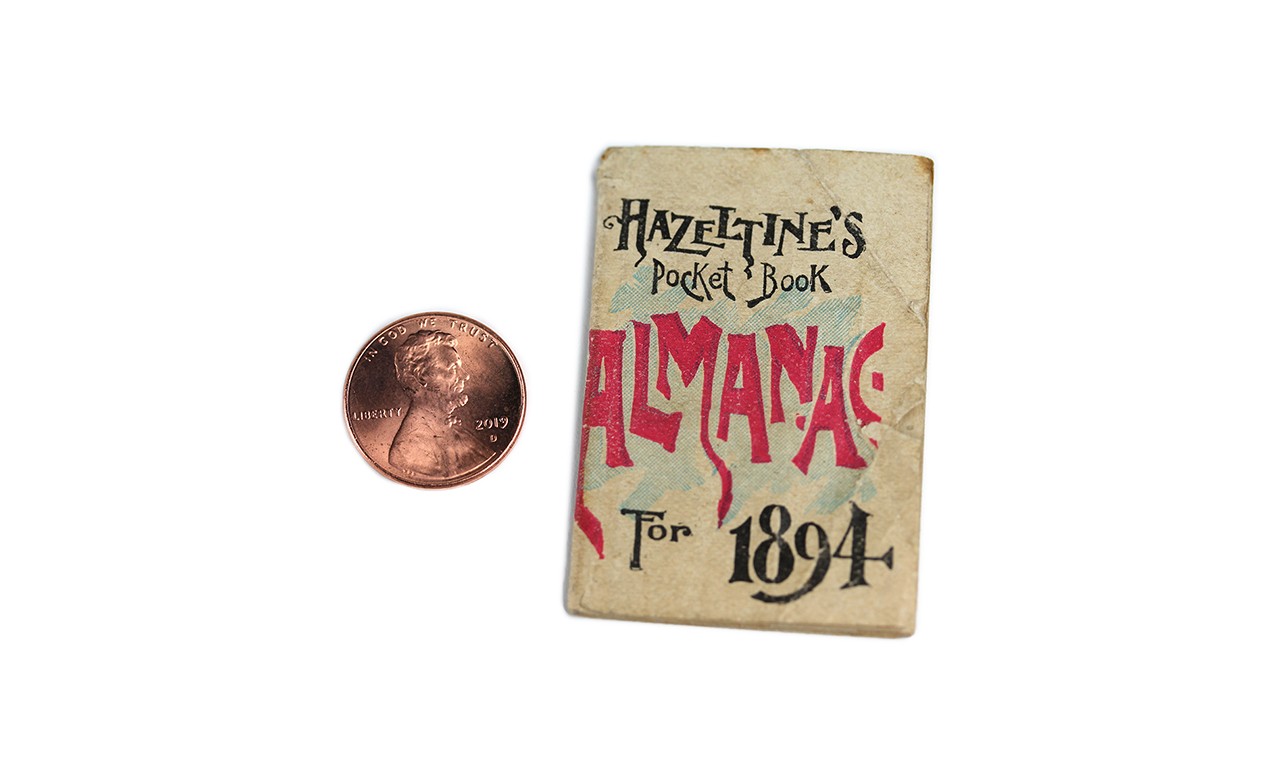

Hazeltine's Pocket book Almanac for 1894

E.T. Hazeltine; Warren, Pennsylvania

Leather and paper; 1 3/8 x 2 in.

40595.1

Gift of the Estate of Stella May Nau |

Fine Print

The origin of miniature books predates the turn of the 16th century. Often, the Bible and classics by renowned authors such as Shakespeare were printed in small format. These small publications served to be novelty and convenience items for travel. After the Industrial Revolution, miniature books were rapidly produced and as such lost a degree of the craftsmanship of previous publications. The ease of printing and novelty made publications such as this book from a six-volume set of Shakespeare’s complete works quite desirable. If you think the size of this book is small though, it is a goliath next to the Hazeltine’s Pocket Book Almanac for 1894, which is an impressively unimpressive 2 inches tall and still manages fully legible calendars and other readings. What better reminder that big things really can come in small packages?

Text and images may be under copyright. Please contact Collection Department for permission to use. Information subject to change upon further research.

Comments