|

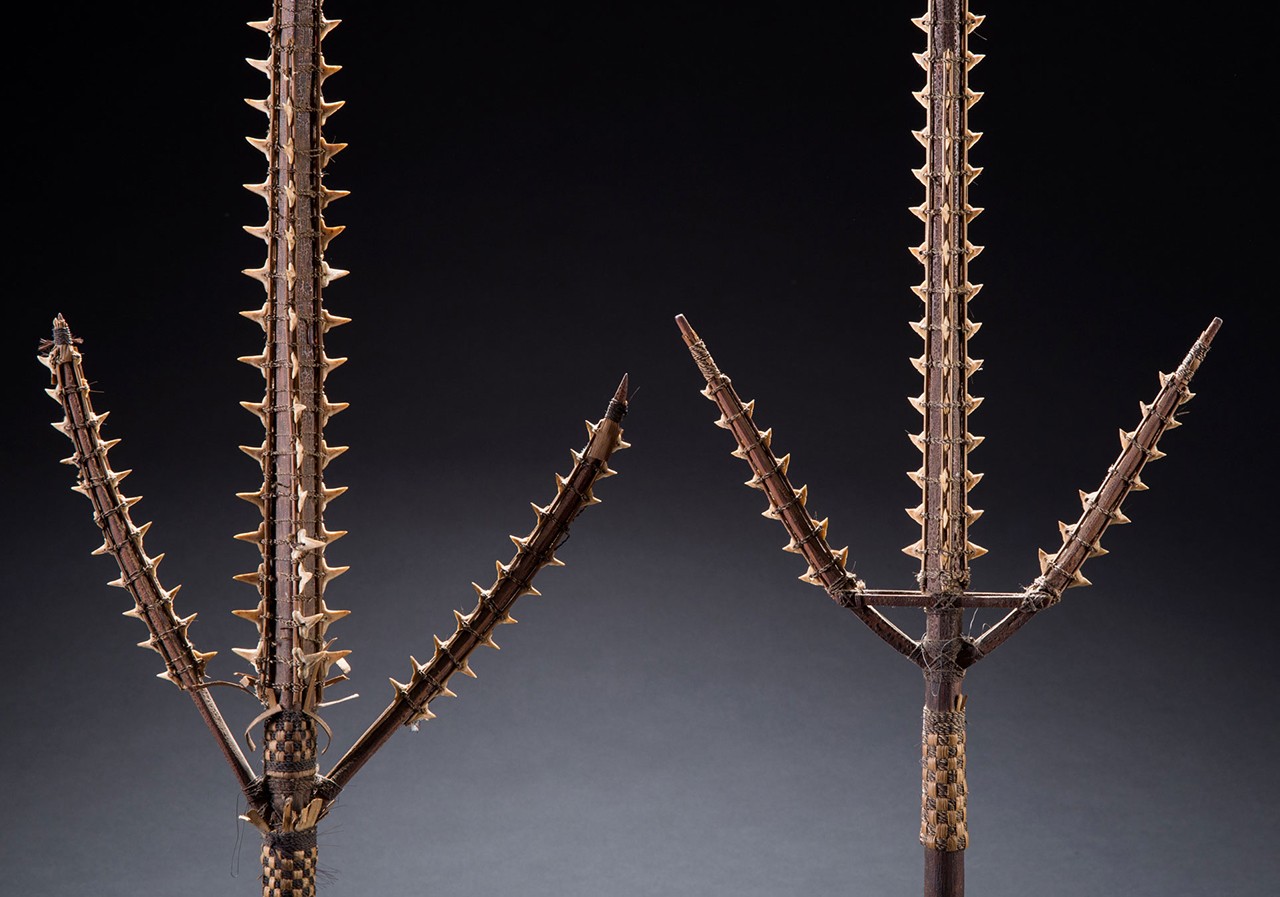

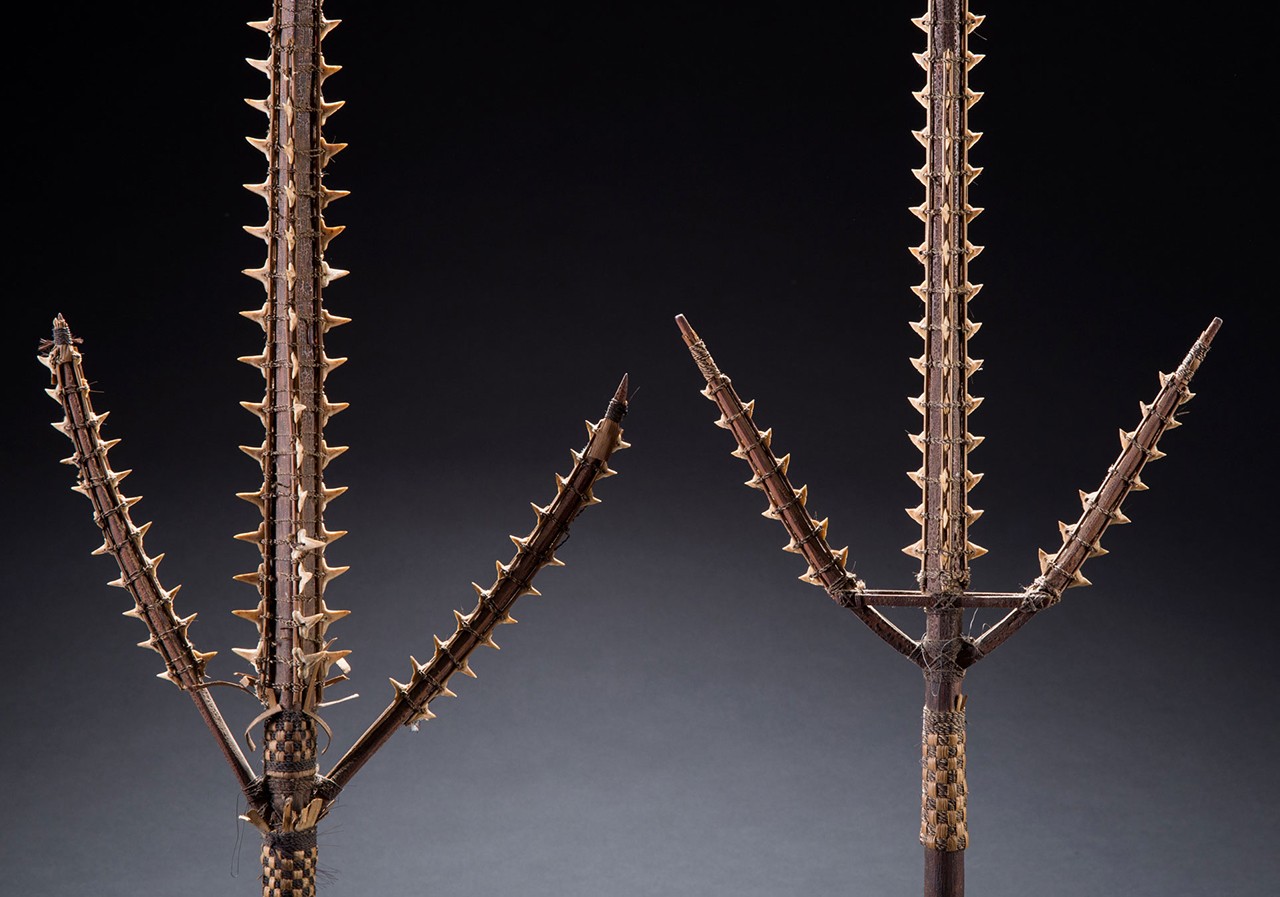

Spear Heads (Tataumanaria), late 19th Century

I-Kiribati culture; Gilbert Islands, Kiribati, Micronesia

Palm wood, shark teeth and sennit; various dimensions

2019.6.1-.2

Gift of Anne and Long Shung Shih |

Into the Maw

The Bowers Museum’s continued efforts to improve our Oceanic Collections has driven the acquisition of several shark tooth weapons from the Gilbert Islands within the past year. The first of these was a sword, followed by the acquisition of a woman’s knife in February. Two of the Bowers’ newest acquisitions, the subject of this blog post, are also Gilbertese shark tooth weapons; however, their identification is slightly more complicated than our previous Gilbert Island acquisitions. In today’s post we discuss the morphology and possible usage of these two newly acquired I-Kiribati weapons.

|

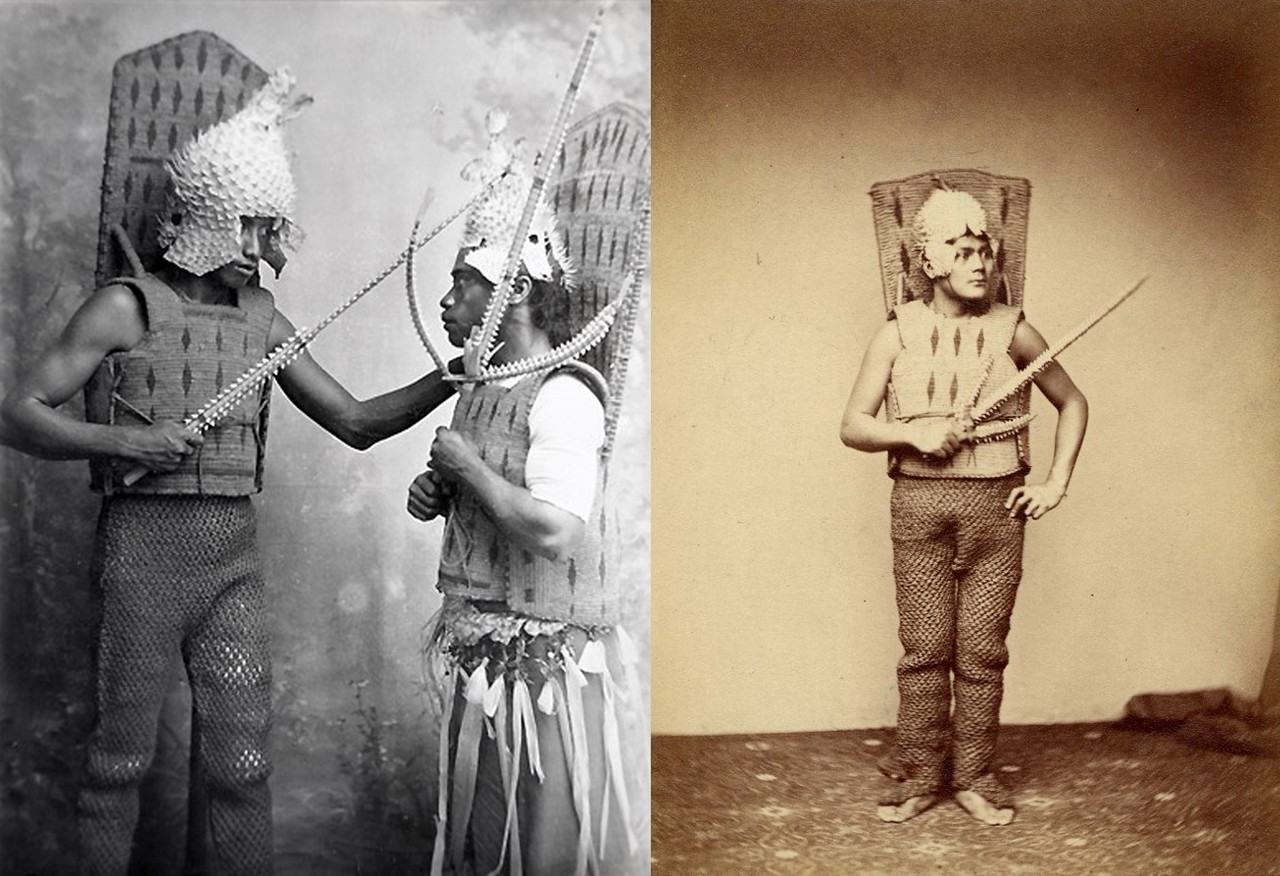

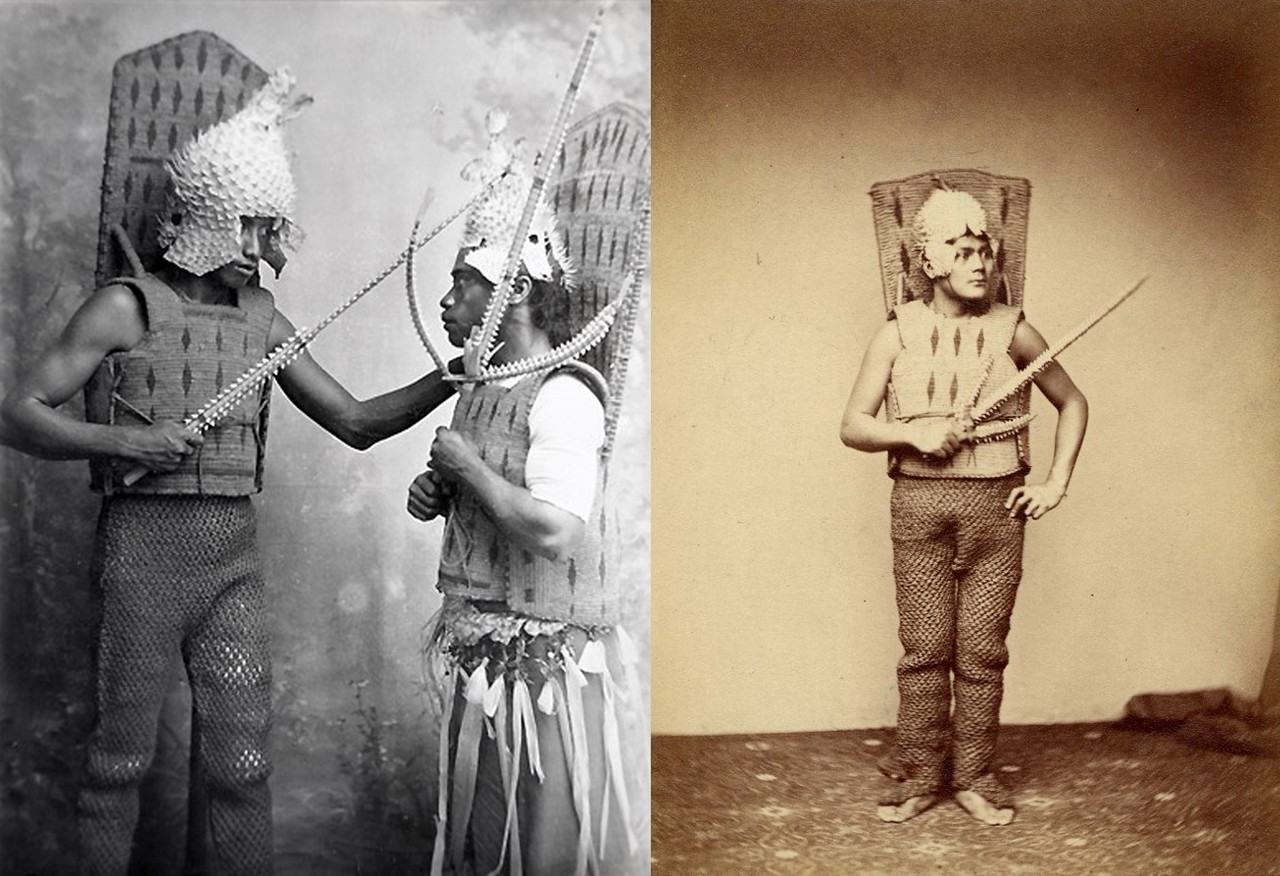

Two Men in Traditional I-Kiribati Armor

Museum of Archaeology & Anthropology |

Man in Traditional I-Kiribati Armor, 1863-1871

© The Trustees of the British Museum |

Be-coir or After?

Based on their size it would seem the weapons are swords, but the complicating factor in their identification is the presence of metal saw marks on the bottoms of both weapons. If these objects were originally spears separated from their longer, undecorated staffs then it might explain some of the inconsistencies with these weapons. As noted in our most recent post on the short blades of Kiribati, there are two excellent early studies of Gilbertese weaponry. Interestingly, neither includes a variant of pronged short sword like the two featured in this post, but both include longer spears with branches towards their heads. This is not to say that shorter shark tooth weapons with prongs were not used. Ethnographic images of Gilbertese warriors dating from the late 19th Century show men in full suits of coir armor with puffer fish helmets holding similarly pronged-swords. Examples in the British Museum and Smithsonian’s collections dating back to the 1860s also indicate that these pronged swords were used before Kiribati became a protectorate of England in 1892—the year which effectively marked the end of non-ceremonial I-Kiribati weaponry. One then, might believe that despite the saw marks these weapons are also swords, but there are a few other aesthetic variations which distinguish these objects. The first of these is that the base of Kiribati swords are often rounded, and even if they are not, they tend to narrow towards their lower terminus. The other factor is the prongs themselves.

|

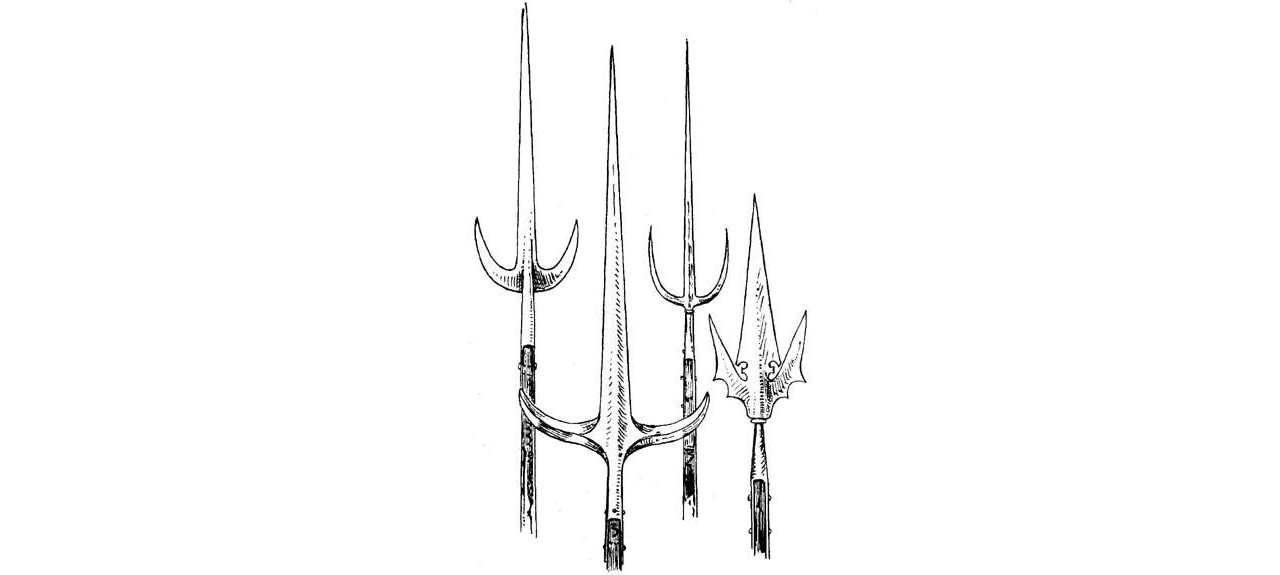

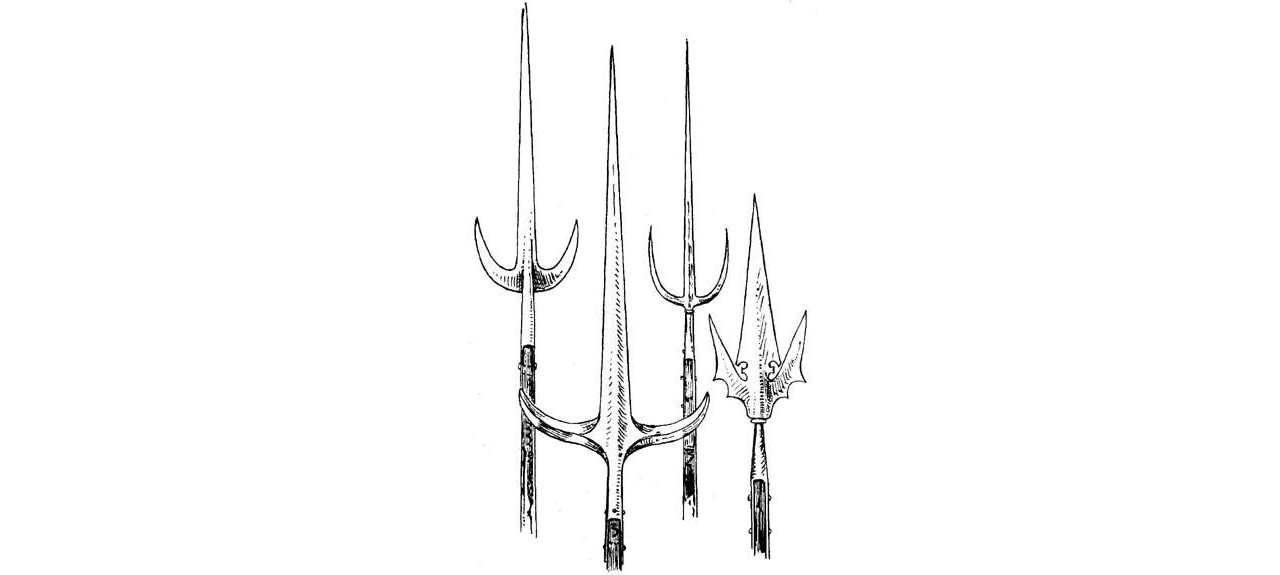

| Illustration from Handbuch der Waffenkunde. Das Waffenwesen in seiner historischen Entwicklung vom Beginn des Mittelalters bis zum Ende des 18 Jahrhunderts by W. Boeheim, Leipzig, 1890. |

For a Ranseur

While the toothed prongs held the potential to be every bit as dangerous as the primary shaft, their true benefit was the same as the steel partisans or ranseurs of Renaissance-era Europe: they were parrying weapons, highly effective at catching an opponent’s weapon and disarming them. Two methods were used to attach prongs. By far the most common was the use of two to four thick curved branches which were tied to the main shaft with fiber so that the butt of the prong extended a couple inches beyond its intersection with the shaft. The other style, employed in both these Gilbertese weapons, involved socketing two narrower prongs into the main shaft and again securing them with fiber. This latter method was almost exclusively employed with spear heads, while the former was used with both the pronged short swords and the prongs of long spears. Certainly not a decisive answer to the mystery, but while we continue to research these objects evidence seems to support that these weapons were originally spears, most likely referred to as tataumanaria or te mangau in the I-kiribati vernacular.

|

Spear Heads (Tataumanaria), late 19th Century

I-Kiribati culture; Gilbert Islands, Kiribati, Micronesia

Palm wood, shark teeth and sennit; various dimensions

2019.6.1-.2

Gift of Anne and Long Shung Shih |

Safe Distance

Swords and spears were generally used in unison in the traditional warfare of the Gilbert Islands. As noted in previous posts, battles can generally be described in several semi-regulated phases. The first round of combat between men of warring parties began with spearmen attacking one another. Spears were up to 18 feet in length, meaning that precisely wielding such weapons required immense strength. Damaging one’s opponent was further complicated by both the woven coir armor characteristic to the islands—it was sturdy enough that it effectively negated spear and sword blows, though depending on the suit there were still vulnerable spots at the joints, neck and face—and by most spearmen having attendants with shorter pronged spears similar to what we see in this post to defend them. I-Kiribati weapons tended to be extremely dangerous, but not particularly sturdy. Most times the switch from spears to swords was made when a spearman’s sword broke. Though swords were not intrinsically more dangerous than spears, the close range they forced caused them to be deadlier weapons.

Text and images may be under copyright. Please contact Collection Department for permission to use. References are available on request. Information subject to change upon further research.

Comments